Mike Grabowski – Metamorphic Light

Posted on March 1, 2022

Reality is not what it seems inside a studio or remote broadcast site. The deep purple background that viewers see on their screens will likely appear blue or pink to the production crew watching live. The bright sunlight that makes the same crew squint on an outdoor set, will seem gently subdued to those tuning in on TV.

This is a bit of visual slight-of-hand, a hustle played on the viewer’s senses. Orchestrating countless variables, letting the viewer see and hear only what the show’s creators want, like a well-seasoned grifter, a broadcast production team transforms the often chaotic world of a set into a crisp, clean, audience-pleasing experience.

Playing a key role in this process is one of the things Mike Grabowski likes best about being a broadcast lighting designer. Only there is nothing secretive or mysterious about the steps he and the other professionals involved take to achieve this impressive metamorphic transformation. It is instead a beautifully balanced mix of precise technology, storytelling, and artistic inspiration – along with a healthy dosage of collaboration among creatives.

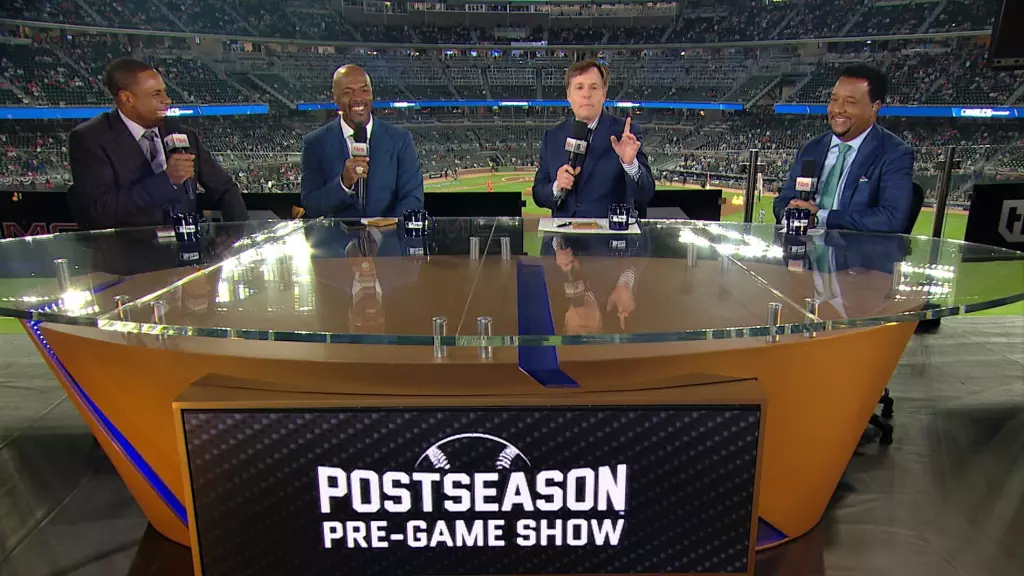

Grabowski, the senior designer at The Lighting Design Group in New York excels at all of the above. During the course of his career, he has lit an impressive list of television programs and events, including outdoor projects like Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve with Ryan Seacrest and the 2021 National Leage Championship Series pre and post-game shows on TBS, as well as studio work, such as the NBC/MSNBC Town Halls, MTV’s TRL, countless reality show reunion specials for Bravo, VH1, and MTV , AMC’s Comic Book Men, Comedy Central’s The God’s Honest Truth, VH1’s Love & Hip Hop Reunions and more.

Grabowski, the senior designer at The Lighting Design Group in New York excels at all of the above. During the course of his career, he has lit an impressive list of television programs and events, including outdoor projects like Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve with Ryan Seacrest and the 2021 National Leage Championship Series pre and post-game shows on TBS, as well as studio work, such as the NBC/MSNBC Town Halls, MTV’s TRL, countless reality show reunion specials for Bravo, VH1, and MTV , AMC’s Comic Book Men, Comedy Central’s The God’s Honest Truth, VH1’s Love & Hip Hop Reunions and more.

