Willie Williams – 5 Lessons in Light

Posted on December 2, 2025

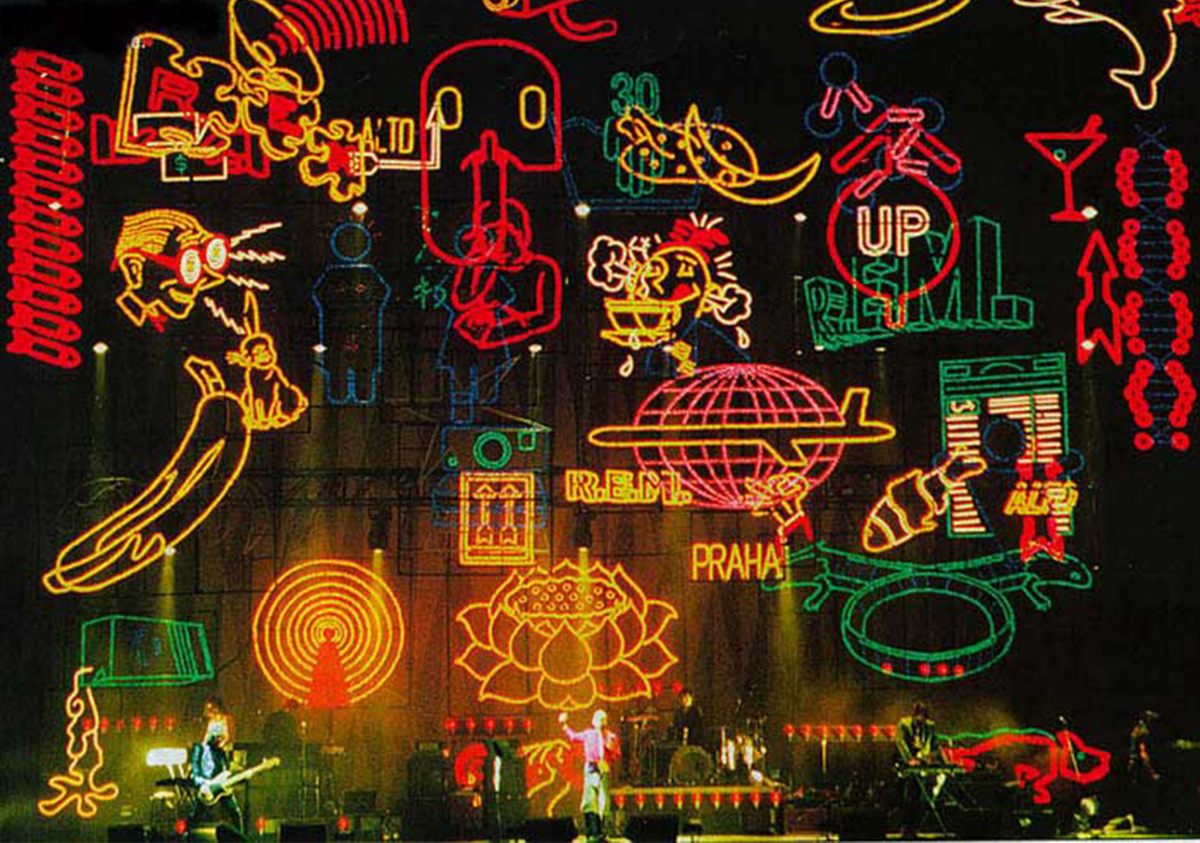

A show designer, director, and video-maker for concerts, theatre, and multimedia projects, this London-based designer is best known for his 40-year creative relationship with U2, whilst his work with George Michael, David Bowie and R.E.M. has also been celebrated for being both conceptually and technologically groundbreaking.

His performing arts projects include collaborations with Complicite, Kronos Quartet, and La La La Human Steps. In the world of theatre, his credits include video design for Prima Facie in the West End and on Broadway, for which he won a New York Drama Desk Award. His public works include lighting installations within Canterbury Cathedral, on London’s Southbank, and a permanent exhibit at Cleveland’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Museum.

