Sean Burke: Dividing Light

Posted on February 2, 2016 During our interview with this Irish designer, we often found ourselves talking about things that didn’t directly involve lighting. Strange, when you consider that Burke is one of the most acclaimed LDs of his generation with superstars like Miley Cyrus, Jennifer Lopez and The Cranberries among his clients.

During our interview with this Irish designer, we often found ourselves talking about things that didn’t directly involve lighting. Strange, when you consider that Burke is one of the most acclaimed LDs of his generation with superstars like Miley Cyrus, Jennifer Lopez and The Cranberries among his clients.

Those who know the owner of Holes in the Dark studio, though, would not have been surprised by our wide-ranging conversation. If you were looking for a lighting Renaissance Man, Burke would certainly be on the short list. How else to explain someone whose conversation flows freely from the literature of James Joyce and art of Salvador Dali to 4D design renderings and hanging profile fixtures.

Burke is accustomed to balancing divergent influences in his life and design. As he sees it, the power of an LD’s work comes not merely from illuminating a person or object, but from dividing light and dark spaces. It is the contrast created by this division that gives a design deeper meaning, he maintains. We caught up with Burke to learn more about his insights into dividing light from dark, “shin busters,” his famous clients and a host of other subjects.

The name of your company, Holes in the Dark, is intriguing. Is there a meaning to it?

“The name came from a conversation with an old friend of mine (a mentor and lighting designer, Mr. Mick Hughes) late one night over a few beers. We were discussing what lighting for theatre was all about and the impact it had on people seeing a live performance.

“We were working on a design for a play about Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, the Italian painter. During his life Caravaggio painted with the subjects lit predominately from only one side, which create a very stark contrast between light and dark. Things were hidden in the blackness, subjects lit brightly on one side only, giving the idea that a person or subject had two distinct parts. The light side and the dark side. We all have it in us, this light and dark.

“So we strived to light the show in the manner of the painter. Caravaggio lit one work from the right, a single shaft of light, the rest of his works from the left. So we lit the final scene of the play with one fixture only and from the right. I recall standing on the stage, the room entirely black, and looking at this circular pool of light on the floor, the shaft of light coming at an angle across the stage and literally seeing a hole in the darkness — that circle of light on the floor.”

You’ve been working for Miley Cyrus for some time. You did the lighting for her Wonder World tour and continued on to Gypsy Hearts and Bangerz. Her performance and persona have changed over the years. How has that impacted your lighting design?

“Miley is a lovely person, mad as a brush. She is a real entertainer and she is really passionate about her music and life. I first worked with her when she was a young teenager. The shows were driven by a persona that was known to the public, this character Hannah Montana. The whole life around these shows was not the Miley Cyrus we know now. But as Miley grew away from that persona, the real Miley started to take charge and come to the fore – and so the shows changed from the ‘kiddie pop’ world to a real gritty, flamboyant, larger than life, outspoken young lady who I have grown to love and admire.

She gets on stage and gives it all she’s got every night, and I would like to think the lighting for her shows has grown with her. The show now is very eclectic and portrays Miley the Musician and her great band (that has been with her since the beginning). It also portrays the over the top theatrical performer Miley Cyrus. Basically I try to keep up!”

Does having a long-term relationship with an artist as you do with Miley make it easier to design?

“You know, I’m not sure about that. To light a show you have to understand what it is that the artist wants. That’s something that seems to change with every tour and every band. Every show of a certain ilk these days has a concept. That type of ‘concept show’ has a life and style of its own. Yes, it comes from the artist, but for many it’s an evolving thing. The artists who do concept shows are invariably reinventing themselves every time they go on tour.

“Then on the other hand you have some rock bands that want to get on stage and play.

They are less concerned about how they look than how they sound. This doesn’t make the lighting less of a show with these bands; it’s just a different than it is with a concept show.

“So in answer to your question about whether or not designing is easier when you know and have a long-term relationship with an artist, I guess it depends. Walking into a room and saying, ‘Hey Miley, how’s it going?’ is a lot easier than walking in and saying, ‘Hello Miss Carey, lovely to finally meet you.’ Having that relationship really helps make everyone comfortable; they know you, hopefully trust you (you would not be back in the room otherwise… right?). But then with a concept show artist it’s a whole new ballgame with every new show as far as your design work is concerned.”

You have a very strong style. You also work for high-powered clients. How do you balance the demands between your inspiration and the client’s expectations?

