Johanna Town Heightened Light

Posted on June 27, 2019 At the start of every project, before she even begins to put together a lighting plot, this celebrated British LD and chair of the Association of Lighting Designers reads through a script and lists the colours she associates with each character and scene. Many of those colours will never appear in her final design; practical (as well as aesthetic) concerns will likey preclude that! They are chosen instead for the feelings she attaches to them. It is this emotional energy that will inform Town’s design decisions, sharpening the power of her lighting to heighten the sense of time, place and most importantly, character on stage.

At the start of every project, before she even begins to put together a lighting plot, this celebrated British LD and chair of the Association of Lighting Designers reads through a script and lists the colours she associates with each character and scene. Many of those colours will never appear in her final design; practical (as well as aesthetic) concerns will likey preclude that! They are chosen instead for the feelings she attaches to them. It is this emotional energy that will inform Town’s design decisions, sharpening the power of her lighting to heighten the sense of time, place and most importantly, character on stage.

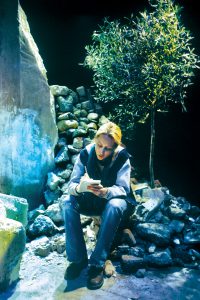

Facial lighting occupies a particularly important place in Town’s design paradigm. Although her work in shows with elaborate sets has earned widespread acclaim, she never loses sight of the basic principles involved in lighting characters to best accentuate the emotional impact of their performances. She leaves no stone unturned in pursuit of this ideal. Paying careful attention to every detail, she routinely adjusts designs to fit even the smallest difference among venues on tours. She also eagerly explores new technologies that offer the promise of expanding her creative options, as exemplified by her early adoption of LED fixtures.

Town’s career in lighting began when she was 16 and got a part time job running boards at a local pier theatre. The journey has taken her very far indeed since then, having seen her serve as head of lighting at London’s Royal Court Theatre for 17 years, in addition to designing major productions at the West End and on Broadway, as well as at The National Theatre, RSC, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Sheffield Theatres, Royal Exchange, and Chichester Festival Theatre.

The desire to give back to the industry has motivated her to serve on The Association of Lighting Designers. She spoke to us about her inovlvment in that organization, and shared her insights into the intensifying power of light.

If someone asked you what’s the main purpose of theatrical lighting, what would you say?

“Lighting is supposed to make an audience understand the story. This may be through dramatic effect, or as a result of creating a sense of a real location, while getting across the mood of that location. To help direct and tell the audience what they should be looking at on stage, that’s the objective of lighting.”

You’ve said that LED moving lights have become a main fixture in your theatrical rigs. What is it about LED technology, and what is it about moving fixtures, that have made them so appealing to you?

“I love any lighting fixture that gives me flexibility and opportunity to develop creative ideas. I have always been a fan of tungsten moving lights over discharge, as the colour of a discharge lantern often doesn’t work well in my lighting designs.

“The introduction of good LED and then later good LED moving lights has allowed me to create subtle naturalistic lighting, as well as strong dramatic work. When this can be done from the same fixture it is very liberating. LED has also changed the way I work with lighting on stage, I now shift from different colours on stage, rather than the intensity levels of lanterns in cues. This engenders the development of a design that maintains strong face lighting ,and also creates subtle emotional shifts.”

Now that lighting designers have more LED tools at their disposal, are directors more cognizant of how lighting can contribute to the unfolding of the story a play is telling?

“It has become very obvious over the past decade that directors, designers and producers have become more aware of what can be achieved with lighting. Designers are asked to make changes very fast and instantly. However, the people requesting those changes don’t always understand that this isn’t a simple fix, or something that can be done without incurring added costs. Programming time and the need for quality, well trained in-house programmers has been neglected by producers and theatre owners, which makes production weeks extremely stressful for lighting designers. There is a need to educate directors and producers about the skills required to use moving lights and program them fast and efficiently.”

Along similar lines, new technologies have made sets more elaborate today. Looking at your work on “Sir John In Love,” we were struck by how you brought out the nuances of Giuseppe and Emma Belli’s intricate set with all its buildings and other structures. How do you balance it and key lighting?

Along similar lines, new technologies have made sets more elaborate today. Looking at your work on “Sir John In Love,” we were struck by how you brought out the nuances of Giuseppe and Emma Belli’s intricate set with all its buildings and other structures. How do you balance it and key lighting?

“’Sir John In Love’ was complicated, the sets were actually all cloths and it was part of my job to make them feel real and 3D. I had to be strong with my scenery light and kiss in key light. It was a constant rebalance between the two.

“I paid attention to all the different sets and what they require from the lighting to make them dramatic to the audience. I then designed the key lighting to work without lighting the scenery. When programming, I touched in the amount of light I actually needed to bring out the singers, as lighting the cast is the most important thing to me. Later during the previews, I rebalanced the set to come out as required against the key light.”

You’ve worked on “My Name is Rachel Corrie” at the Royal Court, and in the West End as well as in New York. When you light the same show at different houses, do you adjust your design to account for the nuances of different venues?

“Absolutely, every auditorium creates a different relationship with the actor, and the audience experience. It’s important to think about what I am trying to convey to an audience from a light point of view.

“Also, technically we have to look at all the different lighting positions available. These will also be different with different angles to the stage that will affect how the light falls. With regards to ‘My Name is Rachel Corrie,’ in that case, the set designer also had to create three different designs to suit the different auditoriums, and because of this, the show’s lighting had to change. I believe this makes the design more exciting; I am not into copying and pasting the design but having to examine what is important to it and make that work.”