As a young man, Grabowski worked for a brief time as a magician and self-described “side show geek.” He is making magic greater than ever today as a lighting designer, and we’re grateful he shared insights into its workings with us.

Last baseball season you lit the broadcast of the National League Championship Series where you had a wide open stadium with its house lights on in many shots. How do you work in that setting and still maintain such realistic key lighting?

“I’m fortunate that I get to work in quite a few “traditional venues” as well as very non- traditional and off-the-beaten-path places. The NLCS broadcast presented a similar challenge to what we face with most location jobs where we parachute in. Unlike with film or episodic work, you have wildly less control over the venue, so you need to embrace it. How do I make this a character in the story we are telling? What are the immutable factors? Stadium lights? Sun? Tremendously low ceilings? Seriously, at Truist Park – The Braves stadium- we ended up at a spot where our HIGHEST bit of ceiling was only 9’2”. And the lowest was about 6’, with obstructions running through. So, when we arrived, we had to blow up the plan a bit! Sometimes, to get it right, you just need rip up the plot, strike all the truss, toss it on stands and buy everyone a whiskey at the end of the day.”

Photo: Dak Dillon

If you were hanging out with someone who lights theatrical productions, would you be able to ‘talk shop’ very much? What are the big differences between broadcast lighting and other kinds of lighting design, such as theatre?

“Is it weird for me to say that I slightly hate talking shop? I’d prefer to ask “What music are you listening to? Find any good restaurants in the last town you were in? What vacation are you trying to plan? I’ll admit it, I’m as bad as anyone, and sometimes go down that rabbit hole, but we are all in those weeds of work so much that it helps balance things out a bit of trying to actively not talk about it for a bit.

“For me, personally, work is a huge part of my life, but I want to see and hear and share other parts of folks’ lives besides just work. Does that make sense? That said, I come from a background in theatre and still love it and carry so many of those lessons with me –and I’m still dear friends with a bunch of theatre, event, architectural LD’s.

“I learned early on in college at SUNY Purchase that to have a concept, a germ of an idea, is essential. I think so many folks associate that with theatre, but I think it translates through all design. What does change are the logistics and mechanical considerations. However, where I may be doing a location job and having IP rated fixtures is super helpful, a theatre designer may not care about that consideration.

“We’re all trying to support a production and facilitate the story being told through our design; most of the time, it’s just the logistical considerations that are a bit different. With my television work, things are often so much faster than theatre. For example, in a show I am doing right now, we had one pre-hang day, two days of set build, one day of focus and set finish, one day of ESU (technical/camera/audio setup and fax) and rehearsal. Then on the next day we shot our first episode. That was five days from empty room to a full on first season game show shooting its first episode. Even for TV that’s a bit aggressive, and often there is a bunch more rehearsal, but still, it’s tremendously compressed compared to weeks of tech in a theatre.”

You mentioned you started in theatre; can you tell us about that?

“I began working professionally at The Arden Theatre in Philly – shout out to Amy and Terry Nolan, Glenn, Terry, Clayton and the whole gang who took me under their wing way back then. Working there, in multiple roles over the years helped give me a wider base and understanding of what it takes for a whole production to come together. But while we can all be a bit of nerds talking through the gear, sometimes it’s fun to talk about the weird and the wild — sometimes it’s just fun to hear their process and show flow.”

Theatrical designers will often say that their lighting is used to help the narrative of a play unfold. Is there a story-telling aspect to broadcast lighting, the way there is for show lighting?

“One hundred percent. It’s supporting that visual narrative. How do you help guide the viewer’s eye? I always reference reunion shows when I talk about this. If you’ve seen a reality show reunion that I’ve done, it’s typically four guests on the left side, four guests on the right and a host in the center. These shows cut to all of the singles to capture the conversation.

“I tend to do a slightly modeled beauty light in these cases, so the upstage side of the guest face is just a couple of shades less bright than the downstage. So, as the show is getting between singles, you now have a sense of the architecture—of where people are seated, not just by the camera shots, but as a result of what I’m doing with light.

