Felix Peralta – Lyrical Light

Posted on February 6, 2024

Does a lighting designer need to have a musical background to create an evocative show? This Emmy winning Muscle Shoals, Alabama-based LD says it isn’t absolutely necessary, but allows that one way or another, musicality and rhythm must find a way to run through the heart and soul of every memorable lighting design.

A former drummer, Peralta makes music his guide when approaching every project as a lighting designer, director, or programmer. Going beyond understanding the mood of the music, or the meaning of its lyrics, he delves deeper, striving to reflect its timing, pacing, and tempo. To do this, he will often reference masterpieces like Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings with its huge crescendos, to help him envision how his lighting will reflect the many dimensions of the music being performed on stage as it moves through its own ever-changing narrative.

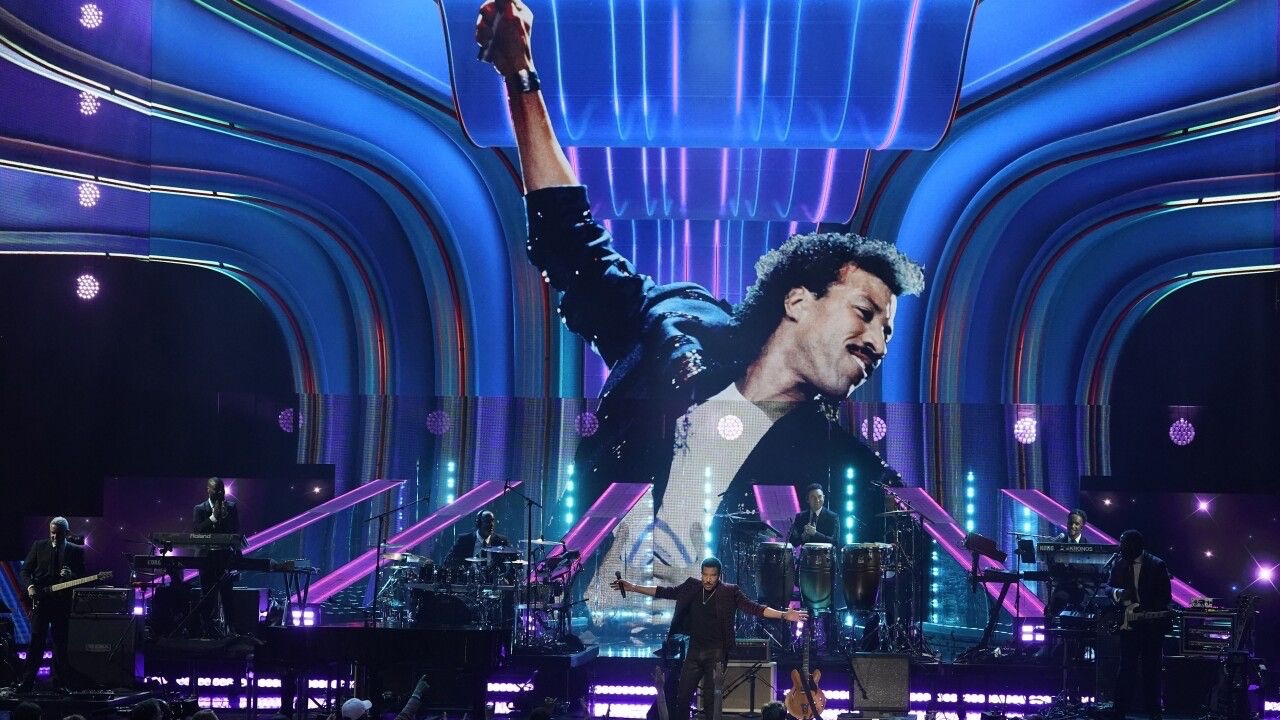

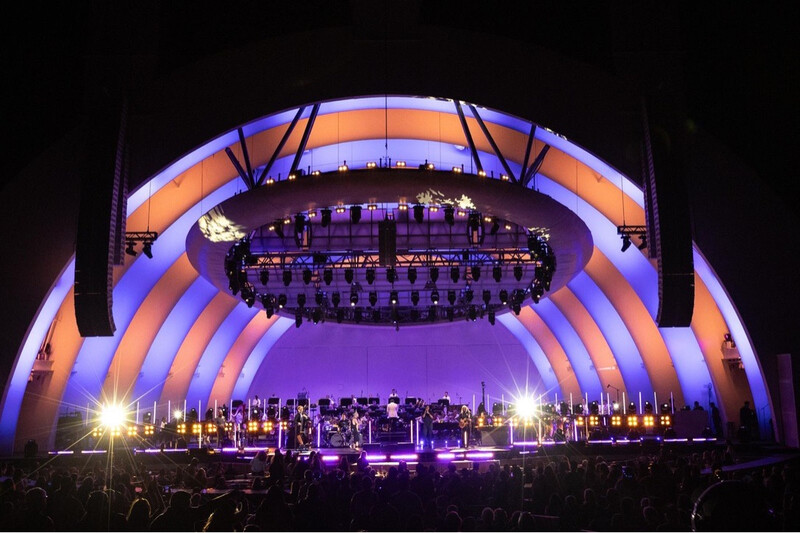

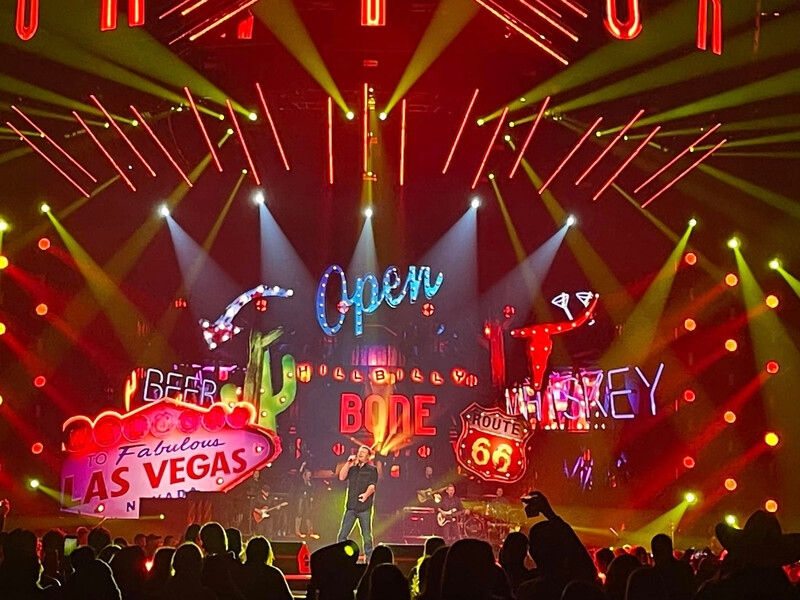

Working with a long list of esteemed lighting designers, most notably his long-time mentor and associate Allen Branton, Peralta has been involved in many high-profile projects as a programmer and LD, including numerous Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremonies, iHeartRadio Music Awards, the Latin Grammy Awards, and Comedy Central Celebrity Roasts. He has also played a key role in Blake Shelton’s groundbreaking “Return To The Honky Tonk Tour,” working with Steve Cohen and Bob Bonniol. Recently, he attracted widespread attention for designing Café Tacvba’s show at the Hollywood Bowl with the LA Philharmonic.

Speaking to us from his Peralta Productions studio in the famed music recording center of Muscle Shoals, he shared insights into the lyrical power of light in music.

When discussing your work for long-time client Café Tacvba on the Hollywood Bowl concert with the LA Philharmonic, you talked about keeping the feeling that the band’s fans expect from their shows while also creating more subtle moods for the orchestral performance. How did you achieve this balance?

