Beowulf Boritt – Sculpting Space

Posted on January 5, 2023

The space on a stage is never static in the mind of this Tony Award winning New York scenic designer. It is instead dynamic and alive, something to be molded and transformed over the course of time, with the help of the audience’s imagination (and the work of a lighting designer), to enrich the telling of a play’s narrative.

Beowulf Boritt began developing this sense of sculpting space early in life. His father, noted American Civil War authority and author, Gabor Boritt, would read him stories in the evening when he was a small child. The next day, he would create panoramas of those tales, and in the process, deepen his appreciation of the power of art to shape narratives and define space. He was further inspired by his grandmother, a scenic designer in college, who encouraged him to pursue his artistic ambitions.

That pursuit has taken him to great heights. In addition to winning a Tony Award for his scenic design for “Act One,” he has been nominated for the honor four additional times and won numerous other awards, including the Obie and Drama Desk. Over the course of his still young career, Boritt has worked with many acclaimed directors, such as James Lapine, Kenny Leon, Hal Prince, Susan Stroman, and Jerry Zaks, writer like Stephen Sondheim, and leading lighting designers, such as Ken Billington, Kenneth Posner, and Jeff Crotier.

Boritt’s portfolio of over 20 Broadway shows (and counting!) includes a diverse mix of productions, including Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s “Sondheim on Sondheim”, Steve Martin’s Meteor Shower and “A Bronx Tale,” plus many more. Each show is approached in a way that reflects its own particular character, as well as the vision of its director.

Boritt’s portfolio of over 20 Broadway shows (and counting!) includes a diverse mix of productions, including Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s “Sondheim on Sondheim”, Steve Martin’s Meteor Shower and “A Bronx Tale,” plus many more. Each show is approached in a way that reflects its own particular character, as well as the vision of its director.

In the final analysis, however, Boritt’s core goal is the same for each show: to contribute to the telling of a story by transforming space over time, which is also the title of his recently published book. Taking time from his busy schedule, he discussed the power of this concept with us one afternoon.

Your recently published book about your extraordinary career in theatre is called “Transforming Space Over Time.” Why that title? We’re particularly intrigued by the words “over time” in it

“Interesting question, I chose these words, because they accurately describe what I think my career, and scenic design in general, are all about. As scenic designers, we are not creating static scenery that just resides there on a stage; our work is intended to sculpt space in ways that allow it to change over time as the play progresses. Ideally, this transformation involves more than a changing visual experience. It should also contribute to the unfolding of a story, revealing something about the emotions, insights, conflicts and resolutions that evolve over time. As a scenic designer, I’m there to contribute to the show’s story telling process, just as lighting designers are too.”

You’ve done some beautifully detailed miniature physical models of sets even though you also do 3D printouts. Why do you still do the physical models?

“I’ve always enjoyed making these models. The 3D printouts are excellent tools and give me very precise accuracy in terms of positions and dimensions, but I still want to see the physical models to understand more fully how a decision is going to interact with space and shape it.”

When you look at one of your 3D models after it’s been completed, how does it compare to the image you had in your head when you first envisioned the design. Is something lost in translation as it goes from a thought concept to an actual model?

“Oh yes, most definitely. The honest truth is that it’s almost always a disappointment when you see the actual physical model. I suppose that’s inevitable though, right? When the idea is floating in your head it’s filled with infinite possibilities, which is very exciting. Once it’s turned into a physical entity all those possibilities are lost, except for the one that’s there in your model. It’s not nearly as exciting as the world of infinite possibilities, but you can’t build a set for a Broadway show on concepts.”

Aside from telling stories in your work, you spend careful attention to “engineering” clever scenic pieces, such as the one in “A Bronx Tale,” that went from a bar, to the front steps of an apartment by being turned around. How do you achieve this left brain- right brain balance? Is the detail work just something you just get through to enjoy the creative storytelling?