“On other jobs, I’m trying to help deliver the emotion of a room, or a location without the TV viewer being there. Do I want it to feel like the viewer is getting an intimate performance just for them, even if there are thousands in the crowd? Well, let’s dim the audience a bit, to make them more shapes than people. Or do we want to help make it feel like the viewer is there in the room with those thousands of other audience members? Then let’s brighten it up and help make them feel like they’re fellow concert goers. It’s obviously a huge collaboration with producing, lighting, video, audio and production design, but it’s all pushing forward on what the germ of a concept is for that show.”

You once said that “the camera is the audience.” What did you mean by that? How is different lighting for the camera than it is lighting for the person watching a program through the camera on a TV screen?

“It means I can get away with a lot of nonsense. Stuff on stands, floor lights, etcetera that are hard or impossible to get away with in live events, but are all fair game in a broadcast. Ultimately, the camera is the only way that whatever I do is going to be presented to viewers, so that has to take priority.

“For a variety of reasons, the color you see with your eye is almost never the same as what a camera sees. So, if we want a show to have a particular shade of purple, I can only minimally care about what it looks like in the room; it may look almost blue or pink in person, but on camera, it is the exact rich, deep purple we wanted.

“Plus, you have to consider where and what is getting shot. Countless times I’ve done jobs in theatres and fly in the electrics, or utilize the side booms for visuals-eye candy. If you look at the last couple of season of “Inside The Actor’s Studio,” I did a bit of an overt nod to this, and we really made it part of the scenery and world. That was a nod to the theatrical, done for television.”

On the subject of cameras, they have changed quite dramatically since you started, particularly with the advent of HD. They’re much faster now. So how does that effect your approach to lighting?

“It’s great, but also a pain at times. For those that aren’t into the lingo, ‘faster’ refers to a cameras light sensitivity, which means you potentially need less light to achieve the same look as a ‘slower’ camera. It’s a double edged sword, in my experience. It’s great that you can get away with softer less bright source, but to do stuff in low light adds layers of complexity.

“Suddenly, a laptop screen or a phone can throw out a meaningful amount of light that impacts the overall picture. You are now potentially having to add ND to fixtures because you are running them at 10-15 percent intensity. Running that low, you don’t have many steps between your level and out. If you have a fixture at 60-percent, you have 59 increments before you hit zero. If you’re at 10-percent, those 9 steps are bigger jumps, proportionally.

“All that said, it also allows for shooting in places and ways that you previously would have a ton of issues shooting. With how quickly cameras and the tech are evolving, keeping up with change is an essential part of being in this industry. I don’t need to know cameras as well as a video engineer, but the more conversant I am in them, the more I can help my design — and help the show hit air in the way we all want it to.”

Today, more concert lighting designers are saying they are making their work camera friendly because so many shows are being recorded for later broadcast or livestreamed. Based on your experience, what advice would you give them?

“Advice? Call me, I’ll pop on over. Ha, It’s just a bit of a pivot of brain space. I came up working MTV, all the way back to the original TRL days, so televised music and performances make sense to me.

“The biggest thing is to think about color temperature. It’s something often overlooked in a lot of applications, but the cleanest and prettiest shows, have color balanced spots and keys. So, pick a color temp for your show and bang in a few more color palettes. Now, if you need to swing a light to hit talent, instead of a spot, or you just need a little extra oomph, it’s all balanced and doesn’t look like a punt.

Photo: Dak Dillon

“Another thing is to familiarize yourself with the cameras. Get familiar with their capabilities, with what they do well, how they exaggerate their colors. Find the video engineer and talk with them…maybe bring them to FOH, pace through some looks and talk through how you want to see it translated. It may mean changing things up a bit—and it may look a little weird in the room, but it will translate better on camera. Finding that balance is hard, but being familiar with these factors and having productive conversations and collaborations is essential. Especially in television, everything is intrinsically tied to other people’s work.”

How has the use of front lighting in broadcast applications changed over the years?

‘I’m not sure it has changed very dramatically but application and use has evolved, if that makes any sense. It all whittles down to making people look like the best version of themselves.

