Willie Williams Counterpoised Light

Posted on December 5, 2023

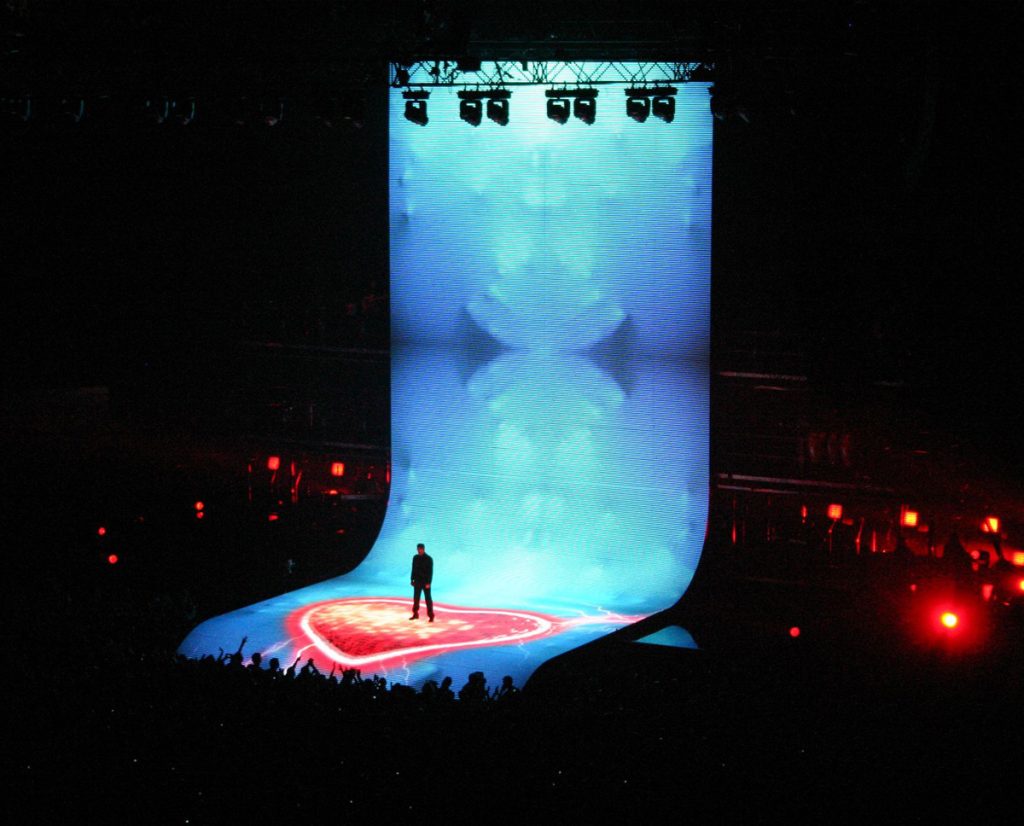

Minimalism can exert its power in the most unlikely places, even at the U2 UV Achtung Baby Live show that opened the much-heralded Sphere in Las Vegas this September. Although the show at the massive structure with a 16k resolution wrap around video wall, enraptured audiences with its immersive and complex design, at its heart was a single, basic “thought-line” that ran through it from beginning to end.

Willie Williams would have it no other way. A self-described minimalist, the London-based designer led the Treatment Studio team responsible for the massive production. While it might seem contradictory that someone dedicated to pursuing an uncluttered approach to design could create such a complex show, Williams sees no such contradiction. To him it is the job of designers to build a show around their creative vision, not the technology at their disposal.

A piece of equipment is not an idea; it is intended to serve creativity not replace it, as Williams likes to say. If it were any other way, then how could design avoid falling into a bland state on mediocre homogeneity?

Admittedly, maintaining the dominance of creativity over technology has become more challenging given the powerful, sophisticated tools available to designers today, but this is where the importance of counterpoising vision over gear becomes most important. Steeling oneself and not relying on tools to do it all in a design, is the only way to find a balance between spectacle and intimacy; between blowing minds and connecting with souls, in Williams’ view.

