Mike Berger’s Universal Light

Posted on December 31, 2019

As a student at Carnegie Mellon University, this Los Angeles based designer was taught that the same core principles of lighting apply across all disciplines, be they architecture, broadcast, theatre or concert. Although the techniques and technology employed may vary, at its heart the driving force behind lighting design is universal, applying to all areas of endeavor.

Berger has convincingly demonstrated the value of this lesson already in his young career. Joining Full Flood after gradation from college in 2012, he has amassed an impressive portfolio as a Lighting Director, having picked up two Prime Time Emmy Award nominations and worked on major televised ceremonies like the Academy Awards and Grammy Awards.

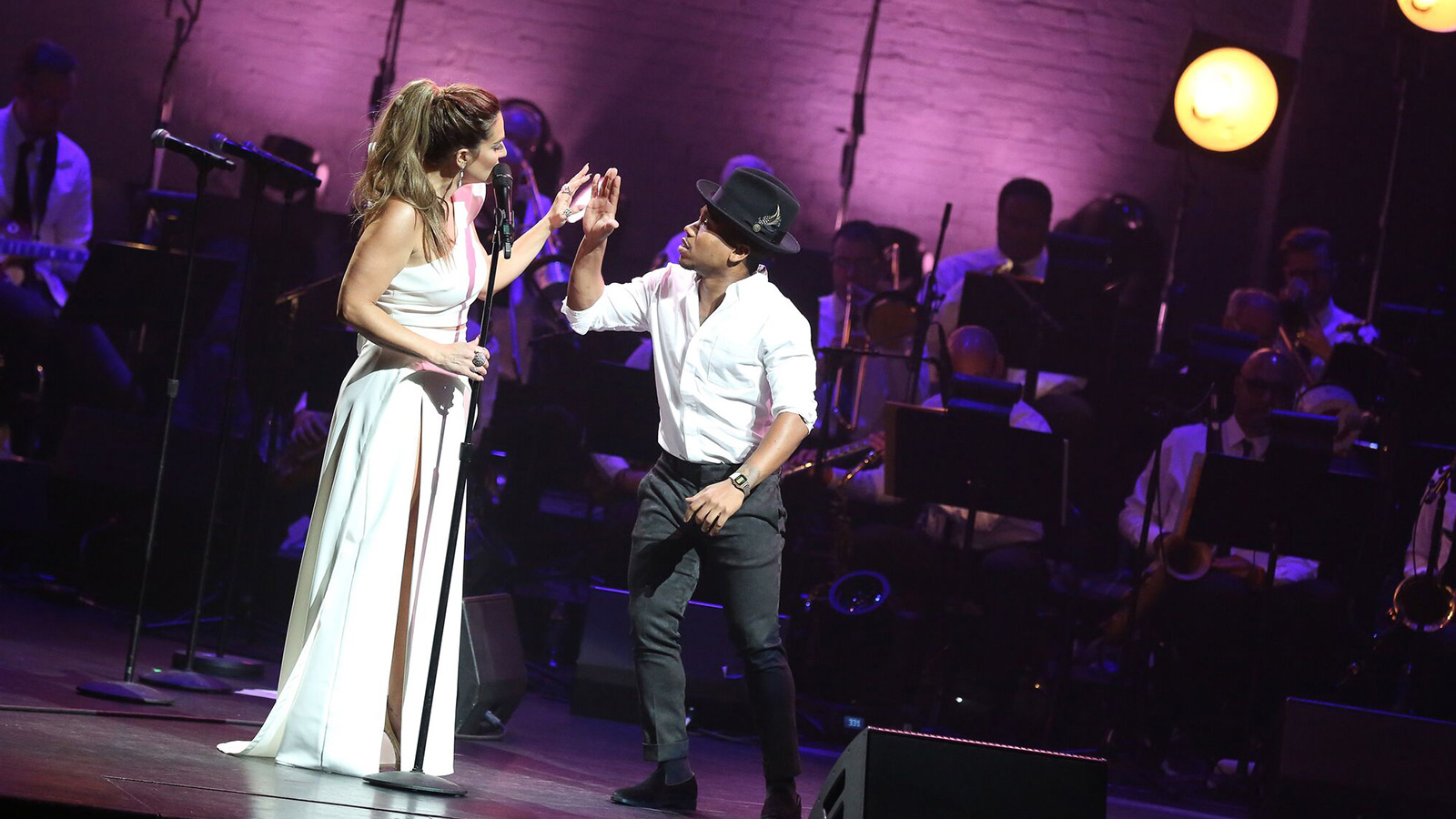

Taking concepts honed from his experience in broadcast lighting, Berger has used them to shape refreshingly original designs in theatre and concert applications. His work on the musical Scorsese: American Crime Requiem incorporated pacing and focusing techniques from television, winning him an Ovation Award for lighting design. He also earned widespread acclaim for lighting the nationally broadcast Boston Pops 4th of July concert.

