Seth Bernstein – Contextual Light

Posted on February 4, 2025

Unless you happen to be a crossword puzzle devotee you might not be familiar with the word “ethnography,” but it’s one that any LD would do well to consider. At least that’s a lesson that can be gleaned from the richly varied and successful career of this New York and Los Angeles-based designer.

A psychology and anthropology major in college, Seth Bernstein has wholeheartedly embraced the concept of ethnography, which Websters defines as the study and systematic recordings of human cultures. It is by viewing his work through this inquisitive and empathetic prism, that he ultimately gains a deeper understanding of how it will be viewed by others.

Approaching each project as if it were a journey into new, uncharted territory, Bernstein digs deep into every background detail of the work at hand. His delving is never limited to the usual parameters such as stage size, trim heights, budget and the like, but also extends to more amorphous cultural qualities that will ultimately define the context of the environment surrounding his work.

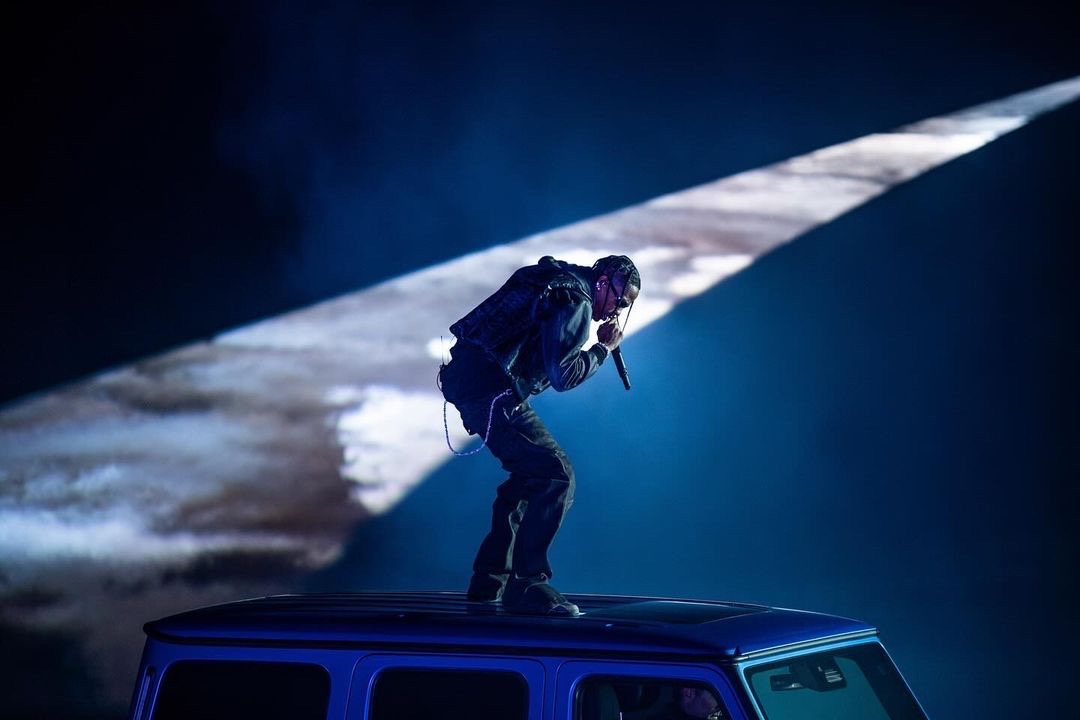

Following this approach, Bernstein has left his mark on an extraordinarily wide range of high profile projects, including TV programs like Late Night with Seth Meyers and Saturday Night Live, fashion shows for Victoria’s Secret and Chanel, the Mercedes-Benz G-Series unveil with Travis Scott, Post Malone’s 2024-25 tour, the annual Puppy Bowl, and many others.

Although these and other projects often take place in very different and sometimes unusual, settings (such as a stage set up in the middle of a lake!), all are infused with a sense of authenticity that reflects their specific framework – the result, no doubt, of this designer commitment understanding the world his work resides in.

Taking time from his busy schedule, Bernstein talked to us about the power of contextual light.

We understand you majored in psychology and anthropology at Brandeis. Has this influenced your approach to lighting design?

