Alex Reardon: Taming the Tsunami

Posted on September 26, 2016 Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Before working on the design for the Bad Boy Family Reunion in Brooklyn’s Barclay Center, Alex Reardon sat down with star Sean Puffy Combs to hear what he describes as the hip hop legend’s “tsunami of ideas” regarding the milestone concert. Out of this meeting the London-born lighting and set designer fashioned a show that was brilliant in its scope and intensity, merging video, scenic elements and lighting into a choreographed panorama that captured the essence of the music icon’s vision.

Taking creative tsunamis from artists like Combs, Duran Duran, The Weeknd and many others, harnessing their power, and turning their idea cauldrons into elegantly balanced shows has become something of a trademark for Reardon. His remarkable ability to transform the aspirations of his clients into aesthetically balanced designs has earned him the universal admiration of his peers, not to mention a Parnelli Award nomination.

The owner of Los Angeles-based Wildwood Creative Productions, Reardon is more than a good listener though. Trained in classical music, he has a remarkable ability to blend his designs with the sounds of a diverse range of artists from Demi Lovato to Avicii to John Legend. An avid interest in architecture (his father’s profession) has given his work a seamlessly balanced structural quality, and perhaps led to the addition of “set design” to his portfolio.

It was from his architect father that Reardon learned that any designer has to be “as creative as a fine artist, but within somebody else’s specification.” Judging from his ability to reflect other artists’ vision on stage, it’s a lesson he absorbed very well.

Photo Credit: Steve Jennings

Photo Credit: Steve Jennings

You were trained in classical music; what did you play?

“When I was about 8 or 9, my school did a musical aptitude test and found I had some kind of ear. My mother, being the forward thinking person that she is, realized that it would be prudent for me to take up an instrument that few other kids played, primarily so that I’d be more likely to be able to get a music scholarship to one of those private, Hogwarts-style, English boarding schools. So, rather than the violin or – worse – clarinet, they jammed a viola under my chin. Any other instrument would have been unsuitable as I was the shortest boy in my year and hardly big enough to lug a cello about!”

“Having won a music scholarship to Radley (where I met one of my greatest friends, Flying Pig Systems / WholeHog Founder Nick Archdale), my mother thought to give me a guitar as a present for doing so. The 12-year-old me didn’t understand why. She just said ‘girls like guys that play guitar.’ Again, forward thinking!”

Is there a composer and period of music that you gravitate toward?

“There isn’t really one composer I’d say I gravitate to, but I do find something irresistible in the poignancy of Elgar’s Nimrod, & Albinoni’s Adagio. And of course, who’s not going to love a touch of Mozart. Oddly enough I often listen to classical music stations while designing totally unrelated shows – it clears the mind, and is so different that it doesn’t intrude.”

Does this exposure to classical music influence the end result of your work?

“I suppose in some way it does. There is something classical in all music. As Leonard Cohen wrote in “Hallelujah” – ‘The minor fall, the major lift.’ These concepts are globally recognized as elemental in music theory. So the genre of music really doesn’t matter. ‘Unclassical’ performers still use the backbone of classical music, even if they bend it somewhat.”

We know that you make a distinction between illumination and effect when discussing lighting design. Can you elaborate on that? How do you achieve a balance between the two?

“All lighting design is about that ratio. Sometimes the ratio can change in a single bar, sometimes an entire show is based around the ratio being weighted in favor of one or the other. But to exemplify, a classical opera is all about illumination and barely any effects, whereas an EDM show is all about effects and you might see the DJ once or twice. Even within the ‘illumination’ side, there are subsets of ‘how to illuminate.’ I see illumination as just being able to see the act people have come to see, but it can be from some oblique angle, or in silhouette, it can be barely there – all good to remember when the artist says ‘I hate being lit.’”

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Your recent work on Nicki Minaj and A$AP Rocky was impressive. It seems to us that you very successfully incorporated some grandiose scenic elements into your design in both cases. Have scenic elements become more important to your work? Are they getting bigger?

“I started as a lampy. Then, when Flying Pig came along, I started programming WholeHog Ones, then Twos. Then I moved into the ‘LSD Icon’ world, so my roots are very much in lighting. However, I love architecture and had I actually paid any attention at all at school, I would have loved to work in that field. For me, the move into set design seemed natural. So yes, scenic elements are becoming more important. Are they getting bigger? That depends on the act, the show, the budget, the logistics, etc. I’m as happy designing a set for a theater tour as an arena one.”

When you have a big scenic element on stage does it change the way you design?