“The first thing is to make the client happy. You always have your own idea of how it should be, but the more important thing is that the client gets what they want. I like to think you get employed as a designer because someone has seen what you do, liked it and trusts you to do a good job for them. You get employed based on your past work. Some people may like your style; others may not. If your clients could do it themselves, they would not need you. I believe you take the client’s expectations and ensure they are met. You add your skill, experience and the inspiration of the concept to come up with the design that fulfills (and hopefully exceeds), the expectations of all involved.”

How involved do your clients get in your design work?

“Some clients like to micromanage the whole process. But they often do this because they genuinely want the best they can get from you in the design process. They have a vision for what the show is about and a clear path in their own mind as how they wish to get there. Others allow you more freedom to make the decisions and produce the design. Often the client will ask for some specific thing; it’s something they have thought about and really want to achieve. It’s putting their stamp on the design. This is something I really welcome.”

Is there any performer from an earlier era that you wish you were around to design for at the time he or she was on stage?

“Marlene Dietrich – what can I say, she was magnificent.”

Your countryman James Joyce once said of writing that it’s never finished, it’s abandoned, meaning you just stop when you’ve taken it as far as you can. How does that work with lighting design? When do you know it’s time to wrap up a project?

“Time. It is all about time. How much time you have to do what you need to do. And as Joyce also said…. ‘Time is, time was, but time shall be no more.’

“A lot of tours these days have too much time. You go into rehearsal and spend weeks, months programming, rehearsing, reprogramming, often only to get back to where your instinct started you off at in the beginning. It is an interesting process – and sometimes a very frustrating one. Also, the more people you have in a room looking at the same thing, the more opinions you receive. The more you analyze something, the more holes you find in it for better or worse. Striving to make it perfect takes time — too much time — and you run around in circles. A friend of mine, who is a brilliant production manager and people manager, once told me not to play my hand too soon because by doing so it creates too much debate.

“So an honest answer for me to give you would be to say that there’s never enough time to reach perfection. You go in prepared, think about where you are going to put the fixtures, and get things right. Then you save yourself and the crew the embarrassment of moving things around. Try your best and then deal with it.”

Do you change designs once a tour has started?

“If I take a tour out myself (which I do a lot because I enjoy the process), there will not be a day that goes by that I will not alter something. It may be a level here, a whole new chase there, better timing on the cue for the cross light on the dancers, or the color of the rear followspot for the solo. Up to the last day — the fine tuning of the show, it’s never over.”

What do you design in?

“Usually a T-shirt and jeans…. Or a robe….. LOL! Ah you mean the other stuff… Well I draw in Vectorworks. I have been using it for years and love it so. Then I export that lot out to a program called Lightconverse, which I also really like and use MS Excel to do the lists and things. When it comes to virtual programming, I’m torn between Lightconverse and ESP Vision. I like them both. Vision is simple to set up, looks good on screen and is easy to edit. Lightconverse is harder to set up, but looks good on screen and comes bundled with my favorite lighting console, hard not to like that right? Both programs are equally good, if not brilliant, and both are equally different. They both produce great results that are realistic and a huge time saver. As we said earlier, it’s all about time…….right?”

What about producing renders for clients?

“Now that’s a different can of worms. So you draw it in VW you know in your head how it’s going to look on stage. I show it to my partner and she asks all the questions…. ‘How does that look, how big is that, what color is it REALLY?’ So then off you go to the world of the ‘final render.’ Export it from VW and put it into Cinema 4D… boom…. There you go. Pretty picture for the client, the screaming fans, the smoke in the air, the massive video wall, the tiny dancers. All lit to perfection! So then my partner looks at it and goes… ‘Ah ok, now I get it!’ And of course you hope the client does too, because it’s a lengthy, costly, time-consuming process to get it right.”

How do you get inspired to design? Listen to music? Walks?

“I listen to my client’s music and try to figure out what the artist is about. What is the show supposed to say, if anything at all. It goes back to what the client wants. It’s the same for the ‘concept’ show or the rock band approach. I have to be inspired by what the artists are trying to say and how they are trying to say it. The trick is to get the vision that is inside their head inside mine too. That can be a scary process with some people!”

We talked about a writer, James Joyce, before — are there any greats from the world of painting that inspire you?

“I love people like Dali. Now there was a head to be inside. Abstract, that’s a good word. I suppose I’m inspired by the artist.”

