Ben Dalgleish – Defining Light

Posted on June 14, 2022

Weaving geometric forms into his work in imaginative ways, this New Zealand born and Los Angeles based designer has created compelling shows for clients like Post Malone, Janet Jackson, Keith Urban, Billie Eilish, and others. But though his architecturally inspired looks define space on stage, the vision that powers their creation knows no boundaries.

From his earliest days in Wellington, conjuring up distinctive looks with par cans and strobes, Dalgleish has continuously pushed the limits of his own designs, embracing new technology whenever he could and eagerly venturing forth with untried ideas. He’s actually given a nod to this attitude in his company name “Human Person,” noting that it’s only human to experiment, even if those trials don’t always turn out as planned.

Not surprisingly, Dalgleish incorporates an element of pushing limits within his shows, often masking design elements to reveal them in stages as things progress. We caught up to this busy Knight of Illumination winner and asked him to share his insights into the limitless power of light.

Right off the bat, we have to say that the name of your company Human Person is truly unique! How and why did you come up with it?

“Unique is one way of putting it! It’s a little silly, but kind of came from something I used to say “well they are only a human person”, when someone was trying something out. On the search for a company name it popped back into my head, human person .com was available, and that was that.”

At the start of Keith Urban’s residency show at Caesars Palace, you used a massive spire structure to mask the backline and risers, so at first there was just this beautiful backlighting of the artist. Then, as the show progressed you unveiled an array of impressive design elements. Many of your shows have followed similar trajectories, where you build things up as a show progresses. Why do you follow this approach? Is it accurate to say you view design as a process of unfolding a narrative?

“Myself and Ian Valentine my partner at Human Person have always had a flair for the dramatic opening of a show, and from there, coming up with a little narrative, even if it was just internally for us to follow. I started out doing lighting design with a dozen LED par cans at small clubs in Wellington, New Zealand, I remember even back then I would set myself little challenges “don’t strobe for the first two-thirds of the set” etcetera, just so the show had some kind of development.

“I think now we are just taking that same approach on a much larger scale today — just really thinking about the elements we have and how to layer them to best serve the artist and the show. Thankfully now it’s not just par cans, but automation, musical arrangement, choreography, scenic, video and lighting that we get to play with.”

“I think now we are just taking that same approach on a much larger scale today — just really thinking about the elements we have and how to layer them to best serve the artist and the show. Thankfully now it’s not just par cans, but automation, musical arrangement, choreography, scenic, video and lighting that we get to play with.”

Also, in the Keith Urban project, you changed the position and direction of the spire to give the stage radically different looks at various points in the show. Automation of this kind is much more practical today. Does the growth of automation change the way you look at design? What opportunities does it open for you?

“I wouldn’t say automation changes the way I look at design, so much it affects my focus with the artist, the music and how the design is working within that. However it does open up a lot of opportunities to develop the show in unique ways, creating multiple stages in one. I think the Keith Urban project showed that really well, such as saving some of the more extreme automation positions for some of the slower acoustic songs to allow for maximum impact.”

Your use of video content in the Keith Urban project was also extraordinary, especially how you created 3D effects with it. Yet, your video content never conflicted with the spire or other lighting elements. What’s the key to balancing light and video?

“The key is to have the video content finished on time so lighting has time to program with the content ! Ha-ha, kidding of course – but it’s a very important factor that I’m sure every production struggles with in some way, with render times getting heavier and heavier.

That kind of video content required intense collaboration among a lot of creative people. Any advice on managing collaborations?

“I think most of all recognizing that it is a collaboration, with other creative people that all will have different ways of working. To achieve the best results we often adjust how we operate slightly to best match with the animator or director.”

You’ve become quite well known for incorporating architectural looks into your designs. Do you have a background in architecture?

“No formal background, just a passion and eye for it I guess. I don’t really think about adding architectural looks specifically to any of the productions I work on just for the sake of it, it really has to match the mood and moment.”

What career path would you have followed if you didn’t enter design?

“I was giving being a musician a pretty good shot, playing drums in a number of bands, but really found designing lighting satisfied the creative itch, plus actually paid the bills! “

You’ve designed for a wide variety of artists. Do you have to like an artist’s music personally to create a great design for it, or is it just a matter or appreciating the music in its own right and translating its essence into a physical form?

“No, strangely, I find it easier if I don’t like the artists music going into a project. Every time though I come away from the project a fan, having listened to each song hundreds of times you can’t help but get into it after hearing all the detail in the production and lyrics.”

Are there one or two projects in your career that standout as being the most influential in your development as a designer?

“The first was with a New Zealand band Six60 who challenged me to light their whole show in shades of white + gold. It was a massive challenge right at the start of my career, but up until that point I had just “done lights” – now I was sitting down doing research, planning a show arc and executing it. Fast tracked my development for sure!