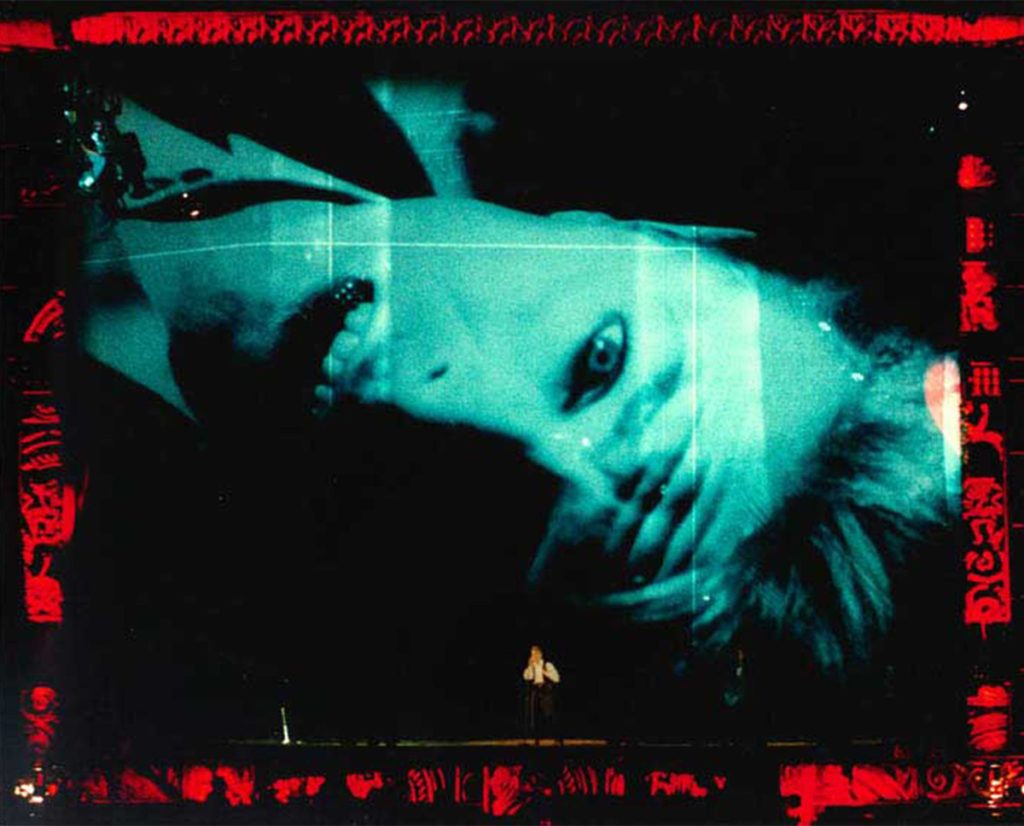

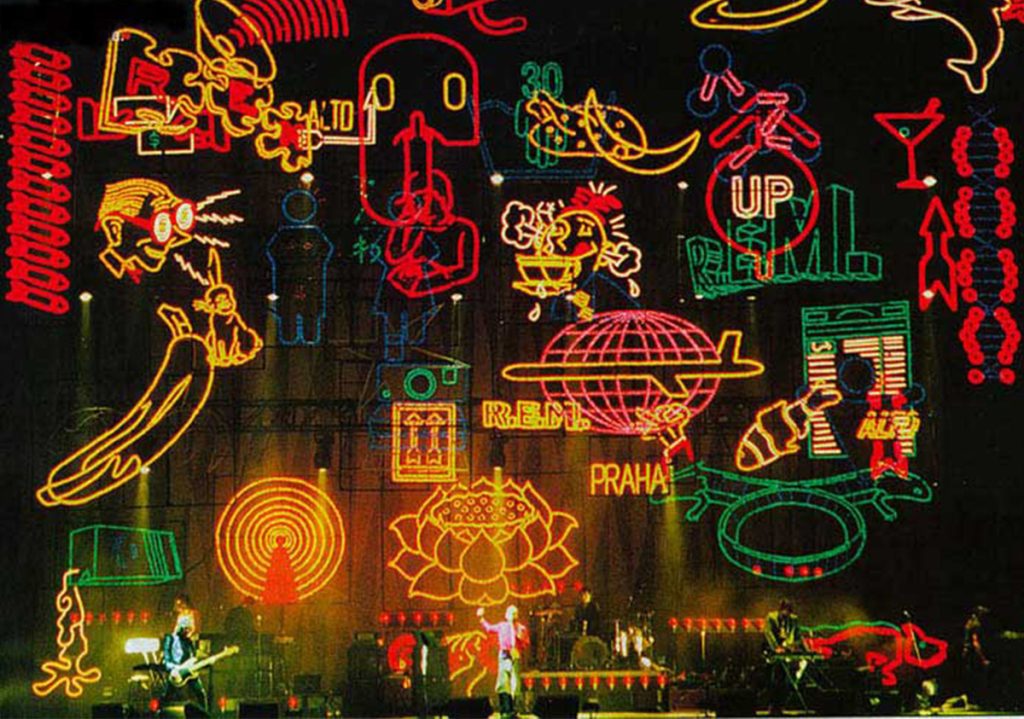

Mastering this balance, Williams has created looks that are spectacularly powerful, while still remaining emotional and intimate He’s done this not only for longtime client U2, but also other artists, such as David Bowie, R.E.M. and George Michael. Returning from Las Vegas to his studio in London, he spoke to us about the power of balance in design.

We were intrigued by the name, Treatment Studio. Can you tell us how it came about and what it represents in terms of your approach to your work?

“The name was from my partner in the studio, Sam Pattinson. Sam and I are both a little publicity shy, preferring to let the work speak for itself. Consequently, the name was originally styled as ‘(TREATMENT),’ in parentheses because we always felt that our presence in a project was peripheral to the main event, which was the performer.”

You’ve said that when designing U2’s show for Sphere, you were concerned that hardware, rather than a concept, could serve as the springboard for a design. Given how design tools have become so much more powerful and complex, do you think we’ll see more instances where hardware or some other form of technology serves as the initial impetus for a design? How do you feel the growing importance of these tools will influence the creative process for designers?

“Whenever I speak to young designers or students, I am always keen to get across that the current emphasis on shows being so tech-led can often be more of an obstacle than an aid to creativity. A piece of equipment is not an idea, so the gear should always serve the creativity rather than being the creativity. The question to ask is what am I bringing to this design that is uniquely my own? Rather than what will this piece of equipment do?

“At the dawn of concert touring, equipment was almost entirely borrowed from theatre world, and was often so primitive that it was completely normal to have to invent whatever you might need to bring an adventurous vision to life. When moving lights first began to appear in the early ‘80s, on one level it was very exciting, because the potential was so enormous. It was shocking, however, to note how quickly the look of touring shows began to become homogenized. This was shocking, though perhaps unsurprising, given that there was just a handful of designers using these same products to design 90% of the big touring shows.

“Much as I have always been intrigued by technology, I soon developed a healthy skepticism towards moving lights — perhaps because initially I didn’t have any clients who could afford them. This skepticism stayed with me as time went on and became vital to my process, always pushing me to look at ideas in a different way or to find alternatives to the obvious. As an example, during this time I became fascinated by human-operated, truss-mounted follow spots which struck me as being a completely organic kind of moving light. Given the human factor, the motion of each one was slightly different and unpredictable, so they looked wonderful in large numbers. As budgets grew, I confess I might have gone slightly overboard, peaking at 25 truss spots on U2’s 1987 Joshua Tree tour, but it’s safe to say there was nothing else out there at the time that looked remotely like it.”

