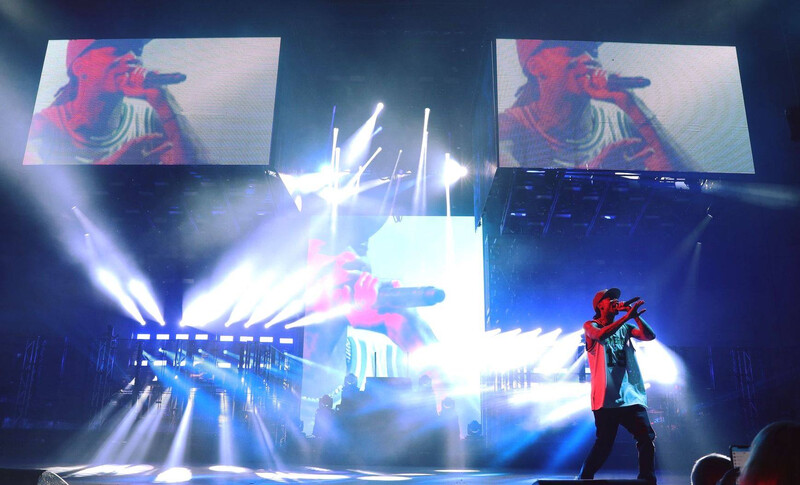

Jason Bullock – The Calculus of Light

Posted on October 5, 2021 Photo: Todd Kaplan

Photo: Todd Kaplan

At some point early in his career, this highly acclaimed New York-based designer and programmer began putting a sign behind his FOH position that read simply “Stand Back.” A warning to bystanders not to look over his shoulder? Perhaps, but there was also an element of safety in the message, as he had a habit of shoving his chair back and jumping to his feet as he busked his way through a show, often flinging his shirt off in the process.

Bullock’s animated busking style is legendary throughout the touring industry. Fusing an impeccable sense of timing and rhythm with an abundance of passion, he erases all space between the visuals his console controls and the performance that connects his client to the audience.

Underlying this unbridled emotional energy however, is an intense focus on the logical technique behind any design. Like a mathematician using calculus to breakdown the most complex formula into its most basic elements so it can be more readily solved, he is able to busk shows involving hundreds of cues by distilling the core principles that underly their design.

Mastering these concepts and precisely organizing every command on his console, he has turned out stunning shows for a range of artists, including friend and longtime client Wiz Khalifa, Nine Inch Nails, Janes Addiction, 311, and more. Speaking from his studio at Infinity Point Design, Bullock shared his insights into the calculus of light.

Before the pandemic, you did a show for Wiz Khalifa at the Coachella festival that was 90 universes with 21 pages of cues, yet you busked the whole thing. How do you manage busking something that big?

‘There are a number of ways to answer that. First there’s the relationship with the artist. I’ve been working for Wiz for a long time, so I know the general direction of where he’s going, even though you can never tell what he’s going to do at any given time during a show. Wiz is very prolific. He’s always writing songs. I might get the set list and see a song I never heard of, because he wrote it two days ago! So, I’ll go to the production manager and ask ‘what kind of song is this? What’s the mood?’ Then I’ll figure out looks that match it in light. Typically, Wiz would do one big show for a summer tour and I’d have two or three hours of material on my busking pages for lighting and video. If I’m busking and something comes up unexpectedly, I can always fall back on this material.”

You have a great working relationship with Wiz Khalifa, but what if you don’t go back that far with an artist?

“It doesn’t matter. Even if it’s a brand new client, you have to know the personality and the music, so you’re able to busk with some conviction. We’re lucky we have social media, so even with brand new clients you can learn everything about them. Learn all of their hits and watch them over and over again, because you know they are going to be a big part of your show. But don’t just stop at the music.”

What do you mean by that?

“The music is just the beginning. You also got to learn about the personality of the artist and the relationship he or she had with previous LDs. Did the LD before you get fired? Or was it a matter of that person moving on to something else? Either way, you should learn what you can.

“Also – and this is very important- learn who the people are who have the artist’s ear. You may think the that guy you see helping the artist take his jacket off before a show is just some old buddy, but he may also be the guy who hangs around FOH and tells the artist what the show looked like to the audience. Knowing the people around the artist builds trust, and trust builds creative freedom, which makes this whole thing fun.”

You said there were a number of ways to answer our first question about busking. So, what are the other things that allow you to busk the way you do?

“A big one is organization. The more organized you are, the simpler things are — and simplicity allows you to move fast. I always number fixtures by types, so it’s easy to call them up. I also have a space for a video page in the middle of my console. There are three pages each may have a hundred clips. I know them, so can call them up a good video in a snap. I may do this, for example, if I need a bridge to cover a gap in lighting.

Photo: Todd Kaplan

Photo: Todd Kaplan

“When you’re organized and really know you console well, you don’t have to spend time looking for what you want during a show. Console screens are not supposed to be part of the show, the stage is where the show’s at. So, you want to be looking at the stage, not at your console.”