“No, I actually like the balance between the art and the detail work. Although I was a terrible math student in general, I was good at geometry, which is fortunate given what I do. To me it’s rewarding to figure out the technical puzzles you need to make a design work. There’s a certain satisfaction I get looking at how we can have one thing serve as a kitchen in one scene, and part of a graveyard the next and things of that nature.”

Speaking of “A Bronx Tale,” you’ve talked about how you drew on your experience in the Belmont section of the borough, having worked at the Italian American Theatre in the neighborhood early in your career. Then before you began designing the set you drove up to the Bronx to take photos of the area. But this isn’t always possible, in plays that have no link to an actual physical locale, such as “Flying Over Sunset,” which involves people taking mind altering drugs. How do you get an authentic sense of a place in those cases?

“It’s ideal when you can connect to a place the way I did with The Bronx, and the way I did when I went to Paris to design a set for a play on Edgar Degas. Even though I wasn’t in the city in Degas’ time, I still absorbed a sense of his milieu walking the streets he walked. However, there are always other ways to absorb a milieu. In the case of “Flying Over Sunset,” I never took LSD, and I told James Lapine (the play’s director) that I wasn’t going to start now! He jokingly said, ‘don’t worry, I took enough for both of us.” For that play, I spoke to James and other people who used the drug about that experience. I also read extensively about LSD. This gave me a sense of repeating motifs. In the end though, “Flying Over Sunset” was not about mind altering drugs, the story that we told was about the power of unrestrained imagination.”

You were nominated for a 2022 Tony Award for “Flying Over Sunset.” Can you tell us a little more about how that scenic design evolved?

“The challenge in that play was to find a conceptual location for it, since, as we just discussed, there was no real physical spot on the map where it took place, and also given the nature of its subject. The inspiration came from James, who said ‘think of the inside of someone’s brain on LSD.” That made things fall into place. I created a large volume of space in the set, and endowed it with a lot of physical twists and turns, as I imagined our brains would be on LSD.”

How important is collaboration process between you and lighting designers, and how do you engender its success?

“After the director, the lighting designer is my most important collaborative partner. A good lighting designer can make a bad set look better, and a bad lighting designer can make a good set look worse. Communication is the key to making any collaboration work. I will talk to a lighting designer as soon as possible if I see the set is going to involve something that will present a challenge in terms of lighting, such as a ceiling that is going to impact hang space, or a white background that will affect key lighting. I definitely work with the lighting designer to find solutions to these issues as early as possible in the process.

“I think any good scenic designer should also be open to suggestions from the lighting designer about how lighting can make a scenic piece more dynamic. For example, adding light behind the windows of a building and things of that nature.”

On the subject of lighting, how has LED technology changed the relationship between lighting and scenic design?

“LED has been a game changer in giving us more options, because it allows a great deal of light to come out of a very small space. Also, the substantial improvements in color mixing that we’ve seen in recent years have allowed us to use LED fixtures more widely.”