Can you talk about how LED videos relate to this development?

“The current ubiquity of LED video screens has taken this homogenization to an extreme. A ‘design’ now can frequently be little more than an arrangement of equipment and ‘programming,’ which is often little more than a process of scrolling through menus to find what might look good in situ. Similarly, you have media servers producing, what even its creators have been known to refer to as ‘splodge.’”

So, how do you asses the balance of technology and creativity?

“At this juncture, there are very pertinent questions to be asked as to wherein lies the act of creativity, and a strong case to be argued that far more of the genuine creativity lies with the equipment manufacturers than with its users. Given that equipment fabrication is very much a for-profit industry, it seems legitimate to question the place of art within that process.

“That said, of course, it remains perfectly possible to realize an original, artistic vision utilizing pre-existing equipment, but that vision has to be clear prior to the drawing up of an equipment list. The gear isn’t going to do it for you; and indeed, it can often get in the way — don’t get me started on effects engines. The long nights I’ve spent trying to get digital strobes to resemble anything like actual strobe lights have been enough to make me yearn nostalgically for a pin matrix.

“Consequently, the Sphere gave me pause for thought because it broke my cardinal rule about the starting point of a design. The Sphere’s auditorium is a vast video screen that obliterates everything else, including anywhere useful to hang scenery or lighting. So, clearly, I was going to have to take this on in a way that would be untraditional for me. Maybe this ended up being a good thing, pushing me out of my comfort zone in a different way. I wasn’t going to be able to approach the Sphere in the same manner that I’d approached anything before.”

There were so many stunning and beautiful moments during U2s show at the sphere, yet you were careful to have what you described as a “thought line” run through the production. Howwould you describe that thought line?

“It seemed clear that the possibility of overwhelming the audience was very real. Much of my adult life has been given to figuring out how to combine human-sized performers with outsized images, but here the balance of power seemed far more skewed than anything we’ve seen before. To keep an audience engaged, it is vital to find a balance between spectacle and intimacy; between blowing minds and connecting with souls. I joke about being drawn to ‘minimalism,’ given the scale of some of the shows I’ve made, but I always try to pare a design down to a single idea, a single object, a single thought, from which everything else emerges.

“Perhaps a better word would be ‘restraint.’ No matter how visually extraordinary a show is, the performer absolutely has to appear to be in control of everything that we’re hearing and seeing, otherwise the whole enterprise falls into hollow spectacle that ultimately leaves the audience with nothing.

“Some of the U2 shows that we’ve made have contained a tangible narrative, whereas the Sphere show is more about a coherent visual through-line. I don’t often go in all-guns-blazing at the top of a show — restraint and all that, but given the hype about this building I figured it made sense to do exactly that. For the first 40 minutes we pretty much drive an audio-visual tank over the audience — and enormous fun it is too. This part of the show draws on the aesthetic of the ZooTV tour, but taken to a level we couldn’t have dreamed of in 1992. Having got this out of our system, we then pretty much turn the screen off for the whole second act of the show before returning for the final section where we use full-screen cinematic imagery, more akin to what the building was designed for.”

Along those lines, it was very impressive how you changed looks during the U2 show, moving between soft looks and bold ones, realistic imagery and fantastical scenes. Were there any looks that you liked that wound up having to be left out of the show at The Sphere?

“From the very beginning I was clear with the band that we were building an ocean liner not a dingy, so changing course quickly would not be possible. They absolutely took this on board and were involved in the whole design journey, which was fantastically helpful. Looking back through the archive, I was amazed to find a storyboard from about March this year which is pretty much the show we delivered in September.

“The only things that really didn’t work were when we tried to take on the physicality of the venue. The room doesn’t feel too enormous when you’re inside it, in fact it’s weirdly intimate; essentially an amphitheater with an oversized roof. However, attempting to fill this void with physical scenery only served to show how vast the airspace really is. I had notions of hanging fabric or hoisting scenic elements to get us away from the virtual, but it soon became apparent that this would be a fool’s errand.