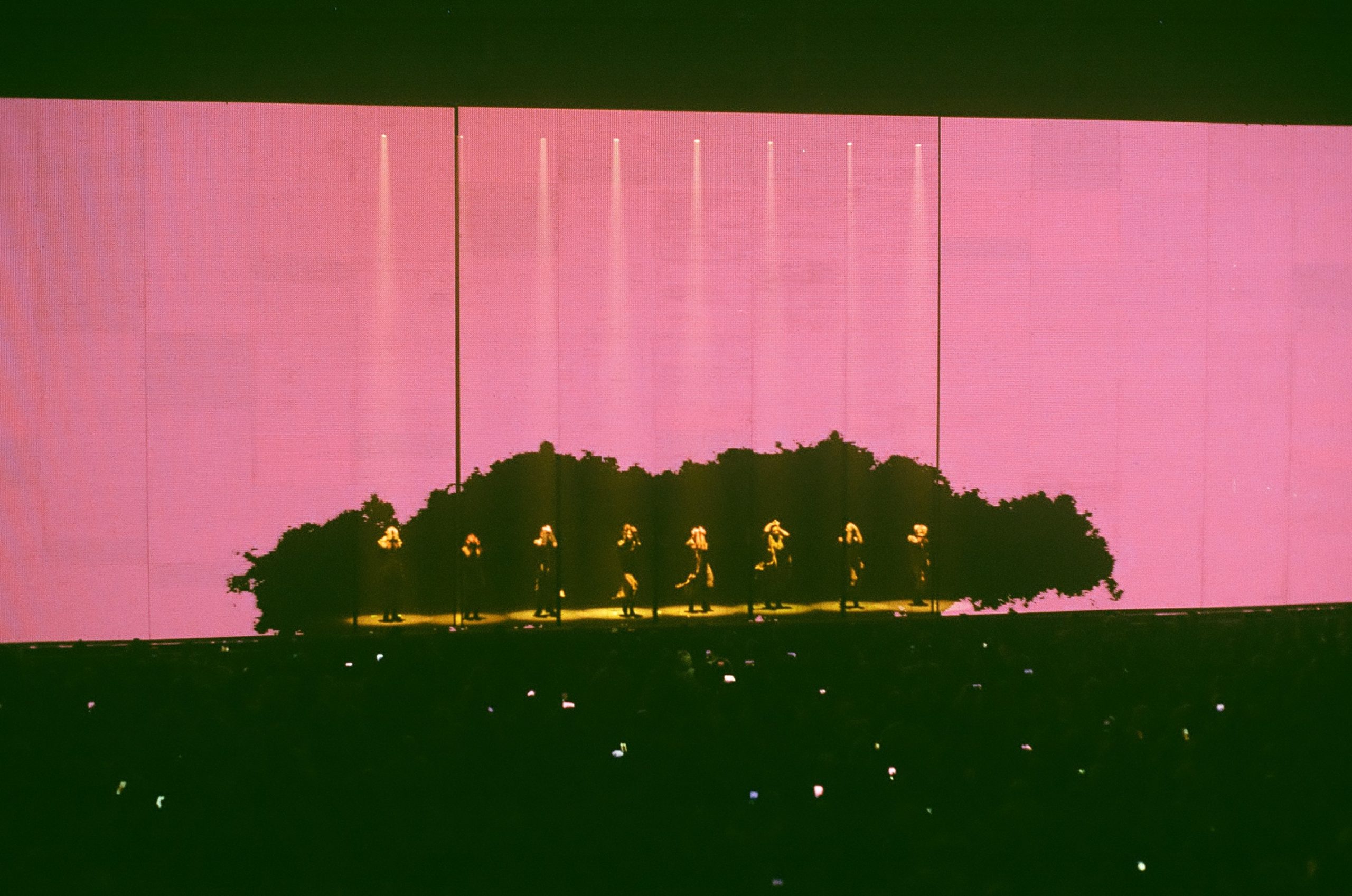

“The second was the Janet Jackson Metamorphosis Las Vegas residency – where I brought in my own animation team to create all the video content and worked closely with the amazing creative director Gil and PM Chris to build a true show with the trappings.”

How do you begin a design? What are the first things you consider when beginning a project?

“I think purposely allowing time to use both sides of the brain independently, then putting it together. I might start by looking at all the logistic requirements, timeline, production budgets etc. or, start by diving into creative concepts, listening to the music up loud and sketching. Both are important, but especially with creative, having time to come up with ideas without thinking of anything logistical is key.”