“My way of designing a show doesn’t change based on the scale of the scenic. I always start by listening to the client. They can talk about anything really, but without you listening to them, you’re never going to ‘get it,’ and you’ll only end up trying to impose your vision on them, rather than supplying a design that merges your creativity with their sensibilities. It’s important for me to tell you that I never see the designs as ‘my show.’ They are the client’s show, and the best accolade I could ever ask for is that the show be seen as perfect for my client’s act.”

In addition to working on tour for some very big stars like Bob Dylan, The Dixie Chicks, Robin Thicke and others, you’ve done a lot of impressive exhibition work, such as the Titanic Bodies Exhibition. How do the two compare?

“The ‘stars’ of the bodies shows were less animated and far less likely to get grumpy!

But seriously…. This was about illumination, about creating a mood and allowing the visitors to the exhibition the ability to get right in and see the intricacies. Other than that, it’s really fairly similar.”

When designing for a tour, is there one element that you always start with? Do you look at one type of fixture first? Scenic elements first?

“Mostly, I’d say the overall shape of the stage comes first – the form. Is it linear? Is it an organic shape? Then I fold in the function: how many band members, dancers, any gags / reveals? Throughout the process I keep an eye on site lines (no pun intended) and scale. There’s no point designing something that won’t fit!”

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

What do you design in?

“My preliminary concept drawings I do in Cinema 4D, then the tech drawings I do in VW.”

How do you get inspired?

“Inspiration is a funny thing. I get ideas from anything, from the corner of a chair leg, from the shape of a building. Although of late, I seem to find inspiration in very small things; a pen cap, the edge of a cell phone. I’ve got no idea what that’s all about, but it seems to work.”

You’ve talked a lot about balancing the pragmatic i.e. budgetary demands of a job with the aesthetic and logistic demands. During the creative process do you think about all three more or less simultaneously; or do you start with one? For example, will you think of a design that would be ideal and then pare it down because of logistical or financial reasons? Or do you start out with your budget in mind and fit your creative ideas into that paradigm?

“I’d like to say that budget is first and foremost, but that’d be utter rubbish! Of course I aim high. I do start by finding out from the production manager the average stage size. Are we doing theaters / arenas? If it’s theaters, I think a kind of six truck deal. If it’s arenas, eight to twelve trucks. It helps that I use a template ‘arena’ in C4D that keeps me to the average internal dims of most American arenas.”

What are your feelings about LED video walls and projection video? Do you favor one?

“I don’t favor one over the other as they both achieve very different effects. Granted, they both portray content, but the quality of image on a projection screen is so vastly different. The new 7mm screens are gorgeous too. It’s a little like saying ‘do you favor hard edge or soft edge moving lights?’ They both do a very similar job, just in a different way.”

“It’s also always worth asking ‘Is this tour going to summer festivals in Northern Europe?’ because of the associated sunset time problems. It sounds obvious, but (and anecdotally, mentioning no names) I did have one client who told me they wanted to projection map inflatables at Coachella. Everyone in the room thought it a marvelous idea, until I pointed out the proximity of a wind farm. I was expecting everyone to get it and move on, but I was struck by one of those eye popping incredulous moments when I was asked ‘so?’ It’s important to know when NOT to face-palm.”

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

When you design for a tour, do you tweak your work after the tour starts?

“I used to — when I was still touring with the act. These days, I tend to get the great help of marvelous programmers and operators. They are people I can communicate really easily with, and people who get what I’m all about, and who (importantly) I trust implicitly. There are a few people in our tiny little industry that have been, shall we say, less-than-scrupulous in how they get gigs. It always strikes me as remarkably short-sited, as everyone knows everyone.”

Are artists today more aware of lighting and more likely to give you their ideas on what they want?

“Ever since I started, it’s been a case of ‘some do and some don’t.’ Again, anecdotally, sometimes I’ve had artists say they ‘don’t like smoke.’ I saw a thread about this online the other day. My response is ‘Modern haze is to lighting, what a graphic equalizer is to sound.’ Sure, you don’t absolutely HAVE to have it, but…”

“Then I talk them through how haze should be done, how it won’t ruin their larynxes, how it won’t damage backline, etc. I’ve been quite successful with that conversion. I hope any LDs that find themselves in that situation use that phrase ‘It seems to work!’”

You’ve worked for a Who’s Who of artists, is there any artist from the past who you wish you had the chance to design for?

“Ever since I was a young teenager, I’ve been a David Bowie fan. I’m not ashamed to admit I did shed a tear when he passed. It would have been such a wonderful honor to have worked for him. Not only was he of stellar (no pun intended) talent, but also – apparently – one of the nicest gentlemen one could hope to meet.”

What do you regard as the highlights or most memorable moments of your career?