“Video-wise the space proved to be a little more forgiving than I’d imagined. There are only a couple of sequences that might make the viewer feel a little seasick, though sadly I did have to let go of the idea of the entire screen strobing through colours at high speed.”

Looking beyond The Sphere, you worked with David Bowie on The Tin Machine Tour. What was that like? How did that influence your development as a designer?

“I got to work with God for three years which is as good as internships get. Better yet, I got to do the two Tin Machine tours, in tiny clubs, plus the Sound + Vision stadium tour with its huge film projection, whilst the man himself performed every song you could ever hope to hear.

“I think my main takeaway from David Bowie was creative courage. He was at a point in his career when truly he couldn’t give a damn about what anyone said, especially with Tin Machine. As a result, he encouraged me to take my instinct for minimalism to its extreme. I came to understand that with a great performance, if you are presenting a strong, bold visual, it will really sustain and that you can trust the audience to go with it. ‘Less’ really was ‘more’ on that tour, with maybe just five or six lighting looks and, on average, probably less than one cue per song. I absolutely loved it, but it was hard to avoid itchy fingers at first. So much so, I wrote a note on a piece of electrical tape and stuck it on the lighting console: ‘Leave It Alone.’”

Looking at lighting in general, its role in productions seems to have changed quite significantly as immersive 3D video elements have become more central to design. It seems that in many cases lighting has gone from a central to a supporting role. How do you asses this change? How do you view lighting’s new role? Have the changes we just mentioned created a demand for new, or different, kinds of lighting fixtures?

“For me it has always been impossible to separate lighting from video. When these are designed by two different people it can often lead to a kind of star wars situation where there are two voices trying to shout over one another. This probably explains why so many new generation lighting fixtures look more like weapons of mass destruction than something that might genuinely be useful in the lighting of a stage. EDM festivals and K-Pop concerts are likely the most extreme versions of this– and in truth there is something exhilarating about that degree of abandonment of restraint in the service of spectacle, but both have long let go of the notion of attempting to enhance a musician’s performance in any meaningful way.”

Creating the kinds of powerful all-encompassing shows that you do, how do you ensure that the attention is always focused on the artist on stage?

“The most important element of designing a show is my creative relationship with the performer. It requires a great deal of trust for a performer to be comfortable enough to let go of the reins and be temporarily subsumed into the visual environment. They have to be confident that I will keep bringing focus back to them and that when the audience leaves the show, the lasting memory will be of the performer; that somehow the sound and all the visuals were at their service, rather than being a separate entity.”

Do you ever find yourself wanting to light a simple show with a few washes and batten in the background?

“Happily, I still do. Bono’s Surrender one-man show earlier in the year was very minimal and clients like Kronos Quartet & Laurie Anderson produce wonderfully fulfilling shows with very little equipment, such is the way of the ‘performing arts’ world. I work with an extraordinarily talented British performer called ‘Self Esteem’ whom I have helped as she made her way from tiny clubs to Hammersmith Apollo (and will no doubt go far further yet). The last show I did before the pandemic was U2 playing a football stadium in Mumbai in India. My first show after the pandemic was Self Esteem in a room above a pub in Huddersfield, with 12 lights that I drove to the gig myself in the trunk of my own car. The variety is what keeps me interested.”

What do you thing you would have done if you didn’t become a designer?

“I was supposed to study Physics at University College London but punk rock staged an intervention and I dropped out shortly before I was due to start. It was a fantastically fertile time in the UK and the message in the air was ‘anybody can do anything.’ There was a new band appearing every five minutes, so I put my education on hold — indefinitely, turns out, in order to be part of what was going on. Visual things were more appealing to me than sonic things, so I started playing with props and lights for a whole slew of bands who didn’t get anywhere, before eventually finding some bands that did.”

What is the one thing you want people to know about you as a designer?

“I do all my own stunts.”