Howard Werner: Collaborative Light

Posted on August 7, 2018

Sometimes when interviewing designers for this column, we ask them to describe the most important personality traits needed to succeed in this industry. We never posed that question to this legendary New York designer and principal of Lightswitch during our talk with him, but if we had, we get the feeling that the word “collaboration” in some form or another would have appeared high on his list.

Active collaboration is critical, believes Werner, since no element of a design, be it lighting, media or scenery can flourish unless it fits seamlessly with all others. What is the point of creating an impressive lighting display he asks, if the lights fight the video projections they are meant to complement? Before sitting down to bring their ideas to life, the lighting and media designer must have an understanding of how their efforts will be expected to work together.

This holistic approach has helped Werner succeed as both a lighting and media designer. After earning a BFA from the University of Illinois, he started out in theatre and won an American Theatre Wing Award for lighting. As a media designer, he’s been involved in seminal stage productions like “Dreamgirls,” and “Spider Man: Turn off the Dark.” He’s also done major corporate events and walk-through immersive experiences like the widely acclaimed National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey in Times Square. Werner spoke to us about the power of collaboration in creating unified designs.

You’ve done a great deal of impressive work with media/video design as well as lighting design. Do you approach a project with a different mindset as a media designer then you do when you’re strictly a lighting designer?

“My take on it is this: The picture needs to be thought of as a whole. The media designs that I do are just a part of the overall design just like the lighting, the scenery, the costumes etc. I try very hard to not focus on any one aspect of the design just because my credit on a particular project is limited to lighting or media.”

As a media designer, you’ve worked on Broadway with some of the best theatrical lighting designers like Ken Billington in “Dreamgirls,” and Don Holder in “Spider Man: Turn off the Dark.” What’s the key to successful collaboration between media and lighting designers?

“Yes, I have been fortunate to work with many very talented people. While I am designing the media for a project I try to be a respectful collaborator, but I am not shy about voicing an opinion. Over the years, I have learned to say what I think would be best for the project, and not be embarrassed if the idea is not taken or used. I enjoy working with people who are confident in their opinions. I believe the only opinion that is not valid is the one that is not expressed.”

Your work in Spider Man: Turn off the Dark was widely acclaimed. Looking back, what stands out about that project?

“The design process on that show was probably the most intense that I have ever been a part of. The stakes were high and the show was beyond complicated, everyone on that show was on top of their game. We worked long and hard to make that show the best it could be. In the end, some loved it, while others were disappointed. What stands out in my mind was that show was a vision of a lot of very talented people who worked very hard.”

Does the video element always come first when designing for theatre? Do decide on the video wall or projections first and then determine how to work lighting with them?

“Not always. I’ll use Dreamgirls as an example: Robin Wagner and Robert Longbottom the set designer and the director came up with the concept of a modernized version of the set that Robin designed for the original production that Michael Bennett had created. In a similar minimalist design as Robin remarkable original set design, yet using the tool of video, they wanted to express the journey of The Dreams from the stage to the world of film and TV. The Robin, Bobby, my associates and I worked out the set moves and the looks that were on the LED screens beat by beat. Ken was a part of that concept design process. Using a very early version of D3, we then created a 3D model in my studio before a single light was hung. We basically designed the entire show in my studio to use in rehearsals for choreography, blocking and later in the theater for lighting and all the rest of it.”

Video walls are bright and powerful. When you use them in a theatrical project is there a danger of overpowering everything else or making the show look like a rock concert? If so how do you address this?

“I began doing media in the days of Pani and Pigi projection when we were trying to get the images bright enough to balance with the lighting levels. I read lately that the foot candle reading on a current Broadway musical is some ridiculous number. Yes, the shows are getting bright. In the shows that I do, I’d like to think that we strike a balance that gives the audience what they want. We want to provide the energy level that the show deserves, yet at the same time, we do not want lighting or video to overpower what’s on the stage.”

Because of your background, you’re able to bridge the gap between lighting and media design, but many young designers coming up today seem to specialize in one or the other. Do you think there’s a risk of reaching the point where lighting designers and media designer no longer understand each other’s language and there for find it harder to collaborate?

“If that happens, they should look for other work. Honestly when the lighting designer and the media designer are not working together they should both do something else or find other projects to work on.”

Earlier in your career, you received a great deal of attention, favorable mentions in the New York Times and awards for your work as a theatrical lighting designer. Does anything stand out as your favorite project from this phase of your career?

“Those were the times that I did more theatrical projects and I am proud of those times. No one project stands out but I think that the skills that I developed on those earlier shows have stayed with me.”

Is there a ‘Howard Werner’ style of lighting and/or media design?

“I try to design each project with a style that is warranted by the project itself. Obviously, a product launch requires a different style of design than a play.”