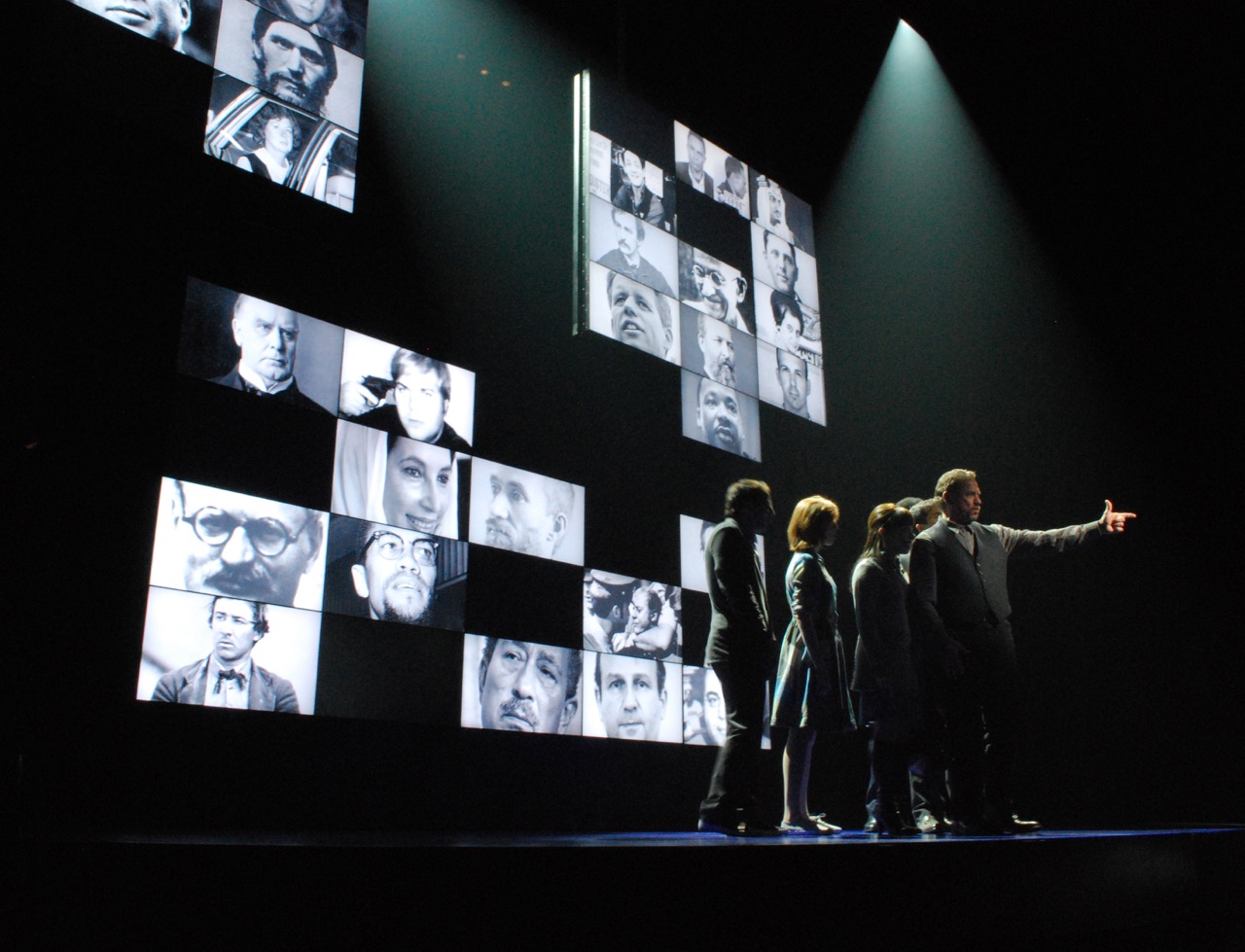

So, what are your thoughts about LED video walls and projection videos in scenic designs?

“You have to be very careful with LED walls. They can overwhelm a stage and make it feel less organic. It’s like having a television set on – eyes get pulled into the screen, which takes away from the role played by the audience’s imagination.

“As for projections, I really see them as part of the scenic design; and I like to be in control of them myself. When I use them, I want them to be more about movement and shadows, like lighting itself, and not about showing objects or places. I think that when you show an object on stage, you should actually have it be there as a real physical entity.”

