5 Lessons in Light – Jeff Ravitz

Posted on May 5, 2025

This column marks the first in a series of dialogues in which we ask preeminent lighting designers to share five insights they have gained over years of practicing the wonderful art, science, and craft that underpins our industry.

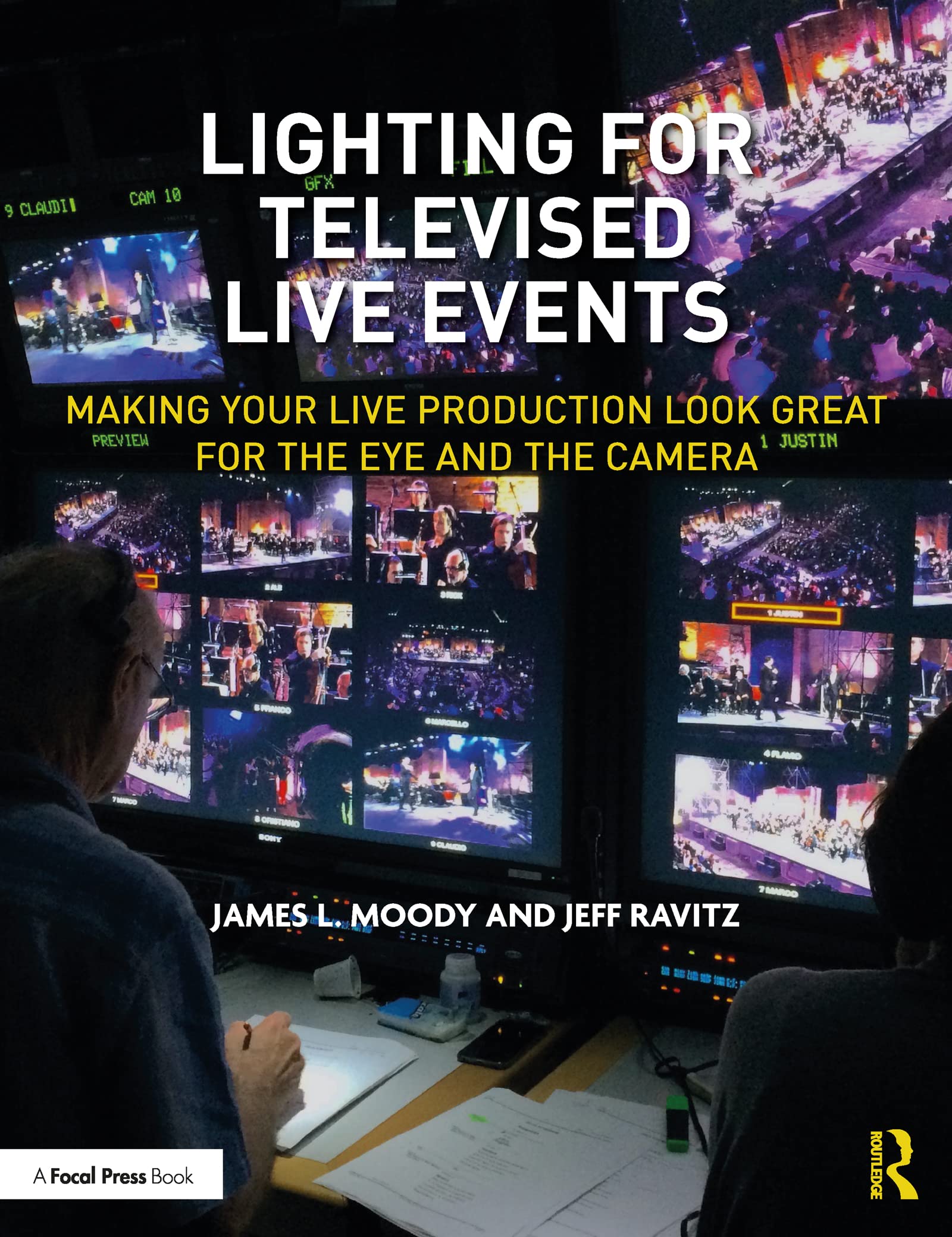

Fittingly, we are inaugurating this series with Jeff Ravitz, a universally esteemed designer and Emmy Award winner, who has not only created some of the most memorable designs for televised events, as well as tours by the likes of Bruce Springsteen, but also has influenced countless other designers through his lectures and writings, including his book Lighting for Televised Live Events.

“I stand on the shoulders of giants,” Isac Newton wrote when explaining his groundbreaking work in physics and mathematics. We are humbled and deeply honored to offer the shoulders of a giant in lighting design to our readers in the hope that it will help them grow and flourish in their careers. Here is Jeff Ravitz in his own words:

——–

Light, we all know, affects us physiologically and emotionally. It was burned into the core instincts of humans and animals, back when the sun told us when to be active and when to sleep, or what season it was. Sunny or cloudy, our moods were altered accordingly.

Light, we all know, affects us physiologically and emotionally. It was burned into the core instincts of humans and animals, back when the sun told us when to be active and when to sleep, or what season it was. Sunny or cloudy, our moods were altered accordingly.

Light is natural—sun, moon, stars, fire, and fireflies.

It’s also an artificial creation, initially invented by humans for practical purposes, until show biz turned light into a vehicle of fun and entertainment, to illuminate, yes, but also to convey mood or spirituality, emulate natural light, imitate weather, shock, delight, reveal and conceal, and to keep the beat.

That’s light. What you do with light is lighting. Even when someone says, “I like the lighting,” they mean what was done with the light.

