Nico Riot Purposeful Light

Posted on October 4, 2022

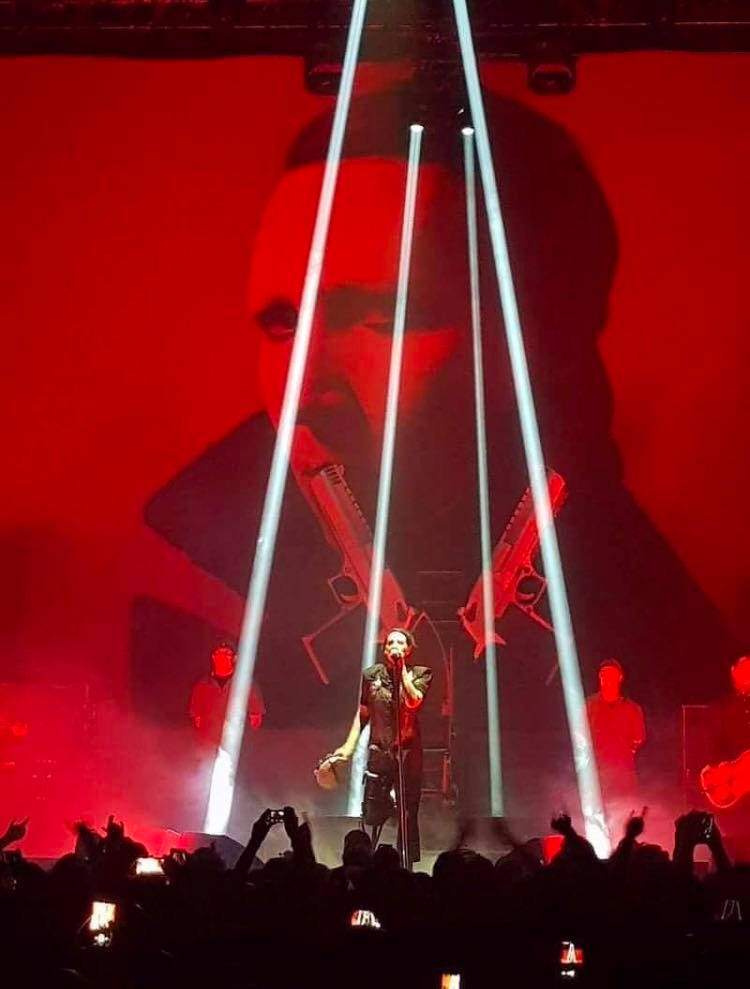

Art is the elimination of the unnecessary, Picasso once observed. Although the great artist never tried his hand at lighting design, (imagine what he would have done with color mixing LEDs!), his words aptly describe the philosophy that this French designer has followed when lighting shows for clients like Marilyn Manson, GOJIRA, and the 2021 Grammy winning band The Strokes.

Casting aside, what he regards as unnecessary frills, Riot focuses relentlessly on the core elements of lighting design. What better way to reflect the power of an artist’s music than by unleashing the purest form of intensity one can create without distractions, using stark color combinations, defiant light angles, bright strobing, and ominous atmospherics?

Although a disruptive element may run through some of Riot’s shows, they are far from blindly chaotic. On the contrary, they’re carefully and intricately planned down to the smallest detail to fulfill what he regards as their primary mission, which is to create visuals that reflect a clients’ music.

A lighting design should never stray too far from the music that is its raison d’etre, believes Riot, who recalls a lesson from earlier in his career when a client drummer taught him time signature so his strobing could be in perfect sync with each song’s percussive tracks. This kind of collaboration embodies much of what he values most being a designer.

Speaking to us from his studio in France, Riot shared insights into the power of purposeful design.

At Chirac Design, you tend to have intense, some might say irreverent clients like Marilyn Manson and Ultra Vomit. Yet you yourself are always easy going and friendly. What is it about these bands that make them a good fit creatively for you?

“Maybe it’s because we understand this kind of music and we are all pretty open minded. I come from the metal scene and almost everyone in Chirac is a musician playing in underground rock scenes. That might help a bit. We also don’t take ourself too seriously either.”

Your lighting maintains a constantly high level of intensity for these bands. How do you manage that?

“I don’t know. I think it is because the intensity of the music is always calling for it. There is something really addictive when the light and the sound come together to deliver a huge visual and sonic deflagration. If a song starts already on a fast and strobing note, you need to have more in reserve to match the intensity of the track.”

Would you describe these looks as “angry lighting?”

“Not necessarily; it might be looking intense, but it’s never for no reason. I hope it’s always justifiable intensity anyway. I tend to program with minimal looks, not so much movements, no gobos or FX tricks. All the energy is directed towards the music to match the intensity. It’s all about timing – getting the right hits or light blasts at the right time.”

Recently, you began working for Grammy winners The Strokes. Their indie-garage band sound is quite different from the kind of music many of your other clients play. How is this reflected in your design?

“This was a codesign with my dear friend, Pierre Claude. We were looking for something simple, but something also that when you look closely, it becomes a bit more intricate than it seems at first glance. Pierre and I designed and programmed together. I learned a lot from him. You were talking about intense lighting – well, he definitely goes harder than I do ha ha! I really loved the creative process. Pierre is working with a less- is-more philosophy. Simple but tight. We realized we are coming from different backgrounds — electro for him, rock metal for me — but we have the same approach and love the same things. So, the Strokes design ended up with a matrix of wash behind an X shape video walls. So much fun to lay with this rig.”