“There has been a willingness to get more cinematic in broadcasts, as a result more often cinema cams and DSLR’s are getting used to shoot content. Shallower depth of field, playing with flares — those are opportunities to help craft the picture, as a LD or even as it drifts into more of a DP type of role. Not everything has to be the soft perfect portraiture of a news broadcast. Because of the sensitivity of cameras and wanting content to look different, there is more willingness to get a bit more dramatic and interesting.

“Additionally, with LED’s, it really means you can dig in and get the colors exactly where you want them, and dialed into a person’s specific skin tones. I’m lucky and have a host and producing team that really trusts me. The show, ‘That’s the God’s Honest Truth’ on Comedy Central is a good example of how things evolve. We did a pretty solid beauty light setup for our host, but to make it a little different, since it’s more of a late night conversational show, we wrapped him with some deep purples, and amber edge light. The rig itself is pretty “standard” for a flattering look, but we got to go with pretty nontraditional colors for something really unique. This is something that we are only able to realize with cameras that can render color well, producers and talent that are willing to experiment, and LED’s that really let you get into minutiae.”

What are the first things you do when you’re given a new project?

“It depends on how it comes to me, but generally it’s a producer calling me about a project. In that case, I will try to dive in with them as much as I can. I don’t necessarily want them to describe what they want out of the lighting . It’s more a matter of ‘give me your concept, your intent for the show.’ Let’s talk at that top, broad level, and then we can drill down to the nitty gritty.

Usually after this, come calls to the production designer, followed by the director. Once that’s done, it’s diving back into things. Because lighting touches and impacts so many of the other disciplines—screens, set, cameras, etc.—a lot of time we become the go between in a lot of aspects, simply because we are a hub of information.

“For me, at that point, I tend to dive into a few sketches. Really just doodles. Quick little postcard sketches with some oil pastels helps me wrap my head around some of the visual language of the show. Maybe a wide shot, maybe a specific “Special Moment”. It helps me land on the picture that I want to help deliver…and then I can engineer that into a plot. That’s when I can shift gears and get into the technical and execution part of things. I will say, it is funny looking at studio television light plots versus theatre plots. TV plots can sometimes look a bunch more chaotic-with sticks and stirrups and grip, there is a lot more overlap, there is a lot more info on a lot of television plots that isn’t there on a more traditional theatre plot. So, it’s detailed chaos, perhaps.”

You’ve done a lot of great designs of very different kinds. Is there one that stands out as having been the most challenging? What did you learn from that project?

“This is one of the harder questions to answer! All of them? None of them? I think on all of my jobs, good, bad or otherwise, the important lesson has been to make sure you have a team you can trust, and has your back. That’s what gets you through those thin moments,and lets you pivot at the drop of a hat.

Photo: Zach Dilgard MTV

“Some jobs are tough just because you can feel a bit creatively tapped out. I remember when I was working on the original run of TRL, we would shoot multiple episodes in a day, as well as a MiTRL for MTV Tr3s. There were days when we did three or four performances, for wildly disparate artists, plus stunts or games that were part of the show. This was in addition to a host of other specific requests from producers or directors. And you know what? Sometimes in those situations, you get tapped out. You just don’t know how to make it fresh or interesting. You can go back to staples that you know work. But to me, you can sometimes see when that’s done – when there is a lack of heart in it. In those instances, Jerry “Subtle” Grant was always my backstop. That dude is underappreciated. He was the programmer for countless LD’s at MTV and has seen it all and then some. Having him there as a backstop, especially for music was invaluable.

“Alternatively, sometimes it’s the location and logistics that’s the challenge. I’ve done the NY standup portions and midnight moment for Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin Eve with Ryan Seacrest for a while now, and that is tough living! A few years ago, it’ was minus 10 degrees at midnight! You need a bulletproof team like I had like Jeremy Domenick and Wolfram Ott as ALD’s, as well as Joey Cartagena, Ryan Philips, Paul Braile and the rest of the Local 1 gang.”

With lighting being capable of creating more realistic colors, faster and smoother color changes and more aesthetically pleasing patterns, are directors more prone to use it to change the mood of a set?