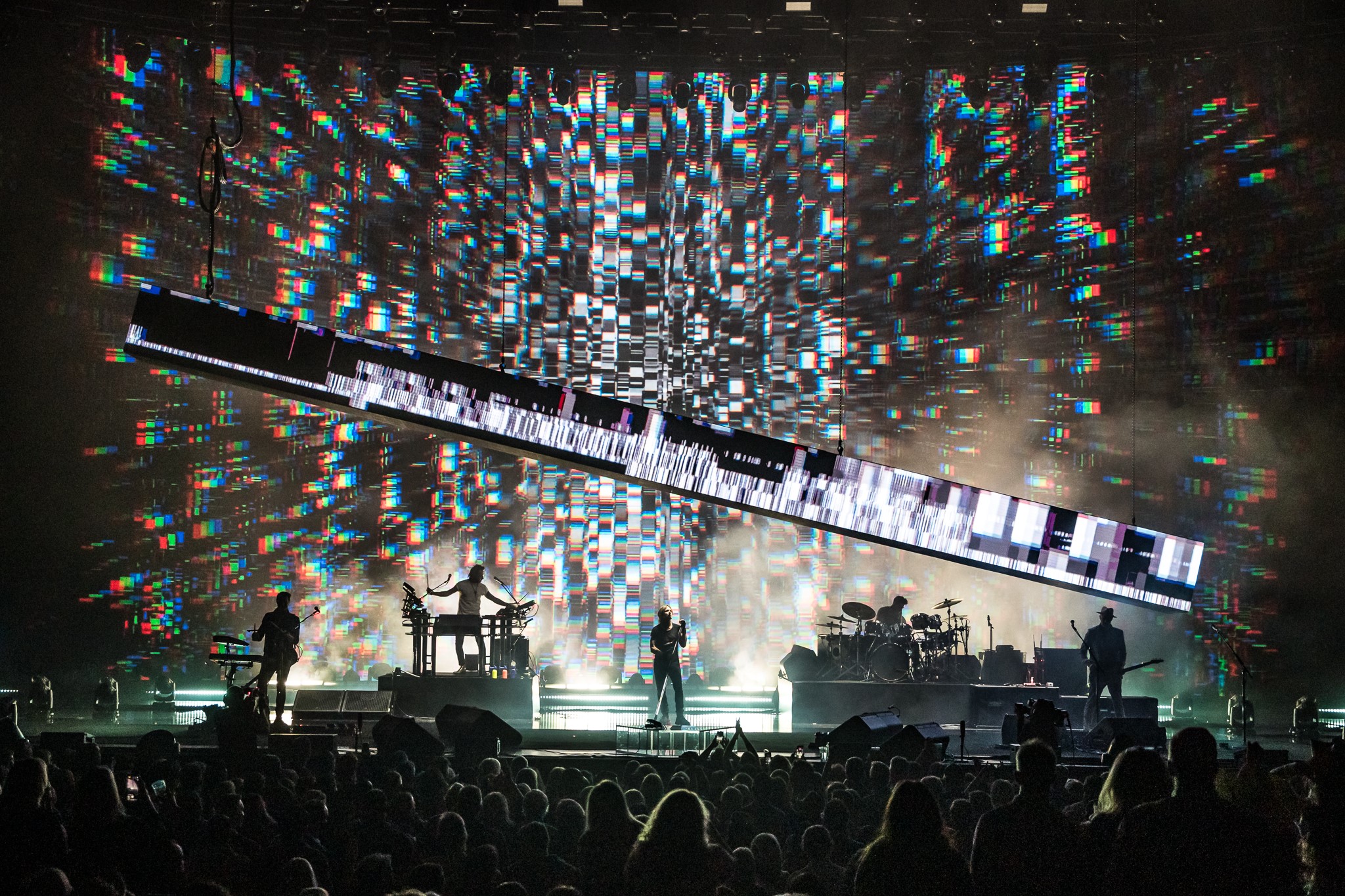

In Post Malone’s Beerbongs and Bentleys World Tour, your design not only incorporated architectural elements, it actually felt as if you converted the stage into an architectural structure with giant walls and overhead grids. Can you tell us a bit about the creative process behind that design?

“With that tour, I had real desire to have the lighting design drive the look and feel of the show, as there was minimal video content, no band, no choreography. For some effects I spent hours trying to figure out what exactly was the right movement to match the moment in the song, creating custom forms, recording wacky timecode on faders, doing everything I could to make it unique and mirror the music exactly.”

Even with some of your smaller shows, such as the one you did for Tove Lo, it seems like you create a sense of architecture. Do you ever do amorphous shows where you just have color washes blending into one another?

“I hope so ! You never want to be known for just one thing. However with the Tove Lo show as it was playing theaters / clubs, there was a real goal to design something physical that would be instantly recognizable as her show.”

You’ve used LED walls as your sole light source at various points in some shows. What is your thinking there? How is the effect different than using a key light or profile to light an artist?

“I think the push and pull of all elements can make a show great, and that goes for front/key light also. Having a perfectly lit artist in white the whole show can get old quick, and breaking that up by using LED panels to light them for a few moments has worked very well for certain shows!”

What is your greatest strength as a designer?

As of right now the greatest strength is the team at Human Person. Having other amazing people to work and collaborate with internally on both the creative and technical side has elevated what I do, while allowing me to be more creative as a designer myself.