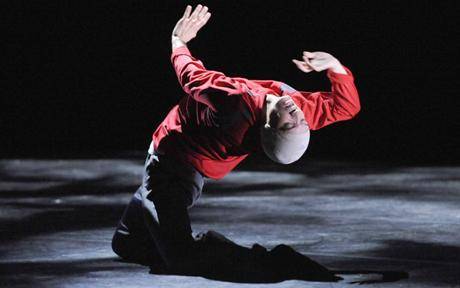

Michael Hulls: Expansive Light

Posted on March 5, 2019

Photo: Chantal Guevara

The allure of light lies not only in what it does, but also (and more importantly), in the ever-present promise it offers for more. Delicate and ephemeral, light is always ready to be taken in new directions, going beyond what is at any moment to something larger and greater. It is the pursuit of these expanding possibilities that has been at the heart of this British designer’s celebrated career.

Winner of multiple Olivier Awards and Knight of Illumination Awards, Hulls has collaborated with many of the world’s leading choreographers, most notably Russell Maliphant, to pioneer new concepts in dance lighting. He is one of only four lighting designers to have an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of Dance.

In 2016, he attracted international attention for his creation LightSpace, a choreographed show at Sadler Wells made up entirely of lights with no human dancers. Although some expressed unease about a “dance without dancers,” for Hulls it was just another instance of pushing the boundaries of light.

Like a sailor approaching the horizon, he never expects to reach the limit of what light can do, but it is the journey that makes the exploration worthwhile. Speaking to us from his London studio, Hulls shared his insights into expanding the possibilities of lighting design.

What role do you see lighting playing in dance?

“I see light as acting as a catalyst for creation, something to be at the forefront of the creative process. Its role is to create a fluid choreography of architecture and of space and time that is indivisible from the dance choreography. It helps create an abstract emotionally engaging experience for the audience.”

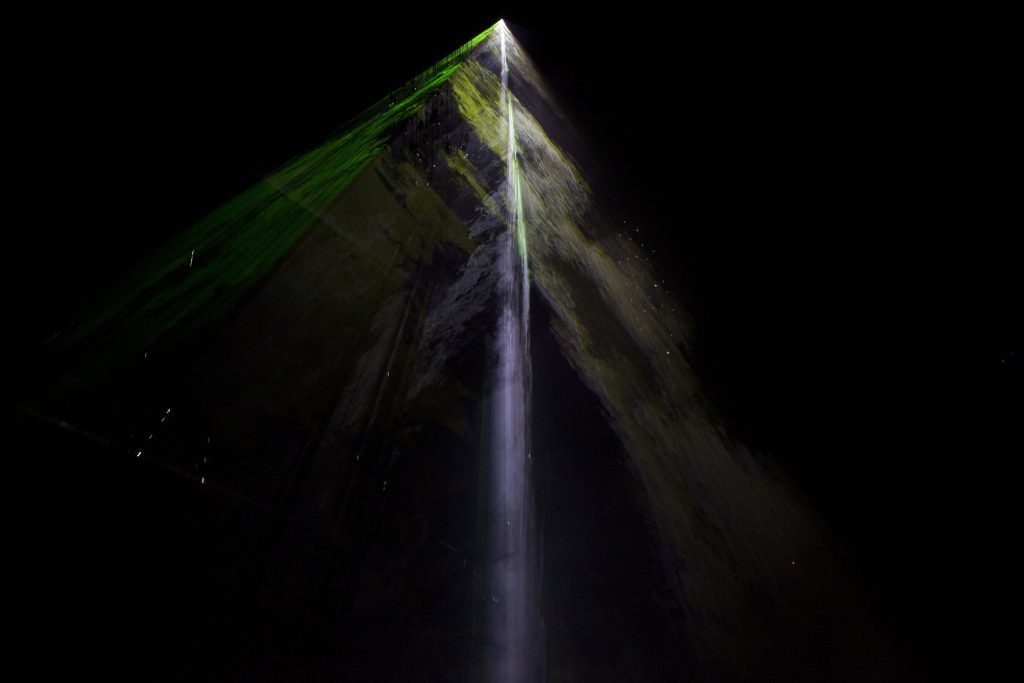

Photo: Hugo Glendinning, Charlotte MacMillan

Do you alter your designs depending on who the dancers are?

“Only in respect to the size of an area of light that the dance is happening within. For example, we made a solo that originally happened within a two-meter square of light, but when a taller dancer took it on it became a 2.2 meter square, and then when superstar ballerina Sylvie Guillem took it on it needed to increase again to 2.4 meter square to accommodate her greater extension and longer reach.”

Do you light a dance differently when it is being broadcast on TV?

“Only to maybe push the light levels up a bit to make sure you have captured what needs to be seen in the knowledge that it can then be taken down again in post-production.”

It’s been said that dance, like theatre, can be taken on a multitude of levels from the superficial to something appreciated for its deeper meaning. Do you think the same thing is true of dance lighting?