You’ve always been a gifted busker. What advice do you have on busking successfully?

“Maybe I used to be good back in my club days, but I haven’t busked regularly for so long. I think the key is always to have two options under your fingers. One option is to push further whatever is happening on the stage; and the other thing is to swop everything if a break is coming. Another thing, I should add is to practice. Back in my club days — kudos to Le Ferrailleur, in Nantes, France — I was doing four to five shows a week with bands I’d never heard before. That was awesome training.”

You mentioned busking back in your club days. How do you run your shows today?

“I don’t busk at all these days. I make cue lists, but I always keep parts to play with a few buttons on every songs. Depending on the songs the pattern will be less or more intricate. I’m not a big fan of timecoded shows on rock performances. You just losing the feeling — everything is too tight. Sometimes it’s necessary, depending on the project and music genre, but when it can be avoided, I’d rather play along with the band.”

“Speaking of playing along with the band, do you have to like a client’s music to do a good job lighting it?

“It’s better if you do, but you can always find something in any music that will inspire you. Then, after a month working on a project you ‘ll like it. Maybe it’s just a kind of Stockholm Syndrome! All jokes aside, it is a definite plus when you like a client’s music, which I do.”

A lot of new technology, particularly VFX types of tools have become more prominent in lighting recently. Some say this takes away from the raw organic flavor of lighting. Given that your shows tend to me powerful in your face creations. What is your feeling on this?

“I think that when the LX team have the control of the VFX it’s always better. Lighting and video can come together. But I’m a bit tired of having VFX in every show. Most of the time contents don’t bring more to the show or song. I feel like it’s there, just for the sake of saying it’s there. It’s not a necessity to have video. I really think a good light show can be self-sufficient in a big production.”

You make great use of atmospherics. How do you decide when and how much to use these effects?

“The biggest challenge is to achieve balance. With rock and metal acts the audience needs and wants to see the band plays, so the haze needs to not interfere with the music. But then you need to know when to push it to give more depth to everything, and work with more volumetric lighting. I tend to use a solid amount of haze as a first layer and then I’ll push with smoke when needed to create this end of the world feeling. It’s also good to have hazer at FOH, to be sure that you have clean looks with the light beams in the audience.”

How did you get started in lighting design?

“As a young musician I was attracted to the tech aspect the music, so I attended a lighting school. The people there told me to volunteer on events to get more experience before attending the school. So, I did that for a few events. But in the meantime, I reached out to my local venue (le VIP, Saint Nazaire) and ask for an internship. The only thing they could offer was catering, so I started there. I was always looking over the shoulder of the LX tech. After a while, they just told me to stop catering and come help them. And I have never tried the school admission again because I learned everything with the boys and girls at the venue.”

Are there any projects that have been most influential in your career. The jobs where you learned a lesson about what to do (or not do) that have stayed with you?

”I spent seven years with GOJIRA on the road. They are such perfectionists with everything. Light, sound, backline setup on stage. Everything needs to be perfect every night. We were recording the show and watched it back every single night with the band to make sure everything was perfect. That was intense, but I learned so much. The drummer was even teaching me time signature to make sure I can play some strobe pattern to perfection. I learned a lot with them on how to approach a show with the right mindset.”

You moved from France to LA, before returning to France. Do the two locations influence your creative process differently?

I don’t think the location changed my creative process. But the weather for sure can be a challenge. It’s so hard to stay inside and program when you can go to the beach to surf every day! I moved to Rio de Janeiro at the end of 2019 and I had the same problem. It was really hard to stay inside and work. But in the meantime those two cities are really stimulating, giving me tons of ideas for shows. The thing with LA and is that is so easy to connect with everyone in the music industry, but also it feels like you can’t take a break from it.

“The real question is how hard it is to work and keep working when you are not living in a major music city like, LA, London, or Paris? Due to Covid I just moved back to a small city in France. Definitely easier to work as it rains half of the year but it’s also hard to stay connected to everyone in the business as you are not living next door.”

On the subject of inspiration, how do you get inspired at the start of a project?

“It can be by doing anything. I usually sketch a lot on pieces of paper before doing any 3D. I listen to all the music materials, read and watch artist interviews on their influences, look at past shows. Trying to understand where they came from and where they want to go.”

You’ve had a long relationship with many of your clients. Do they offer any advice on lighting their shows to you?

“It depends on the clients. Some just want me to be free and try anything I have in mind, while some are more directive and have a vison of what the light show should look like. Marilyn Manson is in another category. He know what he wants to achieve and sometimes calls for more strobes or Smoke during shows.”

What is the toughest thing about your job?

“Being away from family and friends, the stress and the constant travels. It’s definitely harder post COVID. After two years away from touring, realize how hard it is to tour worldwide. It’s really hard on the mind and the body.”

What is the best thing?

“The Hour and a half of playing a show and feeling the energy of the crowd.”

How do you want to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“I don’t necessarily want to be remembered, but if I can inspire someone somewhere to fulfill a dream, I would be happy. I come from a small village of 4000 inhabitants in the middle of nowhere in France and I designed for famous acts and Grammy winners. So everything is possible.”