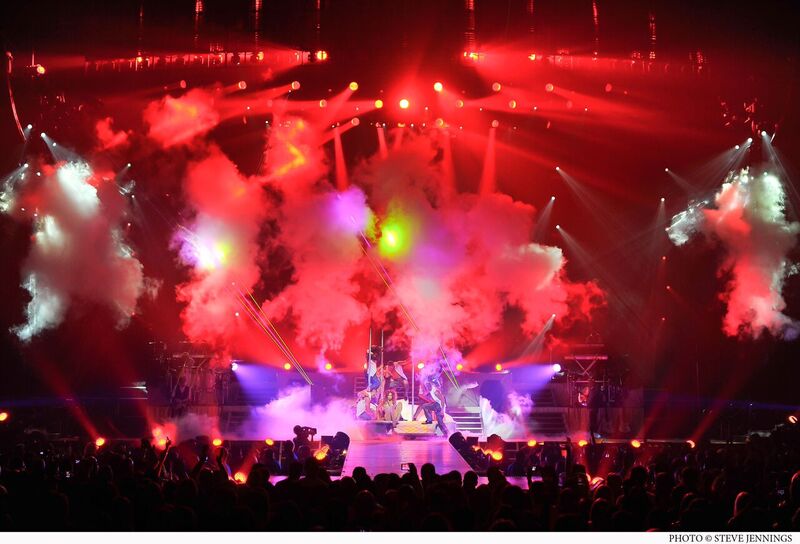

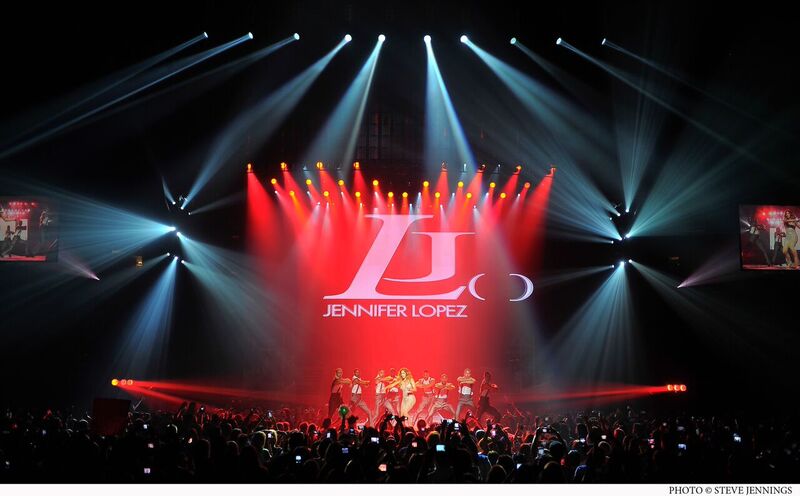

Looking at your own artistic efforts, when you worked on the Jennifer Lopez Dance Again tour, your design covered such a wide stage and there were so many dancers. Can you describe how that was a challenge and tell me how you met it?

“I loved that show by the end. It took a while, it was hard work — but I totally understood ‘the dance show’ by the end of the process. When I was younger I worked in theatre and my dad was the resident lighting designer. We did ballet a few times a year. It took me to do JLo to understand fully what my dad was doing all those years before. This time I had to learn it all over again by myself.”

What are the challenges of lighting a dance-oriented touring concert show?

“The challenge with dance is to see the form of the dancer. Sounds simple enough, right?

It is in a theatre, with a proscenium arch and wing space. A typical rock show has neither of these things. So the challenge is to create a lighting position that does the job, is flexible and DOES NOT create a sightline problem in an arena with steep side and audience close to the side of the stage.”

How do you meet that challenge?

“I approached it like a ballet. We used lots of side light all across the downstage area. We did this by hanging a layered frame of profile fixtures (moving heads) that, once overlapped, would cover the down stage area in a block in three levels. This way we could light the middle of the stage, offstage of the middle and right on the edge of the stage. So every day it was a bit of trim height playing about. I’d sit in the top seat or stand with my friend Art, our rigger, and tweak the truss so the person in the top seat could see the stage. Some days we won the war, other days we lost. And this was where the secret weapon came into play. The floor light, ‘shin busters,’ as my dad would say. Lights on the vertical booms close to the floor became known as shin busters for the obvious reason. Many a dancer has walked into them in the dark with painful results. Our take on it was to have large output wash lights on the floor cross lighting the stage. Invaluable and a great look for other things when not lighting dancers. So between the ‘frames’ and the floor lights, it worked really well.”

With The Cranberries you were the set designer as well as the lighting designer. Which did you do first, set design or lighting design on that project? How do the two influence one another?

“The last design I did for The Cranberries was a run in South America and Southeast Asia.