“I think dance lighting has the potential to do exactly that in terms of deeper meaning, more so than lighting in any other medium or form. I mostly work in abstract dance and that is where I see the greatest potential for light to be whatever it wants to be, whatever it can be.”

Speaking of the emotional power of light, you earned widespread praise for creating LightSpace, which in essence may be viewed as a choreographed production featuring light without human dancers. If you were on a short elevator ride with someone and they asked you “What is LightSpace?” What would your brief answer be?

“It’s an immersive light installation with you at the center, but it’s also a show, as it has a beginning, a middle, and an end.”

Can you tell us a bit about how the concept of LightSpace came about?

“All the Associate Artists of Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London, of which I’m one, were asked in 2012 to create a five minute ‘turn’ for a fund-raising dinner on the main stage. I made a gentle descent of 130 random twinkling par cans from the grid to about five meters above the 300 diners. At that height, they all started to work in unison a slightly malevolent way. And then in an instant they all suddenly went to Full and dropped to be just a foot above the heads of the dining patrons. There was a loud gasp from everyone and then applause for such a thrilling coup de theatre.

“The Artistic Director and Chairman of the Board of Sadler’s Wells then asked me if I would undertake a commission to create my own light show on the stage. After two years I decided to agree as I then knew that I wanted the installation/show to start with a Tungsten Requiem for the humble, yet a fast disappearing-from-our-world, lightbulb. And of course, I wanted the par can Crash to be the final moment.”

Photo: Hugo Glendinning, Charlotte MacMillan

Some people who saw LightSpace said it was scary to see a choreographed performance evoke such powerful emotions without human dancers. How would you respond to that?

“That’s great that they had, and recognized, that strong emotional response to light, since it’s so often overlooked or confused with responses to a variety of other stimuli. Although there was a composed soundtrack for LightSpace that would also contribute to people’s response it seems easier to identify that emotional response to light without the presence of a human performer.”

Why do you think LightSpace is so moving?

“It creates a purity of space and environment for our emotional responses to light to flourish; and light is incredible psychoactive, it constantly shifts our mood and emotions and by progressing through a variety of different lighting states and landscapes that are quite different it encourages us to experience different emotions and energies. Fundamentally light is energy and we respond emotionally to energy, so there was a conscious attempt on my part to create different responses and moods from the gentle and soothing to the violent and threatening.”

Back to the subject of lighting human dancers — you’ve had a long and wonderful history of collaboration with the choreographer Russell Maliphant. Can you tell us how that started?

“I had just become a lighting designer by accident when a dancer, Laurie Booth, suggested that I come and do some lighting for him — improvised lighting for improvised dance. The second piece we made was a duet between Laurie and Russell, both improvising as was my lighting. Russell and I recognized something exciting going on between light and dance in those improvised performances that we decided to make our own collaboration, using improvisation as a way to discover material to then make structured non-improvised pieces that explored this relationship between light and dance.”

What are the keys to successful lighting designer/choreographer collaborations?

“The key is to have a shared aesthetic. For Russell and myself this is a sculptural appreciation and interest in the human body as a 3D moving sculpture. The ability to learn from each other, and to trust that you both might see something interesting that the other has missed is really important.”

We’ve seen a lot of new technology emerge in lighting. Has this impacted the way you design for dance?

“Not really. There’s a couple more tools in the kit but we’ve been swamped with mediocrity.”

Photo: Chantal Guevara

What are your thoughts on using moving fixtures in dance?

“Some are potentially great tools to help create movement through lighting. The movement is the interesting feature, but their development is driven by big budget applications where speed and the spectacular are important rather than the slow and subliminal which is much more useful for me. When I get to try out a mover the first thing I want to see is how slowly it can pan and tilt, how slowly can the shutters move before it starts to judder or step. I’m interested in the purity of its light and motion, not all the flashy effects.”

When you sit down to design for a dance, what are the first things you do?

“Ideally, I don’t sit down but rig a light and try something out, try and discover some interaction between light and dance that makes me think it could be the basis of something.

If I do have to sit down it’s to try and find out where the edges of the frame are. Where are the boundaries that I’m working within, what’s the limit of possibility?”

Who were the big influencers in your career?

“The pioneering dancer Steve Paxton who taught me at Dartington, Laurie Booth who had also been taught by Steve and introduced me to the work of Jennifer Tipton who made me realize what I wanted to do with light and dance wasn’t a ridiculous idea.”

Where do you think dance lighting is headed in the next decade?

“Hopefully avoiding the pitfalls and glossy temptations of being swamped in digital technology and remembering the human experience and emotion.”

Your work has been widely praised for its emotional power. This may be an impossible question, but what makes lighting an emotional force in dance?

“Its intangible nature. Lighting’s presence is so ephemeral, and it’s so poetic in the sense that it can be incredibly suggestive of something greater and beyond what we are actually looking at.”

How would you like to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“As someone who made it up as he went along, and hopefully contributed to expanding the possibilities of light.”

Photo: Heathcliff O’Malley