“Yes, it’s true… and I picked those majors knowing I wanted to be a lighting designer too! For me, the part of my education that stuck was the concept of an ethnography. Where you go someplace new and try to unpack another culture’s worldview… reason out how they think and why. For me, when I start a show, I try to run a quick ethnography of the artist, brand, etc. What’s the world they live in? What’s considered ‘sacred,’ and what can be changed? That’s what stuck with me.”

So, we have to ask also — what is the most import psychological quality a lighting designer should have?

“I’d say resilience! Projects move so fast you need to be constantly recovering from small slights, interpersonal conflict, or a big failure or error — yes, they happen.”

For the Mercedes-Benz G-Class unveil event you had to light a platform that appeared to be floating in a lake. You also lit a temporary basketball court outside Lincoln Center for the World Basketball Festival. You’ve often created designs in such out-of-the ordinary places. Can you give us an idea of how you are able to achieve your vision as a lighting designer, while still accommodating the “realities” of these unusual settings?

“I think it’s been a feedback loop where I execute a show under crazy circumstances which puts me on the radar for more. For me, it’s an exercise in priorities.”

What is the one facet of the design that you’re going to preserve at all costs?

“For Lincoln Center, I wanted the lighting pods to be perfect. Perfectly level, fixtures perfectly aligned, placement perfect so they looked like a Met Opera set piece that fit into the environment, instead of the industrial behemoth that they were. For the lake stage I really wanted the lighting to fully wrap around the entire shoreline so we could achieve these saturated colors that would send the whole horizon into an ethereal place that we could break with the lasers. When we couldn’t build any high positions due to budget and soil conditions, I had to bike back to site many times to scout where we could slip things in to natural high ground and clearings.”

The Mercedes event featured a performance by Travis Scott, during which you made excellent use of shadows and dark space. To us that really made it seem like a concert performance. Do you put on a different creative hat when you light the entertainment part of the event than you do the actual event itself?

“No, that’s what makes the work we’ve been doing special. We really try to find a scheme that works for both the artist and the brand in a way where nothing is compromised. And we’ve been very successful in that.”

On the subject of live performances, you recently did a tour and Nashville Stadium show with Post Malone. What were the big differences lighting live music on a tour as opposed to an event?

“This was a very unique case where I was working with Creative Director and Stage Designer Lewis James on a tour centered around music no one had ever heard –including us! Also, they were planning on playing a mix of amphitheaters and Stadiums… so it was the opposite of the specificity I normally work with!”

“The exciting part was merging the references Lewis has been using for Post with some key vibes we liked from the world of country music; then watching the whole thing come together once we finally heard the music and saw the band onstage. We also purposefully set the whole thing up to be adaptable. With manually operated fixtures atop scaffolding on stage and a show file that could easily switch back and forth between timecode and live operation.”

When you are asked to design an event, what are the first things you look at regarding the space where it is to be held?

“I would say the first thing I look at is limitations that might end up being inspirational. If there’s a huge skylight, how can we use it instead of blacking it out? I also try to imagine the crew loading a rig into the space. Time is always tight these days – so what elements should be immediately taken off the table because they’ll just end up being too cumbersome and prevent us from getting the time we need to actually focus and program.”

You do the lighting design for the Puppy Bowl that coincides with the Super Bowl. What is that like? Are there any big challenges working with all those dogs?

“I’ve been lighting this show for six years and was part of taking it from tungsten to LED panels and automated fixtures. In recent years, it’s been extremely rewarding because the new fixtures allow the field to run much cooler, which was much more conducive to high energy from the dogs on the field… and it also resulted in a happier handling team. There are quite a few folks just off camera wrangling all the dogs! Also, the new fixtures were softer, which allowed the jib camera to get way closer for great shots without casting any shadows. That was also a huge win for the broadcast that I’m very proud of.”

We were very impressed with the work you did lighting Reneé Rapp on Saturday Night Live, particularly how you maintained such steady key lighting while also doing some heavy strobing. What was the key to that?

“Thank you! SNL divides the music and key lighting between different programmers — so you can have two sets of eyes monitoring each facet… which is key in a live context. For that performance we used the same turntable for both songs and the studio crew was generous enough to move it between two marks during commercial breaks. That was the only way we could get the necessary depth to get both steady key light and a dynamic background for the different choreography/scenography of both songs.”