“As with a lot of tours in these regions, you do not bring set or lighting or PA with you. It is too prohibitive cost-wise for most acts and the promoters. You get equipment locally and you fly the band’s backline in – which the band must have.

“Our challenge with The Cranberries show was to live within this practical necessity, but still produce a show with visual elements that went beyond standard risers and a lighting rig. The guys in the band were adamant we had to have some production value to the show. It was really important to them that the fans had a visually good show. So we came up with a set of soft goods that were compact and could be hung on truss or pipes that would be sourced locally as part of the lighting system. The soft goods could fold up, go in a bag and then go in a hamper taking little or no space. I am indebted to Megan at Sew What for this – absolutely love her! We then added a whole lot of Marshall cabinets to fill the stage. All of this was practical and easy to achieve, yet at the same time it gave us a nice looking stage.

“In many ways our lighting rig for that tour grew around the soft goods – and the position of the soft goods was greatly influenced by where we could position a truss. Overall the lighting and set coexisted and influenced each other massively. I think sometimes that set and lighting or video walls should all come out of one person’s head. You have to think about how they all interact, and when you design like that you do.”

You’ve used massive amounts of moving fixtures in impressive ways, making a powerful statement without overwhelming the artist on stage. It’s also impressive how you create a multi-layered look with your moving fixtures. How do you balance moving fixtures and video walls?

“That’s kind of you to say, thanks. I often think that with modern shows it sometimes becomes all about the video wall. And the audience ends up like they are at home watching the TV. You see all the kids with their phones held up and them watching the show through a 12cm by 5cm screen. They may as well have stayed at home, in my opinion. Sometimes it is just best to turn it off with the walls and fill that slot with moving heads.”

What about set pieces and blinders? What are your thoughts on using but not over-using them in a design?

“Always have blinders. Always. The band will always speak to the audience; the audience will always speak back when you use blinders. The band loves the roar of the crowd, that interaction between the people. All you have to do is let the band see the audience, and the audience will scream back. However, I also advise to be careful when and how you use blinders. They are a big statement in a show or a subtle house light, a glow in the room. You have to pick the right time for that.”

How did you get started as a lighting designer?

“I suppose watching my dad and then a bunch of lucky breaks and meeting the right people. Sounds familiar, does it not? I started in theatre, running about as a child in the biggest theatre in Ireland- what a playground! I love the theatre, that world of make believe and the drama of the human condition. I have always loved the atmosphere created by light. I see it in painters like Caravaggio and Dali and Rubens. They knew how light influences our perception of the world around us. The color and the light and the dark, this plays on our feelings.”

Who were the big influencers in your career?

“My father, my friend Mick Hughes, Ulderico Manani, the opera designer. Dave ‘The Bastard’ Hill, Charlie ‘Cosmo’ Wilson, Patrick Woodruff (mostly because they scared the …….. out of me as a young kid getting started in the rock world, they were Gods.) In art it’s got to be Dali, Caravaggio and Rubens, masters of light. Plus all the musicians I have had the pleasure to work with, the famous and the not-so-famous. I have been lucky in a lot of the people I have met, especially early on in my career. Mick Hughes taught me the importance of placement of fixtures. My dad taught me patience and the need to work hard to achieve anything worthwhile. Whilst working on operas with Ulderico Manani, I learnt about drama and the interaction of the players and the music. Then I met people like Dave Hill and Cosmo Wilson. They taught me to think big and be dramatic with light. All these people showed me the love affair with light, and I’ll be forever grateful to them for that.”

Ireland is a beautiful country; does being there influence your work?

“When I’m home, I’m home. I live in the countryside with magnificent scenery. It’s a really peaceful place to be, I’m very fortunate. I am also fortunate to have a studio full of all my toys in a setting that’s relaxed and beautiful. It gives me the space to think and plan and to work at any time of the day or night I choose without restrictions. Yes, I would say being here influences me a lot.”

How would you like to be remembered as a designer?

“Now there is a good question! I remember as a teenager reading reviews of shows my dad designed. I’d get annoyed that they did not go on at length about the lighting and how great it was. My dad would ask me what it said (he never read the reviews). I would tell him, and he would smile. He would ask me if they said the lighting was bad, I would say, ‘No, they did not.’ He would ask if they said that people were in the dark and could not be seen. Again I’d say, ‘No, they did not.’ He’d just smile and say, ‘Well if they did not mention the lighting as being bad, then it must be good.’ I’d like to be remembered for not being bad.”