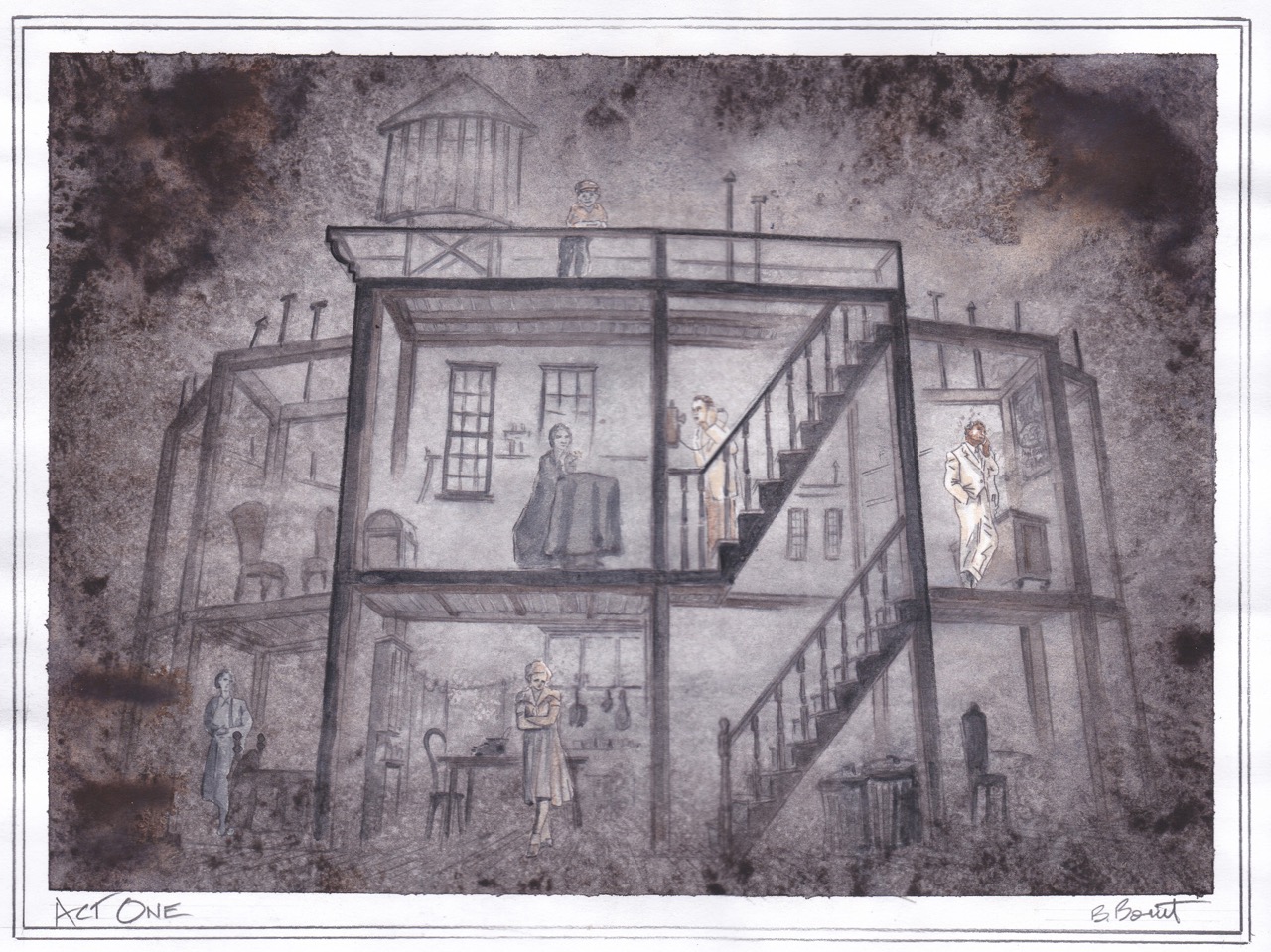

Among your designs that left a lot to the imagination with its open, chaotic look was the one you did for “Act One,” for which you won a Tony Award. Can you tell us a bit about your vision behind that design?

“That one came about as sort of a happy accident. I made a model of a three-story set pretty quickly for James Lapine, the writer and director of the play. As a result, it was kind of raw and unfinished with empty space and a bit chaotic.

“That was very fitting, given that the play was about Moss Hart’s rags to riches story from a poor Bronx boy to an acclaimed writer and director on Broadway. The young people in the play, like all young people, are exciting, but also a little bit messy. Then, of course, the play takes place in New York, which is a beautiful and vibrant city, but also messy and chaotic, with buildings seemingly thrown one on top of the other. So having this chaos build into the set really helped convey the story.”

Lighting designers often tell us that they like to incorporate dark space and shadows into their work to accentuate the light. Does a similar equation apply to the way scenic designers use empty space?