In general terms, how do you get inspired at the start of a project?

“I get inspiration from the script and the score or in the case of a corporate project the product or branding of that corporation.”

Can you tell us how Lightswitch was founded, and why you think it’s become so successful?

“Lightswitch is currently in our 25th year, I have been a principal for 18 years and the people that are Lightswitch are some of my dearest friends. It was founded by John Featherstone and Norm Schwab as a place for like-minded designers and technicians to work together. I think we have been successful largely because we are great friends and we each bring something different to the table. Some of us like myself, have roots in theater, other in music, while others in museum or architecture but despite the varied beginnings we try to bounce ideas between one another and I think we are better for it.”

James Joyce once said, ‘writing is never finished, it’s abandoned.’ Is the same true of lighting and media design? Does the design process reach a point where you feel you’ve taken it as far as you can go, so you end it? Or are there times when you just know what you did is right?

“Is that a trick question? When the audience comes in and the curtain goes up the design is done for that day. In some case you can come back tomorrow and make it better, other times the show is a onetime event so hopefully we get it right.”

If you didn’t become a designer what would you have done?

“You know as I get older, I think about that often. My son is now 17 and we are looking at colleges and I see the world open to him to make of it what he wants. It’s a tough question but honestly, I don’t know.”

What are the two or three projects (successes or disappointments) that you’ve been involved with that most shaped your career?

“The Steppenwolf Theater Company production of The Grapes of Wrath is probably the single most influential project that I worked on. I was the Associate Designer to the amazing Kevin Rigdon. We did that show in four very different venues ending at The Cort Theater in NYC. The show was always evolving and the part that made it so great for me was that we always stayed true to the words. We told the story.

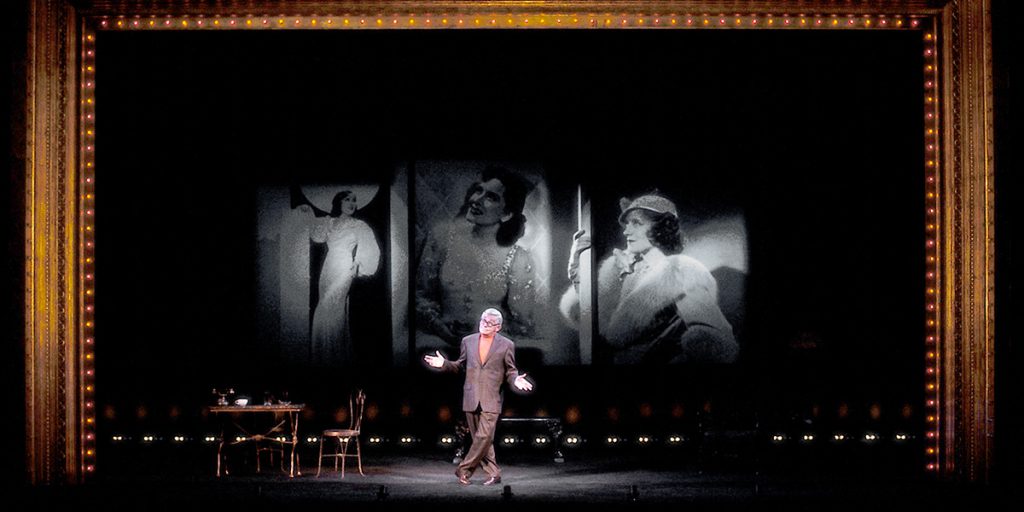

“Dreamgirls was also a high point. We created the world of that show and the media design was a big part of that. I was particularly proud of being a collaborator with Robin Wagner and together recreating a design that was so seminal in 1981.

“I’m gonna go deep in “the way back machine” and pull out a production of Sam Shepard’s Buried Child that I did in college and later was restaged at the Jane Adams Hull House in Chicago. Like Grapes of Wrath this production was totally in your face realism, and we had rain in both shows. Who can’t love a show with rain onstage.”

You’ve done a lot of impressive work for major corporations. Why do you think companies that aren’t in the entertainment field are no placing so much emphasis on using lighting and media at their corporate events?

“Flash and trash is fun. It builds energy and excitement.”

How did you become interested in lighting?

“I began in high school. My school had/has a great program in the arts and that is what I fell into. I played football freshman year and quickly learned that was not for me.”

Before concluding, we can’t let you go without asking about your stunning work on National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey in Times Square. That exhibit offered really kind of a virtual reality experience. How does lighting contribute to the virtual reality experience? Is virtual reality the new frontier in lighting and media?

“I hate to harp on the same thing but the design of Ocean Odyssey is totally about collaboration and all the elements working together, video is the main story telling element but the audio and the lighting support the whole experience. And it has water!!!