“Much of it has to do with tempo. For example, with an electric show the lighting intensity effects would normally be hitting along with the 1/8 notes or 1/16 notes of the music. In an acoustic environment, such as with the LA Philharmonic, I would alter the effect to hit on the ¼ notes of the music, or even on the ½ notes. The “feel” of the song would still be there, but it would be altered to fit the new tempo vibe of the acoustic arrangement. The color palettes of the songs are fairly consistent from the electric show to the acoustic ones.

“Since there are more performers on stage for a show like this, one thing I will normally do is find opportunities in the music to carve out some really high contrast moments to avoid having the stage feel too “flat” in its presence for too long. Hotter back lights with no front key lights, all side light with no front or back lights…no face light whatsoever while the group is silhouetted from our cyclorama are just some of these examples.

Every band, whoever they are, has a unique fan base with its own personality. Do you always think about the fans, not just the bands, when lighting a show?

“I certainly do. I think it’s important to consider both the bands and their fans in order to create a memorable and immersive experience for all involved. I always try to enhance the overall atmosphere, and create a connection between the performers and their audience. It’s definitely a delicate balance to achieve, but something that will hopefully leave a lasting impression on everyone involved.”

So, what kinds of things do you do to connect to fans?

“As we discussed, creating those high contrast moments is really mission critical in keeping the fans engaged throughout the show. Many of my design mentors are great story tellers. They have inspired and shaped a lot of what I like to bring to a stage design. You truly have to be disciplined in your craft and develop a ‘story arc’ that can take the fans on the desired visual journey you are selling.”

At the 2023 iHeart Radio Music Awards show, you worked with Allen Branton’s design to create some very immersive pixel mapped effects to engage TV viewers. At the same time, though, you noted that some of the looks had to be “B-flat” for the live audience at the Dolby Theatre in LA. What sort of looks do you have to sacrifice for the live audience when lighting concerts for television? How do you minimize the damage?

“Ultimately, you’re having to light a show for multiple cameras, perhaps eight, ten, or over 16 cameras with some shows. For most television productions, you have to learn to pick and choose the moments when you can use a small brush, such as fined tuned pixel effects, and when you have to use a bucket of paint for broader strokes in your television lighting. This can mainly be attributed to a couple of key factors, not in any particular order – for example, the amount of time allotted to create the art, and the unfortunate financial parameters that are sometimes attached to these productions. Budgets are usually tight, and you usually won’t have a great deal of time to create a ‘masterpiece.’ The music will also always dictate what it needs. A ballad, for example, may just be a beautiful one look wonder, while a pop medley may require more cueing to enhance the energy of the music. Being well organized and having solid building blocks in your preparation will help you navigate the waters in these high-pressure television production environments.”

This year you also programmed the widely acclaimed Blake Shelton’s “Back To The Honky Tonk” Tour, which received a great deal of attention because of its extensive use of AI. Did AI or any of the other technologies used on that tour affect how you programmed?

“Not necessarily, Steve Cohen and Bob Bonniol had a clear vision of the story arc they wanted to present for the show. This was actually very helpful as it laid out a road map for success on the lighting side. It was clear & concise, and it allowed the lighting story to evolve and become a strong anchor to the visual story.”

On that tour, Bob Bonniol called you “a master of matching and extending the palette with light to engender the feeling of the scenic moments.” Why do you think you’ve had such successful relationships with designers when working as programmer?

“I think that incredible relationships come out of these projects and experiences. You become fully immersed and committed to a project, and you want to see it succeed to its fullest. You always want to surround yourself with people you care about. Inevitably, this will sometimes even shape your decision to take on a project or not. The design team for the Blake tour had full trust in one another – and great results came about just because of that.”

It seems like the relationship between the designer and programmer has changed quite a bit in recent years. As shows have become more elaborate and complex technologically, programmers are assuming a more active/prominent role in their direction. What are your thoughts on that?