“Yes, absolutely! Theatre is really at its best when it leaves a lot to the imagination. As a set designer you want to leave empty space on the stage to create context and encourage the audience to complete the image. You also want to leave space on the set to give the lighting designer room to create the most desirable light angles possible, and do all of the other things necessary to help light transform space over time, such as suggesting different hours of the day or months of the year, and things of that nature.”

Earlier, you mentioned collaborating with directors. You’ve worked with many of the most prominent. Does the personality of a director influence the way you approach the process of designing for a play?

“Not the personality, but yes, definitely the director’s approach to this art form will affect how I think about a design. Directors all approach their creative work differently, so I will develop my design in a way that is consistent with their vision. We are all contributing to the telling of a story, and a good director will be open to your suggestions. Theatre is a collaborative effort, but in the end the director is the one whose decision is final, so I want to develop ideas in a way that is compatible with that vision from the very start of my creative process. It would make no sense to go down a road that you know will not be aligned with the director’s own vision.

“For example, I’ve worked with Susan Stroman, who has deep roots in dance, so right from the start, I know that I need to leave room on stage for dance when I design sets for her. James Lapin on the other hand, has a graphical arts background, so I will lean toward more off-beat graphical looks with his shows.”

How does the collaboration process progress with directors once you start on a project?

“When we meet initially, I try to learn all I can about the director’ vision for the play. Then, I think about how we can best present that vision visually. Ideally, I like to spend a week, or a month, or even more, thinking about that vision after I talk to a director. Oftentimes, this is the best way to let ideas gel. So, I may be walking down the street thinking of nothing in particular when a really good idea strikes me like a thunderbolt. Of course, that’s ideal, there are times when I’m brought in too late in the process for this to happen.”

You’ve sometimes gone to great lengths to incorporate authenticity into your set designs, doing things like using real trees for “Come From Away.” How important is this authenticity?

“Ideally, I want to be as authentic as possible, but I’m an artist, not an anthropologist. If a scenic element is realistic, but detracts from the telling of the story, we will change it. We are seeking artistic truth, not a factual history.

Speaking of history, you grew up in Gettysburg, a town steeped in historical drama, and your father is indeed a noted American Civil War authority and author. How did this influence you.

“My father is a writer, who was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He helped to inspire my story-telling drive. He would read me stories every night and I would then create little panoramas of them. This was my first taste of sculpting space to tell stories.”

You also said that your grandmother was a big influence in your decision to become a set designer. Can you tell us about her?

“Her name was Anita Marie Wilson Norseen Hooker. She went to Wellesley College where she designed sets for college plays, but was told that was not an appropriate thing for a woman to do in the 1930s. She was extraordinarily creative and had a fine eye. In college she won a national fashion design contest. She painted her whole life and had created award winning landscapes in her New England gardens. She really inspired me to pursue a career in sculpting space.”

Now, you’re working to make careers in design open to more people with the 1/52 project you founded. Can you tell us about that?

“During the pandemic and following the killing of George Floyd there was an awakening that perhaps our society wasn’t as open as we believed it was, at least not for all people. It’s human nature that people tend to feel more comfortable with people who look and act like them. I know, I was aided in my career by other white men. The same opportunities to enter just weren’t there for women and people of color in theatre design. Aside from not being right, this was not healthy from a creative standpoint. I’m convinced that theatre would be much richer, culturally speaking, if shows were created by people with a variety of backgrounds, life experiences and perspectives. So, after consulting with various minority groups, I started the 1/52 project, which asked designers to donate one week’s worth of their 52-week year of earnings to a fund, from which we give grands to early career designers from historically excluded groups to help open the doors to our industry. We just completed our first year and raised one hundred thousand dollars, which allowed us to give out seven grants. It’s a start, and we hope to build on it. Anyone who wants to learn more can visit our website at www.oneeveryfiftytwo.org.”

“That’s a tough one to answer. I hope I’m remembered as someone who created sets that people enjoyed and, most importantly, someone who was a decent human being.”