You do quite a bit of other television lighting, including for Seth Meyers. What are the biggest challenges there compared to event lighting?

“The main difference is always time. TV sets and studios are scheduled very tightly so we have to pull everything off in a very limited window before they need to move on to other segments. Pre-production and decisive thinking are always the key to this.”

Another TV project you did was Dead Funny, a Joan Rivers Tribute. What was that like?

“This was another example of a very tight timeframe. We partially loaded in the show and then had to clean up and open the house for Amateur Night at The Apollo (a totally different production that needed a clear stage.) Then, we came back at 12:01AM and had roughly 18 hours to load in, focus and rehearse the special before the audience loaded in. This was an exercise in rapid collaboration with production designer Tom Lenz and director Carrie Havel, but we all got through it!”

You’ve also done some excellent work in fashion shows like Victoria’s Secret on Amazon Live with Tom Sutherland, as well as H&M events. How do those projects differ from concerts and corporate events?

“Fashion Shows are very interesting because you have to consider the clothes and talent key lighting much more closely than a typical TV or concert environment. Also, the model walks for these big shows are typically long… and getting an even field of light for that kind of area is very difficult but absolutely critical for the project.”

“Regarding the Victoria’s Secret show, it was great to be paired up with Tom Sutherland, because my team could really focus on the key lighting while they worked on the music acts. Then we came together on the transitions and overlaps, always checking in with each other. It was a great collaboration with Tom. I think we made some new kinds of magic on this show.”

You did some excellent work for the Disney 100 exhibition, which relied heavily on bold colors. Do you have any go to colors? Any colors that you prefer to stay away from?

“I don’t often get to use color like this, so an exhibition is a great way to try new things. Typically ,we try to avoid super saturated blues but this was one moment where we could really lean into that. I would say that the world of acceptable colors has opened wider in fact. Green used to be avoided at all cost but I now find myself using it often.”

Throughout much of your work, you use sihillouetes often accompanied by fog. What do you think sihillouetes bring to a design? What does fog add to the effect of sihillouetes?

“Fog is really important for my designs, but also something to be treated with extreme caution. The wrong wind direction or too heavy a hand on the controller and the entire moment can be lost for the cameras and audience. We always do extensive testing as part of rehearsals and see how far we can push it… because the silhouettes can always be quite magical. For a recent show at the TSX stage in Times Square I devoted myself entirely to controlling the fog and Lighting Director Harry Forster took on everything else… because it was that critical and the right level was always on the razors edge.”

In general terms, how do you get your creative juices flowing at the start of a project? Long walks? Listening to music. What is it that sets you in the right frame of mind creatively?

“I’m a huge proponent of using “brain idle time” to let ideas come naturally. I never force myself to come up with a solution while “on the clock” and sitting at my desk. This is not to say I don’t do my homework… instead I take my office time to memorize all aspects of the project, study all the variables and then take the time away to let it process in the background until the idea comes. Usually this happens while cooking, riding my bike or some other non-work context. Also, while traveling for work (which I do often) I try to see the local museum, walk the architecture or find a park. This always helps open up the circumstances for a random discovery that saves the day at some point.”

Do you ever procrastinate at the start of a project?’

“Always! I highly recommend not punishing yourself for procrastination. I really think great ideas only come in their own time.”

Why did you become a designer?

“I always wanted to do this, from a very young age. I was always attracted to the practicality of it — taking a kit of parts and making it into something special. It started with my Legos and then built into stadiums, sound stages, semi-trucks full of gear and huge teams making it happen. I’m deeply grateful to everyone who has ever taken a chance on me and the crews who show up every day and night to build the shows.”

What would you have done if you didn’t become a designer?

“I think I was always meant to be a designer… so I’ll answer a different question. What would I design if not lighting? I’m getting really interested in cars, which is ironic because everyone who knows me knows I ride a bicycle everywhere. As an object they’re so complex and intricate. If I were to be reborn or have a second career it would involve creative direction in the automotive field.”

What is the one thing you want people to know about you as a designer?

“I want people to know that I’m a collaborator to the core. I’m always willing to put in the work and “meet someone where they are” if we get paired up or choose to work with me.”