“It’s more about the producing team being on board with that sort of thing as well as the director. So much of the overall “vision” comes from the executive team, but with all of the LED options, you have to balance both extremes.

“Some producers see it as an opportunity to add visual interest and contrast, but also have a visual through-line. Good Morning Football on the NFL Network is a good example of this. We have a ton of LED tape and set electrics built in, but it’s all done purposefully. Larry Hartman of Jack Morton do an amazing job with that. The LED accents are there and allow the room to become absolutely anything, but it’s all very purposeful

“Conversely, it’s something that needs to be managed. Too many times, folks will have an idea that lights or LED’s are a bit of magic? As I always try to remind myself, LED’s and color changing fixtures are not a substitute for a decision. They can help finesse it, but aren’t a replacement. I can’t count the times I’ve heard some variation of ‘the color on the drop/drape wall is fine. If we hate it when we get there, lighting can change it.’”

What led you to choose broadcast lighting? Have you ever lit other types of projects?

“As I mentioned earlier, I started in theatre and opera and really loved it. But, as I moved out of school, it felt so darn slow, at least for me. I enjoyed pouring over the minutiae of a thing to a certain extent, but after a while, it just was tiring.

“So, I bounced around. I worked in shops, as an electrician, and spent a lot of time drafting. I realized it was a skillset that, at the time knowing MiniCAD, hand Drafting, AutoCad and then Vectorworks made me useful in industries outside of entertainment. Heck, for a brief time I did some maritime drafting! But that’s how I stumbled into television lighting. A friend mentioned that The Lighting Design Group needed some freelance drafting done, so I popped in and the amazing team there-Steve Brill, Dennis Size and all the rest, took me in and started showing me the ropes of it. I definitely got thrown into the deep end of the pool pretty quick! But man… the speed of it really was appealing.

“There is also an honesty about television. Coming from theatre, the willingness and openness to talk about money and budgets in such a pretty transparent way was really eye opening, in a positive way. Plus, the artists in this industry are wonderful. It’s a weird island of misfit toys, but I love all of our weirdos and getting to collaborate with them. So much of television is a balance between the art and the technical. This balance and contrast are really a lot of fun, especially with the folks who end up working on this end of things.”

What do you think you would have done if you didn’t become a lighting designer?

“Oh man. I’ve been doing this so long—since High School at Abington Friends School. I had wonderful teachers that sent me down this path, so I don’t know what else I would be qualified to do. I used to work as a magician and sideshow geek, but that’s a rough line of work. Only so much fire and lightbulbs you can eat; only so many nails you can slam in your nose — you know? If you don’t, you’ll just have to trust me on that. Maybe I’d embrace my Philly roots and my love of whiskey and open a whiskey and cheesesteak joint. I used to work a little short order back in the day and can still sling a pretty mean cheesesteak. Pair that with the right whiskey or cocktail, and it’s a good evening out.”

Who were the big influences in your career?

“I try to listen and learn from everyone I meet. Fran Brooks all the way back in High School set me on this path. All of my professors at Purchase-Dave Grill, Dennis Parichy in particular. Steve Brill, Dennis Size, Dan Kelley, Niel Galen all taught me a ton, both on site and by seeing them work. Tom Kenny, especially with music….you don’t need to bang on the lights for every cue. I always dig his sort of brash rigs, that respect the artist. It’s a very particular vibe he creates. But really…I love listening and chatting with everyone. Frequent collaborators like Sarah “Gojijra” Jakubasz always bring a ton to the table. You have to learn something from everyone and everything you see and everyone you work with. Every programmer, gaffer, electrician, assistant and associate. Learn a little. Evolve a bit. Get a little weird.”

How would you like to be remembered as a designer?

“As someone who helped put good vibes and great pictures out there, as a solid friend and collaborator, and someone who could leave you with a laugh and a solid recommendation for a drink or a place to grab a bite, no matter which town you’re talking about. Also, I’d like to be thought of as the guy with a quick smile and a rubber chicken”