Is that why you often are standing up rather than sitting when you’re running a show?

“Exactly! Standing up, you see the stage better. Also, and this is crucial, when I’m standing up, I’m moving my body, and the motion of my body keeps my hands in rhythm on the console. It’s kind of a holistic thing, where all the pieces come together. There is a musicality to it. I play drums and guitar and that helps busking.”

You also often take off your shirt when busking. Is that part of this process?

“It’s something I just do for myself, not interested in what others think about it. I started doing it when I was working with Nook Schoenfeld on the 311 shed tour when it was hot as hell. Nook didn’t teach me about taking my shirt off, but he taught me a whole lot about busking and lighting shows.”

Photo: Todd Kaplan

Photo: Todd Kaplan

What about the psychology of busking?

“Good question, because that is a key part of things. There is a big leap from being a programmer to being a designer who busks a show. That leap requires that you develop a very strong conviction that your vision is good. Hesitancy and doubt are big obstacles to creativity and execution. I’ve seen times where the LD is unsure of things so will hit the fader button tentatively, which doesn’t translate well to the audience.

“You have to have the conviction that if the music changes and you can’t follow your cue list, you can come up with something else that will work. You make an educated guess; and if by chance it doesn’t work, you can change it in a few seconds, like at the first downbeat. In the bigger scheme of things that’s not going to take away from the overall impression created by the show.”

So, you’re kind of like acting like the editor and the writer or conductor and orchestra at the same time, evaluating your work and adjusting it in real time as you create it. How stressful is that?

“It can be stressful, but remember, if you know your client, are organized and have the strength of your convictions, it’s manageable. Plus, I like to build out my rig to handle different contingencies.”

Can you elaborate on that last point?

“Everything I build is designed to scale down or scale up. You need to be able to scale down any rig got to be flexible. You may have a 40-foot trim one night, but a 28-foot one the next. You need to put units of each fixture in multiple locations, so the context of your show will look will be the same if the size or configuration of your rig changes – and if some sections have to be eliminated.”

You can do that while still maintaining the essence of your show?

“Yes, if you understand what the essence of your show is all about. There is always a core meaning or look to a show. Sometimes you have a lot of extra fixtures to enhance it, but what it comes down to is the same core. So, you have to know how to preserve that as things change on a tour.”

So, it’s like a calculus of light. Taking a complex show and breaking it down to its core?

“Yes, like a form of data compression, where you identify the key elements of something, and then us that to manage it. This goes beyond what kind of console you’re using, or how many fixtures you have or don’t have. Every show has its core – the thing that’s at the heart of the design. If you stay focused on that, everything else will pretty much follow.”

When you start putting together one of your flexible designs, what’s the first thing you look at?

“Early on in the process I start making a gear list. I have an idea of what kind of show we need to create based on research and conversations with the artist’s team. I also know if there are any big scenic pieces that I’m going to have to account for in my design. Once this is done, I select the fixtures. The capabilities of the fixtures are going to determine what I can and can’t do. There are always budgets involved, so you have to be realistic too. I’ll look at what a fixture can do and work around that when designing.

“I will also look at what we can do with set design elements and automation. You have to be pragmatic. Automation is astounding, but it’s costly and time consuming to set up. There are also safety issues; so, I will never put motors in a center stage position. When all is said and done, though, it’s the total picture you’re able to create that matters. It’s not your rig, it’s what you do with your rig that counts.”

You run video panels or projections yourself. Why is that?

“Again, it’s a matter of control and being responsive while busking. I can’t be busking lights while someone else is going off in another direction on video. I don’t create video content, but once it’s created, I will control it. Not just where the video images are placed, but I’ll also mix and blend it, adding colors or ratioing out some low res images to make them look better.”

You’ve had some big video panels in some of your designs. What are your thoughts on using video in shows?

“It has its place, but you have to manage it. I think there are some concerts today, where you’re seeing a music video rather than a show. Video can quickly take over a stage You can have a Nimitz aircraft carrier filled with lights, but a video wall cranked up can wash it all out.

“Really, in general terms you don’t want to go big just for bigness’ sake. Some of the best shows I’ve been involved with have been pretty basic. I was the LD for Roy Bennett on Nine Inch Nails’ Ninja Tour in 2009, which I punted using three primary colors and white. We got into a rhythm with the band and it was beautiful.”

What do you think you would have done if you didn’t become a lighting designer?

“I probably would have been in the Navy. My grandfather, Frank Bullock was a Navy man. In the 1970s when he was out of the service, he started a business servicing these new things called computers. When I was a kid, I would have to help layout circuit boards before I went out to play. That’s where my tech orientation started.”

Photo: Todd Kaplan

How would you like to be remembered as a designer?

“I’d like to be remembered as a good guy – also as someone who believed in his work and stood by it, as well as someone who helped the people coming up after him. I don’t think it does much good to learning anything if you don’t pass on your knowledge.”