Writing in Wired magazine, William Gibson noted, “Willie Williams combines a passionate delight in technology with an infectious low-tech joy. His innovations have become industry standards.” We’re grateful that he shared five invaluable lessons that he’s picked up along the way in his remarkable career.

One: Start With an Idea, not Equipment — I’m often teasing students presenting college work with the phrase, “that’s not a design, it’s an arrangement of equipment” (and let’s be honest, there are plenty of professional touring shows out there of which you could say the same). Much of the ‘design’ process now seems to consist of “getting a load of gear to production rehearsals (or a load of virtual gear into pre-viz) and seeing what looks you can get out of it; the notion of making design decisions in advance seems to have become quaintly old-fashioned. Moving fixtures, effects engines, media servers, ‘intelligent lighting’, LED screens; they’re all powerful and potentially wonderful tools but they are utterly promiscuous. Whatever they’ll do for you, they’ll do for anybody else with a half-decent programmer. Whether you’re illuminating a performance or creating a complete visual environment, if you start with the equipment list, you’ll immediately put a ceiling on how far you can go. If you start with a pencil, a blank page, and a cracking idea, then the sky’s the limit.

Two: Collaboration is key— Unless you’re creating a stand-alone installation, working with light is inevitably a process of collaboration. It’s important to understand the brief, whether you are there to illuminate a stage set, create an entire visual environment, or something in between. The most satisfying live shows work by tapping into multiple human senses simultaneously. Visuals are crucial, but so is sound, as are feelings and other elements that combine to provoke an emotional response. Viewing your colleagues from other departments as co-creators is vital, rather than ploughing a lone furrow and wondering why the show doesn’t hold together. Besides, nobody likes a showoff.

Three: Less Is More — This might sound ridiculous coming from me, but even when designing shows that are vast in scale, I always find great satisfaction in making it all work with the fewest ingredients possible. If I can distil a show down to one primary idea or one object, so much the better. I love the stance of creating bold, strong scenes and letting the audience look at them without endlessly meddling. It’s easy to think that if the lights aren’t ‘doing something’ then the audience will get bored or the energy will drop. With the right performer, though, a strong look can sustain for far longer than you might imagine. The flipside of this is that every change you do make then feels more intentional and so delivers a lot more power. I still have to remind myself of this on occasion and have even been known to stick a piece of tape on the console marked “Leave It Alone”.

Four: Save Some Ammunition — Great big effects become exponentially less memorable the more frequently they are used, so pace yourself. My director friend, Simon McBurney, has a wonderful observation about the end of a show: “They will judge you on your dismount”. In short, no matter how extraordinary a performance might be, without a payoff strategy, you can still leave an audience feeling unsatisfied. I’ve discovered that this advice applies to many situations in life (and possibly even to life itself), but certainly it’s worth considering for lighting a show. No matter how much or how little you have in your arsenal, it’s well worth keeping a little under wraps, so you have something new to show the audience before sending them home.

Five: Love what you do — It’s a great privilege to work with the intangible yet disproportionately influential medium that is light. Lighting is everything; we control the mood, the energy, and we decide what the viewer gets to see or not see. We get to create an atmosphere that can’t be felt secondhand; you have to be there to experience it. The other side of this coin is how frustratingly impermanent our craft is. When the curtain comes down or when the tour is over, you are left with absolutely nothing to show for it apart from another laminate to hang on the back of the bathroom door. There’s no way to recreate the work or the experience in isolation; it existed for a period of time, and now it’s gone forever. It bears a parallel to the world of dance. The great choreographer Merce Cunningham put it, “You have to love dancing to stick to it. It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed & sold, nothing but that single, fleeting moment when you feel alive.” It’s a great lesson to appreciate every show at the time, to remember to be in the moment, and to love what you do.