“Well, most, if not all will tell you that it definitely takes a village to create these shows. One person cannot do it all. Designers will always want to surround themselves with the very best, and most knowledgeable people that they can. In some instances, when working with a young programmer, the designer may have to give more direction during the process. As the relationship grows with the designer and programmer, there is more trust, and the designer will have more faith in the aesthetics that the programmer develops for him. On top of all this, the technology continually advances, and it’s simply too hard to keep up with all the changes on your own.”

How has the convergence of lighting and video and the creation of immersive 3D environments on stage affected your work?

“I think it has definitely helped us become more creative in our craft. It has also made it more challenging for us. The possibilities are great. This has also heightened the audience’s expectations of what to expect from these productions.”

You’re a drummer, and it shows in the rhythmic quality of your work. Do you think you have to have a musical background or ability to do a good job lighting a concert?

“It certainly helps, but it’s not necessarily required. Lighting design is a multifaceted discipline that involves both technical and artistic elements. These skills can be cultivated and honed through education, experience, and a passion for your craft. In the end, what’s most important is the ability to create a visual experience that enhances the music and resonates with the audience, whether or not one has a strong musical background.”

How do you get inspired at the start of a project?

“When working for a new band, I immerse myself in their musical world and try to wrap my head around their style. I’ll also look at their past productions to see which elements were successful and which can be improved upon. Communication with them and their team is also key. The collaboration can be extremely satisfying during this process.”

Are all your shows timecoded, or do you ever busk?

“It’s a mix. I‘ll always try to be as prepared as I can though. You have to be ready for the unexpected. Busking is an artform in its own right. I don’t necessarily enjoy that part of our craft. I have great respect for my colleagues who live in this world more than I choose to.”

Pyro effects seem to be more common today. Any advice on using them without over-using them?

“Like everything else in show designs, there’s definitely a time and place to use them successfully. And not necessarily just pyro. Special effects in general are great tools that can be used in one’s designs. Pyro, low fog, confetti, lasers, colored smoke, and so forth — all are great tools that can enhance the overall visual experience when used properly.”

You are doing a lot of your own designs. Does your experience as a programmer help you in that regard?

“Yes, one hundred percent. My experience as a programmer has significantly helped me in designing and executing my own projects. Having sat in the programming chair for many years, I’ve been able to surround myself with great designers & have learned a lot from them. The years of experience have offered me a lot of clarity. Being able to see the wide picture of what one is trying to achieve. The technical proficiency and problem-solving skills from the programming side has helped the transition for sure. More importantly, the skill set of keeping calm under the pressure has been a huge plus transitioning to the big chair.”

We’ve always been impressed by the way you change intensity levels in shows, whether as a designer or programmer. It seems like this helps them unfold like a narrative. Any advice on keeping light shows interesting and avoiding repetition?

“Let the music be your guide. The music will always speak to you. It may not necessarily be a huge strobe moment. It could be a simple lighting fade transition that takes three minutes, and creates a huge crescendo, like in Samuel Barber’s epic master piece ‘Adagio for Strings.’”

How did you get started in lighting?

I actually graduated with an audio degree. As a drummer, percussionist…when I realized I wasn’t good enough & wouldn’t be performing on stage, I pursued a career in audio. After graduating, I had student loans to pay back, and couldn’t afford to do the audio internships that were offered. So, I started to take on other production jobs and was relieved to find a creative path in the Lighting world. I did theater in the early ‘90s in South Florida, and then started to learn the television lighting side of my craft in the mid-90s at the Univision Television network in Miami. By 2003, I started Peralta Productions & started to work more independently.”

What do you think you would have done, if you didn’t become a lighting designer/programmer?

“I may have continued to pursue something in the audio world. Or, I may have become a meteorologist…a longtime passion on mine!”

What is the one thing you want people to know about you as a lighting professional?

I’m deeply passionate about my craft. I love what I do. It’s never felt like a job to me. If it ever did, I’d be looking for something new to do.” And…one note of advice, I would give – find balance in your lighting life. Whether is enjoying your family life, going out for a run (a long-time passion of mine), skiing, fishing, anything that’s non lighting related…strike a balance. It truly can be a satisfying career life, when done right.”