Speaking to us from the ,, where he was prepping for another awards broadcast, Berger shared his insights into applying the universal principles of lighting design across genres.

As part of Full Flood, you’ve worked as a lighting director with Bob Dickinson on the Academy Awards, The Grammys, Golden Globes and other big TV events. You’ve brought that experience to theatre in your own designs for shows like Scorsese: American Crime Requiem. What are the lessons you learned from award shows that helped you in theatre?

“I’ve been really blessed to work with some incredible designers in the television world so far in my career. They’ve all had a huge impact on not only my design aesthetic, but also the way I work with lighting/production teams. The two biggest takeaways I have had from the award show market is that it’s intensely collaborative atmosphere and extremely fast paced. Speaking first to the speed, coming from a theatre background in college I was initially blown away at how quickly looks were built in a television setting. Watching programmers like Andy O’Reilly, Patrick Boozer and Ryan Tanker work has given me a lot of great processes that I have moved into the theatre/live event world.

“In terms of collaboration, I will tell you that the collaborative nature of television is unlike anything I have experienced. It really promotes an environment where everyone’s voice is valued across disciplines. I’ve tried to take this approach with me into other projects. The opinions and insight from other members of the team help to make a product that I find to be more well-rounded.”

Regarding the Scorsese show, we were impressed by how you used shadows and dark spaces to evoke gangster like imagery. Can you talk about how you view darkness, and the role it plays in your design philosophy?

“I first have to give a huge amount of credit to my co-designer on the project, Dan Efros. He was really responsible in the room for crafting a lot of those looks. I personally am a big fan of the absence of light in a scene. The areas of darkness are as effective in telling the story as the areas which you choose to light. I think this applies not only to the overall scene, but to the actor as well.

“We spend a ton of time in television ‘focusing’ on the closeup determining how the face of the character should look. Dan and I carried a lot of this over into Scorsese, appreciating moments of half light and even total darkness. I also enjoy playing with the audience’s own internal iris. Using specific moments of audience blinding light can help adjust or unsettle their eyes coming in or out of a scene. This, combined with appropriate staging, can help sell a gunshot, or a transition.

“The For the Record team that did Scorsese has been incredibly supportive of the use of shadow and darkness in production. They’re always willing to try something unconventional and I find that helps us get to a great image at the end. We’ve also adopted a more television process in our tech, which allows us to get more done in less time, and in turn, tackle more projects together.”

Scorsese featured a mashup of songs that were used in his films. You also were involved in other mashup productions like Brat Pack on the NCL Escape and Baz: Star Crossed Love, which had a successful two –year run at the Venetian in Las Vegas. You used a lot of movers and blinders in those shows to create disco looks that often involve the audience itself. How did you do this while still staying within the bounds of a theatrical production?

“A lot of this comes from our desire as a team to create an immersive experience. I want the audience to feel like they are a part of the show, not just attending a performance. The best way to do this is to bathe them in light that is similar to what is onstage. We have found that once the audience gets accustomed to the concept, they embrace it and welcome the involvement in the performance. It also gives us a great opportunity to flip the switch and go back to a traditional theatrical look when the story requires it.

You have a strong technological background, graduating from Carnegie Mellon. As a designer how do you achieve a balance between technology and art, using it to advance your design concepts, but not using it just for its own sake and having your design subservient to it?

“I think it is incredibly important for a designer to be well versed in not only the technology but the programming behind it. This helps you spec the right tools for the job and understand the limits of each fixture. I always try to stay ahead of the curve with technology, but have also developed a reputation for digging deep in the back rooms of the shop for something very old. My education at CMU was great at teaching both the technology and also the process. We are taught how to ‘light’ not how to be a theatrical designer, or a television designer or an architectural designer – but simply how to be a lighting designer. You are given the tools, both creatively and technically. You need to walk into any setting and craft the right moment.”

Ok, so on the subject of technology, do technological breakthroughs in lighting give you new ideas, or is it just a matter of technology making it easier for you to achieve what’s already in your head?