“There have been quite a few – I remember the first time I climbed a truss ladder and walked about on a straight truss. I was surprised at how much it would swing. I remember the first tour I ran the console on. It was as board op for LD Pete Barnes. The act was ‘East 17.’ The console was a Celco Gold triggering an Intellabeam controller. Scottie Sanderson worked with me on that. Fine times indeed!”

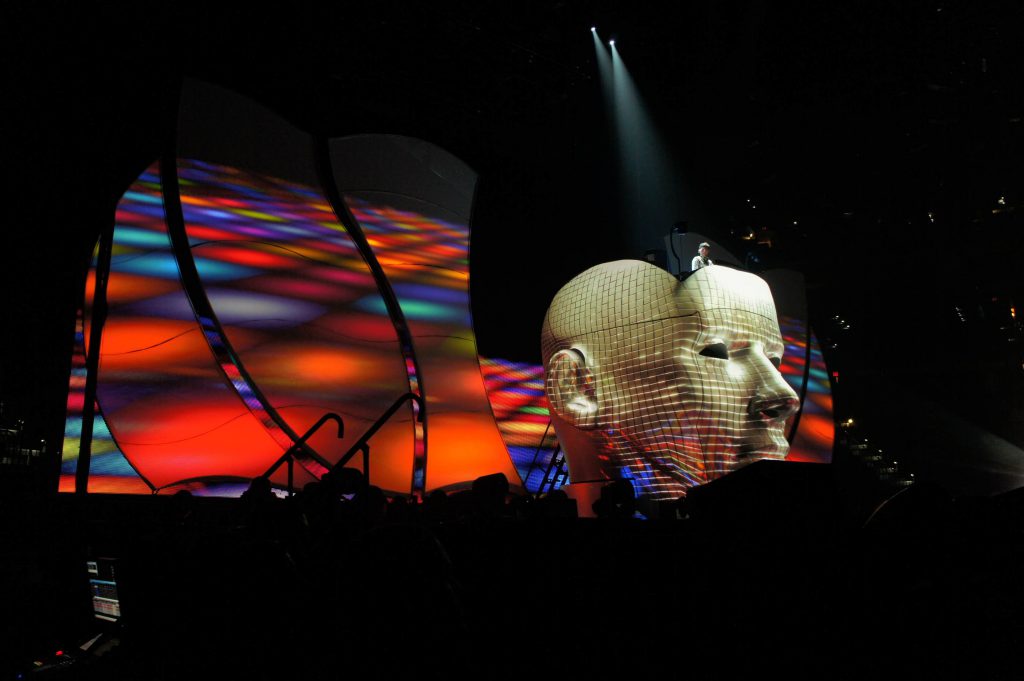

“I remember my first tour of the US with Adam Ant. (Look him up kids, but look back to his early punk days, pre-makeup). The Avicii ‘head’ was quite something. I remember thinking that had I added one more level of design to it, the wheels would have come off. We really created something new there. A wonderful collaboration with a lot of people whose brains really are far bigger than mine – Seth ‘The Genius’ Robinson especially!”

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Who were your biggest influences?

“I’m not sure that I have ‘influences’ in this biz. I enormously respect a lot of people, all of whom are doing incredible work, but I tend to get inspiration from other influences rather that shows I’ve seen.”

Virtually all concerts today are videoed; does this influence the way you design now compared to 20 years ago?

“It depends on what is being shot, and depends on the age and self-image of the artist. As a result; knowledge of how color temperature works on various skin tones, knowing how shadows effect the face, and knowing that hi-def will show everything, is important.”

Do you like to incorporate projection mapping into your designs? What are your thoughts on that?

“Sometimes I do, as with Avicci. The really important thing to remember with projection mapping is that, if you need to classically illuminate your subject, make sure the set designer (if it’s not you), the director, the choreographer, and the artist know to keep some distance from the mapped surface. An omission at the design stage can leave the LD with his head in his hands (or on a spike) if light spill corrupts the projected image.”

If you had to describe the job of a lighting designer to someone who never heard of the profession before what would you say? Also what are the qualities that go into making a good lighting designer?

“Well my sensible answer is: ‘creating a mood, and an atmosphere, through the spectrum of light and shadow.’ My less-sensible answer is: ‘do you work well with others? Even with little to no sleep? Are you able to drop your vision at the drop of a hat, and come up with another idea in seconds? Again, with no sleep? How do you handle unexpected change? Finally, and- most importantly – I would say ‘you do know there’s no glamour in this, don’t you?’”

What do you regard as your greatest strength as a designer?

“Balance. That might sound odd, but I have to balance creativity, pragmatism, and diplomacy. I have to listen very closely to people that don’t speak ‘lighting design’ or ‘set design,’ then find the balance between what they’ve asked for and what is possible.”

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan

Photo Credit: Todd Kaplan