I was asked to write about what I’ve learned about lighting. I still make discoveries about how to use and manipulate light, as I shift back and forth from live concerts to televised concerts, awards shows, stand-up, talk programs, and events. All very different, and yet they share many of the fundamentals. Early on, I had to train my eye for the needs of a live audience, and later, for how the camera sees. I learned to scan a scene or a monitor, to evaluate and make choices about everything. Once I got the knack of that—and it took a while—it was full steam ahead.

This exercise has really gotten me scouring the archives of my brain to answer: what have I really learned over the years?

- There is a big difference between good lights and good lighting.

I noticed, early in my concert lighting career, that I often saw the emphasis placed on artful and imaginative truss configurations that looked cool but sometimes worked against the best lighting of the performers, scenery, and the general show environment. I like to start with the lights and each one’s purpose in serving the needs of the performance, and then to determine the best angles to reveal everyone and everything. When that process is complete, I can design the lighting system around the principal fixture placements, from highest to lowest priority, and then add more for extra entertainment value. I discovered that once the house lights were out, it was the use of the lights that had more impact than the shape of the lighting system. To me, function leads form. But, if you work it right, you can have both.

- A companion to #1 is: Good illumination does not equal good lighting.

It’s easy to get enough light onto the stage to see. That, by itself, is not enough to make a good-looking picture. I like to light with intention and purpose, and when I forget that approach, I usually get myself into trouble. That means giving lots of thought to every light, how I plan to use it, and exactly where the light needs to come from to create the effect, reveal the person or object, and carefully manage the shadows for maximum impact. This, of course, naturally results in varying degrees of illumination. Sometimes more, other times less. I might be intentionally working to reveal a face or a column only partially. Sometimes, just a kiss of light is all that’s needed to make a statement. Always make a statement.

- Perception: The audience may not know the difference between effective and ineffective lighting, but their brain certainly does.

Here’s one example to illustrate my point. I was lighting a stand-up special and went to visit the show a few weeks before the shoot. The comedian had one lighting request in her contract: a single follow spot. To me, it was quite flat and unpleasant lighting. She still got plenty of laughs, but during the break between shows, I asked the house electrician to add a couple of lekos as backlight. After the show, the comedian’s manager remarked that something was different about the second show and it felt more comfortable to watch. It was just a matter of applying some basic techniques to give her an appearance of dimension, plus a little glow.I see that a lot. The audience doesn’t know what’s not quite right. Perhaps it bugs them on a deeper level they aren’t even conscious of, like glare that you don’t notice ‘til it’s gone. Maybe the band or the backgrounds aren’t lit, or there’s no backlight, and performers look flat and one-dimensional. But when some simple basics are added, the audience eases right into it. It’s a more “comfortable” picture to look at, like the difference between closing one eye for a while and then opening it. Everything looks better, but you might not realize it until you open the other eye.If you ask an audience member what they liked about the lighting for a particular show, they might refer to the most obvious things: effects, flashing, movement and color cues, which is natural. But if you also give them a dose of the “essentials” hidden under all those effects, there’s a good chance they will have an even better visual experience, and not even know why.

- Shadow management: Lighting is as much about creating shadows as it is about eliminating them.

A big epiphany for me happened when I began to do more television lighting for live events. When I see a face filling the entire frame of an IMAG, TV, or computer screen, I become super conscious of how shadows work for or against me. How many shadows do I want? More than one begins to look messy and spoils the visual statement I’m attempting. And where do I want that shadow to fall? Should the face be half or quarter revealed? In the right moments, maybe the face is fully lit, but with a neat jawline shadow on the neck to give the face better dimension. What about eye socket shadows and nose shadows, or purposely weird effect shadows from straight uplight or downlight. The same questions apply to scenic lighting. These are choices to be made. Shadows make a statement, and there’s not an absolute right or wrong. Just the right shadow at the right time. And I want to have control of each one.Once this concept sank in, my non-TV shows became cleaner looking, too, as I noticed the same dynamics also existed for live productions.

- The age-old debate: does lighting support the performance or is it “the performance”?

We’ve struggled with this one, but I am squarely in the “support” camp. Yes, especially in the concert world, the lighting can keep pace with the performance, reinforce the music, and, of course, elevate the experience. Also, there are skilled and talented musicians that present a less physical performance, so the right lighting can lift the energy level, hopefully without distracting from the music. There may be “light shows” that stand alone and need only a music track that accompanies the lighting, like at a dance club or maybe an EDM show. But for a production with live musicians or actors, there is a cooperative relationship between the performance and the production elements, with the performance leading the way and the production helping deliver the message. If the lighting becomes the message, the scale is out of balance.

- Taste and aesthetics change with the cultural times, and so should my lighting.

Just like fashion, architecture, hair style, and food trends, lighting advances forward and evolves—either to match public taste or create it. The moving light generated a newfound expectation for animation and innovative dynamics in stage lighting that we never previously imagined or demanded. New console technology over the years has allowed for increasingly more complex lighting that happens faster, with less effort. The result: new looks, new ideas, new aesthetics, new ways of doing things. What once might have felt overdone or distracting is now the new normal. While I’m always working to match the right style to the right moment, it’s liberating to realize that even newer ideas are just around the corner.This was a more challenging topic than I imagined, and I really had to dig deeply to decide on the five (and a-half) themes I wanted to highlight, despite having had these thoughts in my head for ages. I know this series of articles will open up a host of lessons learned, and I very much look forward to reading what my friends and colleagues add to the conversation.

Jeff Ravitz is an Emmy-winning lighting designer, lecturer and writer, and co-authored the book Lighting for Televised Live Events which attempts to unlock the mysteries of lighting stage productions for the camera.