“Definitely a little bit of column A and column B. When something new comes out I am immediately thinking how I can use it, or how I can apply what it can do to something old. I also really enjoy talking with manufacturers about what is in my head and then see it show up in future products. It’s always a fun back and forth when you get a good group of creators and creatives around a table.”

If we can return to your work in award ceremonies. At most of these events you typically have a wide variety of presenters and winners. How do you keep the key lighting right with all those people?

“Fortunately, on a lot of these projects we have an opportunity to rehearse and adjust at least the performances. Outside of that, we work collaboratively with the video controllers, our programmers, and follow spots to adjust intensity/backlight on the fly as necessary.”

How would you define the role of lighting in an awards ceremony like the Oscars?

“I’m actually backstage at the Dolby right now, so it’s a geographically appropriate question! With a show like the Oscars, we are a part of the biggest night of someone’s life — they just don’t know it yet. It’s our job to help make the capture of that evening as perfect as possible. We want to make sure everything looks good from every angle. It’s not just about our broadcast either, there are hundreds of photographers, iPhone and other recording methods that also capture the show. We need to be cognizant of creating that image as well.

You’ve worked quite a few film related events and ceremonies. Are there any film directors, past or present, who you think would have made great lighting designers?

“Hmmmm interesting question. I think the answer really relies more in the hands of the Director of Photography/Cinematographers. I’ve always been a fan of Roger Deakins’ work. I find he has a knack for really looking outside the box, which I appreciate. I’m a huge fan of Baz Luhrmann’s work. Perhaps that comes with the For The Record experience. He has a great eye for the theatrical and composing a story. I think his eye would translate well onstage.”

It seems that video panels or projections are occupying a more prominent spot on broadcast sets, whether its at an award ceremony or another type of program. How does this impact lighting design?

“There is a ton of truth to that. Video is becoming the new scenery, for better or for worse. It affords an incredible amount of flexibility for the design team but also adds a new level of challenges. The intensity and color balance between faces and projection/LED becomes a very important place to start. Often you have to pull LED down very far in brightness to get into the right realm for key light to read.”

We were impressed with how you wove the historic DCR hatch shell into your design for the Boston Pops Independence Day concert. You kept it visible even as you had a very bold and massive lighting display. Can you talk about that?

“With that show in particular, the set really is the architecture of the space. Since that shape is so iconic, we try and really embrace that shape in the design. That starts with the big semicircle truss that was custom built for the opening of the arch. The curved shape really lent itself to some great sweeping beam looks that Ryan Tanker, programmer, put together. The event really strove to evoke the feeling of both an orchestra concert and a rock show. Incorporating the shell in the design allowed us access to both. We can embrace its subtlety in one number and also blow it all away when called for.”

At an event like the Boston Pops concert, which is seen by millions on TV, but also attracts a very large crowd, how do you balance lighting for live and broadcast audiences?

“When I’m working on something televised such as this the primary goal is to capture the best image as possible on camera. This sometimes does involve pointing lights at the audience in order to expose them properly. We do our best to try and be sensitive to those watching the show live. Lately I’ve been trying to push the lighting of the audience into more immersive looks, rather than just corrected key light. I find that this gets the crowd into the mode that they are enjoying a concert rather than being filmed for television.”

How did you get started in lighting?

“Back towards the end of middle school I started my own mobile DJ business. I was doing a lot of birthdays, weddings, Bar mitzvahs etc. and was much more interested in the lights I was bringing than the flow of the party. As I moved into high school, I quickly got involved in theatre and, as the only person interested in designing, took that role immediately. From there I went off to Carnegie Mellon, where I had a lot of incredible opportunities to intern both in theatre and television. Through those experiences I found an interest in both areas and have tried my best to pursue work in each of them.”

What is the most rewarding thing about your job? What’s the most challenging?

“The most rewarding part for me is getting to watch a cue execute perfectly live. There is nothing like being in the room or in the truck watching something that you crafted unfold for the audience to see. The most exciting ones for me are when it elicits a reaction you didn’t expect. Of course, I would be naïve to think that these moments are purely lighting centric. What makes them really special is the collaborative process that got us to that moment. I think the best part of this job is getting to work with your friends and make great pictures. There’s nothing quite like this industry. I have been blessed with the opportunity to travel the country and parts of the world doing what I love with some of my best friends. Every day I get to go into work and create something new, and that is truly rewarding.”

You’re young, but we ask this to everyone – so how would you like to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“Ha! Ideally for something I haven’t done yet! I’d like to think I still have a long career to go and lots of looks to develop. I can’t wait to see what those things are.”

Editors note: Neither can we!