You also designed “The Marriage of Figaro” at Almeida Theatre and the Opéra de Nice. How does lighting opera compare to lighting theatre?

“They are such completely different mediums, so they do have to be approached very differently, but I do try to maintain my basic lighting principles of being able to see performers and to heighten reality during a production.

“I have lit ‘The Marriage of Figaro’ four times in my career, each venue, set design, and directorial discussion influenced my lighting designs in very different directions. For each discipline does have its own rules that can be followed and broken. So, I think I actually approach each design from a zero point of view, completely individually and on its merits.”

When you begin a design project, what is the first thing you do?

“I begin by reading the material, whether this is a score or a script or both. Then I list my own physical and emotional notes from the text, this is done by listing colour by the text and how that colour makes me feel, it very rarely will be the colour that is used, it is something I do to short cut my emotional feeling towards the script at the time. I might note an artist or a piece of work. Next follows discussions with the director and set designer in order to work together towards a single vision. The technical and physical aspects of the design continue on from the creative vision of the design.”

So before you do that, how do you get inspired? Long walks? Listening to music? What gets your creative juices flowing?

“I am inspired by the world around me, yes walks, watching the light change over a day, be that in a city or the countryside, each has its own place. I also sit in public places such as offices, restaurants, and galleries and watch light on people. I have been accused of staring! I also like to be free from my desk and the computer and develop an idea in my head. When I do this, I walk the dog or play golf on my own.”

What’s the key to successful collaborations with set designers and directors?

“Being there from the start for the first discussions, being part of the whole process, building dialogue between everyone leads to good collaboration.

I look at the whole production, what it needs to achieve the director’s vision. It’s important to have ideas that are not just about lighting.”

In “A King’s Ransom” you used gobo patterns to evoke images of a forest. How do you use gobos to create this kind of effect without distracting from the actors?

“’A King’s Ransom’ is a children’s opera and the children were part of the ideas behind the shows designs. The children wanted the show to be very visual. Most of the show was set in a forest at night; they wanted to feel the breakup of the forest on their faces and their friends’ faces. They wanted me to use lots of haze and atmosphere, the leaf breakups were part of this. I then balanced with strong front light. The aim was for it to work with the children and not against what they wanted to see, working a design hand in hand together.”

You aren’t afraid of using dark spaces. Some designers seem to feel reluctant to have too much darkness on stage. What are your thoughts on that?

“On some productions it’s the darkness that brings out the atmosphere of the production. The audience has to feel the same intense fear or anxiety as the actor. Though I like darkness I feel it’s the lighting of performers that is most important.”

Many of the plays you’ve worked on have been broadcast on television. Does this affect your lighting design?

Many of the plays you’ve worked on have been broadcast on television. Does this affect your lighting design?

“I have had several productions put onto film. This is usually after the lighting design has been completed and the show is open and running in front of an audience. Usually I work alongside the camera / lighting man, adjusting the lighting to make it the best for film, without detracting from the audiences’ experience on the night.

“It is never perfect, as each medium uses lighting very differently, the camera often seeing a small proportion of the whole effect shown to an audience. It is often the edit that can then make it look good or bad. If the film watcher doesn’t see or understand the source of the light, it can seem somehow odd. To be honest, I have never really been satisfied with the end product.”

You are the chair of the Association of Lighting Designers, and you’ve been very active in industry groups. Why is that?

“I have had a very happy and successful career in theatre. I started when there were not that many women in the UK working in the industry. So it was important to me to give a little back. I want to be an inspiration and a role model to women who want to work in theatre, especially in lighting.

“I also want to improve the working practices in theatre, from the hours we work to the health and safety, as well as encourage an increase in pay. Here in the UK technicians and designers have been left behind on the pay scales, and it’s important that we make the industry sustainable. I have seen too many very talented people give up their jobs in lighting, purely because it is not sustainable to live and have a family. This isn’t right.”

Looking at your career, is there one project that stands out as being an especially important learning experience or confidence builder?

Looking at your career, is there one project that stands out as being an especially important learning experience or confidence builder?

“Oh, this is a tricky question. Every show or project is a learning experience, whether you learn something about yourself or your work, maybe you just learn something new about life and the world. Not all confidence builders come from the shows that went well, you also learn from the shows that were a struggle or had difficult collaborations. I can’t think of one particular project that stands out. I can list a dozen or so that have shaped my career and my work, and these productions were when lighting, actor and direction managed to take the audience on a journey to somewhere else for a moment, and when this happens it’s magic.”

How did you get started in lighting?

“I started working with lights in a local amateur dramatics company when waiting for my mother to finish rehearsals, anything other than being made to go on stage! I loved it and when I reached 16 I got a job at one of our local pier theatres doing their summer season, school during the day and follow spotting at night. I also spent much of my youth watching productions at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester, and one evening I went along to the lighting box and asked, ‘How do I get a job in theatre?’ At the time, the theatre ran apprenticeships for lighting technicians. I applied, got the job, and at 18 started working full time in theatre and have never looked back.”

Who were the big influencers in your career?

“So many amazing people have passed through my career who have offered me advice and influenced how I have shaped my own career. But purely on a visual lighting design, I have to say it is the lighting designer Mick Hughes who has had the biggest influence on my work. I learnt from Mick how to create beautiful designs and still service a play. He also taught me how important it was to work as a team creatively and with the theatre staff who were helping you make your work.”

How would you like to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“As a collaborator, an artist and a team player.”